Ivan Bera, 24, has always loved the feeling of being naked. He says that when he was about 17, he “ decided to try it in public”, with his then girlfriend. Since then, “I have been very busy with the associations in Catalonia,” he tells me. The Catalan naturist-nudist scene is rich, decades-old and organised. Bera is a member of Joves Naturistes, which is for 18- to 35-year-olds; last week the all-ages Naturist-Nudist Federation of Catalonia made a public appeal for tourists wearing swimsuits to stay away from their beaches.

“Legally, we can practise it everywhere: there is no law against nudism in Spain,” Bera says. “But most naturists prefer to practise it in secluded areas with a tradition of it. Those areas are being invaded, mostly in the summer months, by tourists who not only wear swimsuits, but also have a very disrespectful manner to nudists. We feel displaced in our own spaces and we fear losing them.”

For many naturists, the presence of people wearing bikinis is enough to alter the beach for the worse, although Bera says he doesn’t mind having clothed people around. But the behaviour isn’t great – “there are some people who harass nudists, and there are voyeuristic activities and suchlike” – and the insensitivity extends to the natural environment. “In general terms, people who are disrespectful to nudism are disrespectful to nature, and they pollute the area in all kinds of ways.”

It is especially galling because the traditionally nudist beaches are chosen for their seclusion, which often coincides with picture-postcard beauty. So visitors come for the postcard (for younger readers: the Instagram backdrop), and in so doing, turn the beach from three dimensions – a place with history, community and a counter-culture – to two.

The public appeal for tourists in swimsuits to stay away caught the world’s attention. It animated a question playing out in beauty spots and heritage sites all over the world: when tourists flock to a place, do they change its character, wipe out its idiosyncrasies, without even noticing what those idiosyncrasies are? Is there an impact on the residents more important than a boost to ice-cream sales? Can you commodify beauty without tainting it? When does tourism become overtourism?

In the 20 years running up to Covid, international tourism doubled, to 2.4 billion arrivals in 2019. Overall, tourism last year was at 63% of its pre-Covid levels. Every place has its own post-Covid recovery story: Thailand has taken a while and is, at a state level at least, very welcoming to visitors; France has yet to see the same numbers of Chinese and Japanese visitors as before; in Paris – the most popular destination in the world – numbers this year are expected to be almost exactly as they were four years ago, 38.5 million. But people increasingly don’t want a bounce back. Tourist transport accounts for 5% of global emissions, and people are flying into the heatwaves those create. It is all a bit on the nose.

“I think it really helps to think of travelling as a kind of consumption,” says Frederik Fischer, CEO and founder of the social enterprise Neulandia, which connects creative digital workers to rural communities in Germany. “If you only consume another country, or you only consume a city, I’m not sure you’re really doing a benefit to the people and the place.”

Every location has a different challenge with tourists. On Catalan beaches, it may be that they are wearing too many clothes; in Barcelona, there are simply too many people. Whether that turns the entire place into a giant hotel (9.5 million people stayed in Barcelona’s hotels in 2019, a fivefold increase on 1990) or a human traffic-jam (one-way walking systems have been introduced in Barcelona’s city centre), it is impossible to imagine that being a pleasant, livable experience for the host citizens.

In Dubrovnik, tourists are just too annoying. The story went around this summer that wheelie suitcases had been banned from the cobbled old town, an interdiction with quite a substantial fine (€265). In fact, it was just a video suggesting that if people would only pick up their bags, that would be a lot less grating. All the pleas in Croatia’s Respect the City campaign are modest – please don’t fool around on our statuary, or walk around shirtless – but you can hear the quiet desperation you might predict, when a city of 41,000 people greets 1.5 million tourists a year.

Jon Henley, the Guardian’s Europe correspondent, based in Paris, says there is a similar story to Dubrovnik in places such as Prague and Budapest: “Wherever you’ve got a medieval city centre, those become unbearable.” Paris, with its wide boulevards and relatively large city centre, suffers less; when the French tourism minister, Olivia Grégoire, announced a strategy to prevent overtourism earlier this year, her focus was on sites such as Mont-Saint-Michel abbey in Normandy and the Channel beach Étretat, which aren’t large enough for everyone who wants to see them. In the capital, at peak tourist season, all the Parisians, including many in hospitality and retail, are away. “I quite like it in August in Paris for precisely that reason,” Henley says. “Confused-looking tourists wondering why everything’s shut.” If Paris is very tolerant of tourists, Saint-Tropez is getting close to its hard limit on the ones who don’t tip properly.

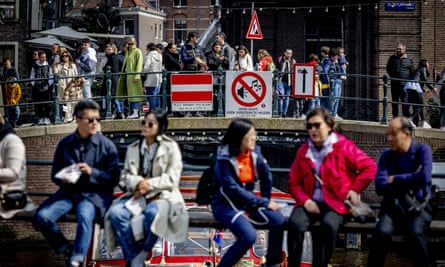

Amsterdam is at the vanguard of the stay-away movement. The city council decided this summer to close the cruise ship terminal in the city centre, specifically citing its sustainability goals. But there is always a subtext, which is often the text, with Dutch imprecations about tourism, which is that people (especially British people) go there specifically to behave like animals. There possibly isn’t a city in the world, medieval or not, that could cope with a visit from a group of Britons who had gone there specifically to get off their heads for 72 hours without stopping. An online campaign launched in the spring, with ads triggered whenever anyone in the UK entered “stag party Amsterdam” or “pub crawl Amsterdam” into a search engine, warned people of the possible consequences – fines, arrests, hospitalisation, making life completely miserable for residents – of hedonistic frenzy. The deputy mayor for economic affairs, Sofyan Mbarki, released a statement at the time: “Visitors are still welcome, but not if they misbehave and cause nuisance. As a city, we are saying: we’d rather not have this, so stay away.”

