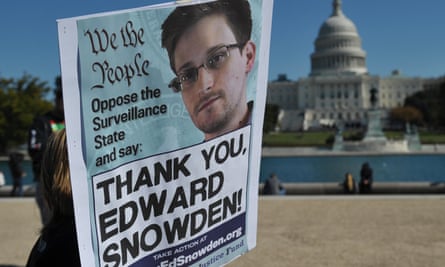

It was the day his life changed forever. When Edward Snowden blew the whistle on mass surveillance by the US government, he traded a comfortable existence in Hawaii, the paradise of the Pacific, for indefinite exile in Russia, now a pariah in much of the world.

But 10 years after Snowden was identified as the source of the biggest National Security Agency (NSA) leak in history, it is less clear whether America underwent a similarly profound transformation in its attitude to safeguarding individual privacy. Was his act of self-sacrifice worth it – did he make a difference?

“I wish things had changed more than they have,” says Jameel Jaffer, executive director of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University in New York. “I would say that the Snowden disclosures made a huge difference to how informed public debate is about the government’s surveillance activities.”

Snowden grew up in North Carolina and suburban Washington, where his father served in the US Coast Guard and his mother worked as a clerk at the NSA. His early obsession with technology – he hacked the Los Alamos nuclear laboratory network as a teenager – led him to a career as a CIA and NSA systems engineer.

Snowden was disturbed to see how NSA analysts used the government’s collection powers to read the emails of current and former romantic partners and stalk them online. One particular NSA program, known as XKeyscore, allowed the government to scour the recent internet history of ordinary Americans.

He concluded that the intelligence community – supposed to keep Americans safe and prevent a repeat of the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks – had “hacked the constitution” and themselves become a threat to civil liberties.

He decided to go public, knowing that his life and career would be upended. He emptied his bank accounts, put cash into a steel ammo box for his girlfriend and erased and encrypted his old computers.

In 2013, Snowden summoned a small group of journalists – Ewen MacAskill of the Guardian, columnist Glenn Greenwald and film-maker Laura Poitras – to a cramped hotel room in Hong Kong to disclose classified secrets about the government’s sweeping collection of Americans’ emails, phone calls and internet activity in the name of national security.

On 6 June 2013, the Guardian published the first story based on Snowden’s disclosures, revealing that a secret court order was allowing the US government to get Verizon to share the phone records of millions of Americans.

The impact was dramatic. James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, who earlier that year had testified to Congress that the NSA did not collect data on millions of Americans, was forced to apologise and admit that his statement had been “clearly erroneous”.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed a constitutional lawsuit in federal court. It eventually led to a ruling that held the NSA telephone collection program was and always had been illegal, a significant breakthrough given that national security surveillance programs had typically been insulated from judicial review.

On 9 June 2013, the Guardian revealed Snowden’s identity at his request. He said: “I have no intention of hiding who I am because I know I have done nothing wrong.”

Later stories in the Guardian and Washington Post disclosed other snooping, and how US and British spy agencies had accessed information from cables carrying the world’s telephone and internet traffic. The reporting triggered a national debate about the extent of government surveillance.

Peter Kuznick, a history professor and director of the Nuclear Studies Institute at American University in Washington, recalls: “The exposé was so in people’s face on television, the newspapers. It was across the board and it was very shocking. It was one of those moments that just catches you off guard and you are going to remember the rest of your life.

“I’m old enough to have been involved in the Vietnam anti-war movement, so we were always certain that our mail was being read and our phone conversations were being tapped. This did not come as a major revelation to most of us; it came much more as confirmation.”

President Barack Obama’s administration claimed that the leaks caused damage to national security, including tipping off al-Qaida and other terrorist groups to specific types of US electronic surveillance. But pressure from activists and members of Congress forced the White House to declassify many of the details surrounding the surveillance programs and how they work in an effort to reassure Americans that the NSA was not spying directly on them.

The Obama administration appointed a high-level panel to review cybersecurity, intelligence and surveillance practices; the panel recommended sweeping changes, some of which were adopted. And for the first time since the 1970s, Congress legislated to restrict, rather than expand, the surveillance authorities of the intelligence community.

Jaffer, the Knight First Amendment Institute director, comments: “It is absolutely clear that Snowden disclosed information that should not have been secret, that the public had a right to see. The significance of the disclosures is difficult to dispute at this point because federal courts invalidated major government surveillance programs because of those disclosures. Congress changed the law because of those disclosures.

“President Obama revised an executive order that relates to how the US government deals with non-Americans’ communications. All this would not have happened but for those disclosures and now the focus should be on what else we need to do to ensure that the government surveillance activities are subject to democratic oversight.”

Jaffer, a former deputy legal director of the ACLU, also believes that the media exposure of Snowden’s documents has made the public much better informed about the NSA and its activities.

“Snowden’s disclosures compelled the government to be more transparent, both in response to the disclosures directly, but also indirectly there was this recognition among many government officials, including in the intelligence community, that the secrecy surrounding the government surveillance activities just could not be defended any more.”

The US media has previously been criticised as too deferential to authority, for example during the Iraq war. But Snowden’s lawyer, Ben Wizner, agrees that one of his most important legacies is a new spirit of fearlessness.

