Twenty-three years ago, I stumbled home after doing a comedy gig and found myself lying semi-comatose on a sofa watching The Jerry Springer Show on ITV2. I remember six people were hurling abuse at each other. The drama was ridiculously overblown and I couldn’t understand a word they were saying. It struck me – this is like an opera. I remember the exact moment because I decided then and there that I would make this into a show. Not out of some desire to create a searing social satire on the sordid underbelly of the American Dream, but because the bleeping out of the profanity really annoyed me and I thought it would be funny to hear all the swearing sung in beautiful harmony. I got writing.

I had form in this. I was part of a comedy club called Cluub Zarathustra with Stewart Lee, the Mighty Boosh, Simon Munnery and Loré Lixenberg. Whenever our crowds got boisterous, we would wheel out my great friend Lixenberg – a mezzo-soprano also known as The Opera Device – and there would be a war of insults between the London comedy audience and The Opera Device, who sang her insults at full throttle. When I say insults – they were truly vile. But the crowd used to go wild for it. There was something about the operatic sound that diminished the violence of the words, making them all funny and, very bizarrely, life-affirming.

A few months later I called Tom Morris at Battersea Arts Centre. He let me have a 50-seat room for a few nights where I played piano and also Jerry, joined by three singers who performed some early numbers. It went ridiculously well. More dates were scheduled and it quickly snowballed. I wrote a one-act version, then called Stewart Lee to direct and co-write a two-act version. This was my big shot: the breakthrough gig you dream of in showbusiness. I couldn’t believe my luck.

BUT.

I didn’t have the rights. I had never contacted Jerry nor the TV company who made the show.

I knew this was potentially problematic but I had a hunch that Jerry – formerly a politician who was passionate about civil rights, education and the anti-war movement – wouldn’t stop the show. This was an incredibly naive position to take, and I shudder when I think back on it. Jerry could have crushed the show in a heartbeat. He didn’t.

However, the TV company weren’t quite so compliant. They sent a letter that stated they “reserved the right to litigate”. The merest whiff of a legal threat is usually enough to stop a show and put off potential investors. “Why do we need to tell potential investors?” I howled at the world and my agent. “If you don’t, it’s fraud,” he replied. The show was already scheduled for the Edinburgh festival and my feeling was to press on and hope for the best.

Out of the blue, Jerry decided to come to Edinburgh and watch the show. He planned to make a discreet entrance just before the curtain went up and come to his own decision about the production. Everything was riding on it. Well, forget about the discreet entrance. Jerry walked in, an audience member spotted him, and instantly began chanting: “JERRY! JERRY!” The crowd caught on and joined in. It was electric. He was charmed. It was the fringe and he was a global superstar. We were in the clear.

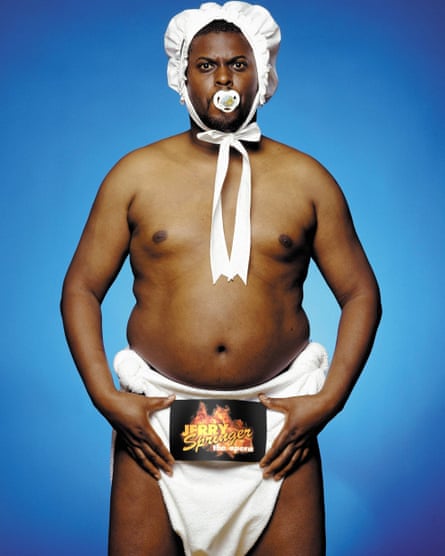

The next time I saw him was on the penultimate preview in London’s West End, the show having transferred. We had done a major rewrite and Jerry Springer: The Opera was now storming it. (Spoiler alert!) God, who appears in the final act, had a new number: It Ain’t Easy Being Me. The reprise of Talk to the Hand had been tweaked to Talk to the Ass (genius!). The whole apology plot was working very well: basically, all our love cheats and cheated-ons were after an apology but no one was saying sorry. Solve that, Jerry! Meanwhile, Baby Jane, the nappy-wearing dude’s secret fetish companion, had a whole raft of moving mini ballads about regret that were landing very well.

Jerry had flown in to do some press for us and the Ivy restaurant was booked for a post-show jolly and we were hoping for some LOLs and some affirmation. But Jerry was not happy. He demanded we change two lines.

The first was a matter of fact: prior to global fame, Jerry was embarking on a political career. Catastrophe struck when he was discovered to have paid a sex worker with a cheque and had been rumbled by his political adversaries. In the show, we had Jerry saying: “The next day it was all over.” In the Ivy, he was at pains to point out that, far from destroying his political career, three years later he was elected mayor of Cincinnati, “the third largest city in Ohio”. So we changed it, already grieving for one less joke in the show.

The second line he wanted to change was much more revealing: in the second half of the show, Jerry is dragged down to hell and forced by the devil to reconcile the irreconcilable forces of good and evil. The price of failing in this impossible task? An eternity in hell being “fucked up the ass with barbed wire”. The reward for succeeding in this impossible task: not getting “fucked up the ass with barbed wire”.

Jerry tries to sort out the divine, dysfunctional family – God, Jesus and the devil – to the worst of his abilities. It’s a lose-lose situation for the host. He is out of his comfort zone and howls in anguish: “I don’t solve problems – I just televise them!” So, on the edge of an eternity of hellfire and rectal trauma, he gives up. Yet his speech of despair actually solves the situation, which basically says there is no solution, you’re never going to get what you want, you’re never going to be truly reconciled.

“Don’t you get it?” our Jerry says. “It’s the human condition we’re talking about. Nothing is wrong and nothing is right and everything that lives is holy.” This really freaked the real Jerry out. “I would not say that,” he said. “Nothing is wrong and nothing is right? The holocaust was wrong.”

So I found myself arguing with a man who was the son of refugees fleeing the Nazis. My only argument was how high the stakes were for the Jerry in the opera. He sighed and let it go, but I could see he was deeply troubled. The opening night in the West End was a huge success. Jerry took a bow and was incredibly gracious.

Last week, the day after he died, I read the script again and was struck by how much we put the character Jerry through in our show. The outcome is dire for him. He is accidentally shot by a nappy-wearing fetishist aiming at the KKK. In his dying speech he laments the road not taken and has a heartbreaking line: “History defines us by what we do and what we choose not to do.” Don’t get me wrong, it’s a great role – but we really stuck the boot in. There is so much in that script that he could have justifiably asked us to remove. Yet, in the end, we only had to change one line.

As a result of his generosity and humility, thousands of people have been employed to do the show across the world. Many, many more have been entertained. And a few have walked out.

Thank you, Jerry Springer. You took care of us.