Other cities can increasingly relate to this. A video did the rounds this week in which a woman walks across the Trevi fountain in Rome to fill her water bottle. In June, a guy was filmed carving his and his girlfriend’s names into the Colosseum. Before you even consider the destinations that people go to specifically to behave badly – Aiya Napa, Amsterdam, Edinburgh, Ghent (the Belgian city is considering banning stag party-friendly beer bikes) – there is always this problem that, as Cornish business owner Mati Ringrose says: “When you go on holiday, it’s not your place, it’s not your community, so you act completely differently, and out of character.” It cannot go unremarked that British tourists are notorious for this. The streets of “Europe’s latest booze hotspot”, Split, in Croatia, are festooned with signs in English warning of fines for public drinking, vomiting and urinating. One girl complained to a reporter this week that the fines were unfair, as she was quite likely to vomit, having had too many “anus burners” (shots of tequila, orange juice and tabasco).

Then there are digital nomads, itinerant workers who, every month or two, move between beauty spots in locations such as Bali, Mexico City, Lisbon, Chiang Mai in Thailand and Medellín in Colombia. These people would style themselves as the opposite of tourists, although as Dave Cook, an anthropologist at University College London, says: “I’d speak to the Chiang Mai coffee shop owner, and they’d say: ‘they’re in a coffee shop and they’re speaking English, so as far as we’re concerned, they’re just tourists.’” Before the pandemic, Cook says, lifestyle migration was a very niche phenomenon, which would include expats but was more of a counter-cultural movement, people specifically rejecting the worker-bee ethic of life in an office. Since Covid, there have been more strands: the freelance knowledge worker, the digital nomad business owner and the salaried digital nomad, which was more or less unheard of pre-pandemic. “Digital nomads talk about ‘dating’ locations: they’re geographically polyamorous,” Cook says. “Resentment can creep in, but what happens in reality is digital nomads might fall in love, but the locals have an intuitive understanding that they’re going to be left.”

What people often object to about visitors, whether they are tourists, expats, retirees or digital nomads, is what they do to property prices. Lisbon is the prime example of a city altered beyond recognition, to many people’s eyes denatured by an influx of people who could just afford higher rents. Michael Oliveira Salac, who is half-British, half-Portuguese and splits his time between London and the Algarve, says it was a combination of tourists and nomadic financial technology workers, who, between creating Airbnb demand and being able to afford much higher long-term rents, forced Lisbon residents out of the city. The minimum wage in Portugal is €760 (£650) a month. It is not possible to compete with an influx of people paying €1,000 a month for a two-bed and laughing about how cheap that is. That creates a cascade effect, Oliveira Salac says. “The main avenue, where there used to be old multibrand boutiques, now Gucci has come in, Prada has come in, so that’s shot the rents up.” The newcomers “want sushi, they want Thai food, they want vegan. The old lot can’t cater to that, so they’ve shut down. Lisbon has lost its soul.” And that picture has played out in Porto, even in some towns in the Algarve: Portugal sits on this axis, where it is comparatively cheap, very beautiful and in the right time zone for a lot of nomads, which from a resident’s perspective is a curse, like sitting on a fault line.

Venice is probably ground zero of the overtoured effect; tourists and residents have hit bed-for-bed parity, which makes normal life in the service of anything other than a tourist unviable. It creates a theme-park effect, to which even Rome – home to the most melodramatic monuments – hasn’t succumbed. In Rome, you can still at least glimpse the life underneath the day trip; in Venice, despite a recent clampdown on city-dwarfing cruise ships, Unesco recently threatened to “blacklist” the city as a world heritage site, citing Italy’s failure to protect it from mass tourism and the climate crisis.

You have to wonder whether it is worth it. Ringrose, who runs a shop in Redruth in Cornwall, isn’t technically homeless because she lives in a van with her seven-month-old child, but she says even parking charges have skyrocketed. “I have so many friends in emergency housing, it’s insane,” she says. In the summer, Cornish resort towns such as St Ives are so crowded that Ringrose has a disabled friend who has to move out because she can’t get down the street. Then, in the winter, she says: “There are whole towns that you go in and there’s no lights on half the year. There’s nothing open. There are no pubs there. Whole swathes of what used to be communities are shut down. It massively affects the mentality of the county.”

Redruth is relatively untouched by tourism because it is not coastal, and “it’s a really deprived area,” Ringrose says, “but it’s not deprived of community. Redruth is ridiculously rich in nice people, because it’s not a tourist town.” Ringrose tells me about a beach in Polzeath with a fence in the middle that someone built to stop people walking along the bottom of their garden. She tells me about the woman at a car boot sale who bought a jumper off her for a tenner, and asked her to split a £50 note. “I have never been given a 50 in a car boot, ever.” At the planning level, at the level of society, every desirable place on earth will have a variant of the Cornish question: if tourism brings in 12% of its income, yet takes up almost all of its housing, so that the lives of the residents don’t function any more, how can that be OK. At the level of the tourist or the nomad, the proposition is as simple, but an easier fix: look around – if everyone else is naked, either get naked or go away.