Wizner, also director of the Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project at the ACLU, says: “The courage that the Guardian reporters and editors showed in the face of unbelievable pressure was not only significant at the time but has actually emboldened, at least in the US, the media across the board.

“They’re much less willing to be bullied by the White House or the intelligence community out of publishing newsworthy stories. One of the legacies of the Snowden revelations is a more aggressive and more confident media when it comes to reporting on national security secrets.”

There is a counter-narrative, however. The legal and political reforms that came in the wake of Snowden’s revelations arguably just tinkered around the edges. Wizner acknowledges that many of them were too modest to deal with the scope of the surveillance problem. Others suggest that the national security state has become even more powerful.

Speaking from his home in Brazil, Greenwald, host of the streaming show System Update, comments: “The US government is still spying in ways that are in some instances worse than or more extreme than what we were able to reveal in the Snowden reporting.

“The technology has improved and one of the things that the US security state is expert at doing, and has been since it was created at the end of world war two, is ensuring that Americans always have a new enemy to fear and always have a reason to believe that it’s necessary the government be able to operate in secret and spy and have unlimited powers.”

While Snowden raised public consciousness about mass surveillance as never before, the voters and those they elect did not necessarily follow through.

Jeremy Varon, a history professor at the the New School for Social Research in New York, says: “There were modest tweaks to what the NSA could or couldn’t do, had to disclose or not, protocols for Fisa [Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act] warrants, etc, so conversation was opened up but it didn’t result in a significant clawing back of the powers of the American government.

“There’s a kind of bipartisan national security consensus, and Democrats and Republicans alike, at the end of the day, left the powers of the NSA mostly intact. It’s not much ado about nothing but institutional and policy and legal changes are much harder than simply raising critical questions.

“Most Americans probably never followed the detail and certainly have lost the thread of the specific concerns that Snowden raised; probably some tiny percentage of the people could even tell you any longer the substance of his disclosures.”

Varon continues: “One shocking thing in general is how quickly we seem to have moved on from the entire war on terror era, where it feels very far away and long ago. I wonder in 30 years if Snowden will be any more than a sort of tiny footnote in the American mind, in contrast to somebody like Daniel Ellsberg who, half a century later, is substantially regarded as a significant historical figure.

“I would have thought that about Snowden seven years ago and not so much any more. Americans don’t have a very high historical consciousness and the ferocity of the Trumpian assault on democracy has been so powerful that it wiped away everything that came before it – a hard pivot in the national narrative that no one saw coming.”

As for Snowden himself, some hailed him a hero, the most consequential whistleblower since Ellsberg released the Pentagon Papers. But former vice-president Dick Cheney called him a “traitor” who “committed crimes”. That view is still prevalent in the national security establishment.

Michael Hayden, former director of the NSA and CIA, says: “It was very bad for the United States. We spy. OK. That’s what we do.” The NSA, he added, “lost a lot of collection”, because of Snowden. “It’s not a solution. It’s a problem.”

Asked if Snowden should be allowed to return home and be pardoned, Hayden replies: “God, no. He went to Hong Kong and then went to Russia. What do you think about that? It tells you a lot about him, I think.”

John Bolton, a former national security adviser, adds: “That kind of leak can have a huge negative impact, not just on defence issues but on diplomatic issues as well, because it reveals a lot of specifics and details that a foreign intelligence service could put together.

“It’s the mass of data that Snowden put out, in his case with clear hostility toward the United States – hostility enough that he took Russian citizenship. It’s not the cold war any more but it is going over to an American adversary and that’s pretty serious. He showed his true colours. If he had wanted to fight for his principles, stay in the country and fight for them.”

After his meetings with reporters in Hong Kong, Snowden had intended to travel – via Russia – to Ecuador and seek asylum. But when his plane landed in Moscow, he learned his US passport had been cancelled. He spent 40 days in the airport, trying to negotiate asylum and, after being denied by 27 countries, settled in Russia.

His longtime girlfriend joined him in Moscow and they are now married with two young sons. Snowden gained Russian citizenship to ensure the family could live together but also remains a US citizen. He has been a vocal critic of President Vladimir Putin’s regime.

Turning 40 later this month, Snowden continues to work as a digital privacy activist and often does online public speaking. He has been active in developing tools that reporters can use, especially in authoritarian countries, to detect whether they are under surveillance. He remains outside the reach of a US justice department that brought Espionage Act charges that could land him in prison for up to 30 years.

His lawyer Wizner says: “For people of goodwill who are uncomfortable with Snowden sitting in Moscow, given the global events that are taking place right now, I would say if you think he should be in a prison cell, that is at least a coherent alternative to where he is right now. But if you don’t think that he should spend decades in prison and you don’t want him to be in Moscow, help us find a third option, which we don’t have right now.”

It has been a long decade for Snowden, America and the world. But he has repeatedly said he has no regrets about acting on his conscience and sharing the NSA files in that Hong Kong hotel room. Like Ellsberg, he only wishes that he had blown the whistle sooner.

Wizner says: “History is generally kind to the whistleblowers and history is generally derisive to exaggerated claims of harm to security.

“One thing that is remarkable 10 years after the Snowden revelations is that you can search high and low and, despite the enormous motivation of the US government to paint him in the harshest possible light, you will not find any coherent statement by any US security official that says clearly what harm was done by these disclosures. It doesn’t exist. There is nothing and I’m continually astounded by that.”