Navigating Beatriz Milhazes’ febrile reinvention of geometric abstraction can feel like trying to make headway through a carnival crowd. Hoops, mandalas, flowers and other circular motifs spin like dancers across her canvases, their bright colours slamming into each other. With its erupting forms, which have evolved from tumbly, lacy arabesques to hard-edged grids, sprouting leaves and flowing waves, the Rio de Janeiro-based artist’s work has the excess of a street party, a baroque church, a jungle.

“I’ve tried to bring new possibilities to the course of abstraction,” she says while getting ready for her first UK institutional show in more than two decades: a survey, at Margate’s Turner Contemporary, of 20 key paintings spanning her 30-plus year career as one of the world’s leading abstract painters. “My challenge is how to work with geometry and life. I’m in favour of life, we need it!”

Milhazes recalls how, when she studied art in Rio in the 1980s, painting had been a lesser force in Brazil’s cultural scene. Instead it was dominated by the Tropicália installations of Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticia that melted boundaries between art and life. So Milhazes looked to Europe. Her first and enduring touchstones included Piet Mondrian and his interest in nature and structure as well as Henri Matisse, a forebear in collaged shapes, vivid colours and the pursuit of beauty, with whom she felt “the deepest connection”.

To bring new heat to these ideas she turned to Rio, taking inspiration from its architecture and vernacular culture. Her graduate works collaging spangled carnival fabrics were inspired by the spectacular creations of the great carnival designer Fernando Pinto, while historical dress and women’s domestic labour making lace and crochet was another early reference. In 1989 she began developing her signature transfer technique, using cut-out plastic shapes loaded with paint to imprint forms on the canvas. The resulting surfaces have intense colours but are not poster-smooth. Rather they’re visibly layered, textured and cracked.

At Turner Contemporary, Milhazes’ earliest paintings will come as a surprise to those familiar with the artist’s later bold abstractions. Recalling lacework, wallpaper and floral fabric prints, their patterns are looser and more obviously hand-worked. Flowers, though, are a constant motif and not just because of what Milhazes sees in Rio’s famed botanical gardens or national park. “They ornament the sad moments, the beautiful moments, and are part of people’s life,” she says.

As her vision progresses, the compositions become staggeringly complex. In Maracorola, an enormous 2015 painting of almost three metres, she composes a landscape with pulsing hoops, waves, vegetal squiggles and a blazing sun across a chequerboard ground. It’s a controlled riot of form and colour, with two key motifs: the circle and wave. “The circle is an organic shape and has no end,” she says. “It’s spiritual and meditative. My interest is more about movement, though. You never really find the centre in my work. I call it a mathematical dream.”

Inspired by Rio’s coast and parks, Milhazes has grown more interested in nature lately, and it is a focus of her Margate exhibition. “We’ve done so much damage; it’s not just about stopping that but also examining our hope for nature to renew,” she says. “I’m an optimist and I want to show how much we need the breath of the leaves, the water, sky and sun. My work is about life. Wherever it’s shown, people connect to it.”

Beatriz Milhazes: Maresias is at Turner Contemporary, Margate, 27 May to 10 September.

Circles of influence: four works from Maresias

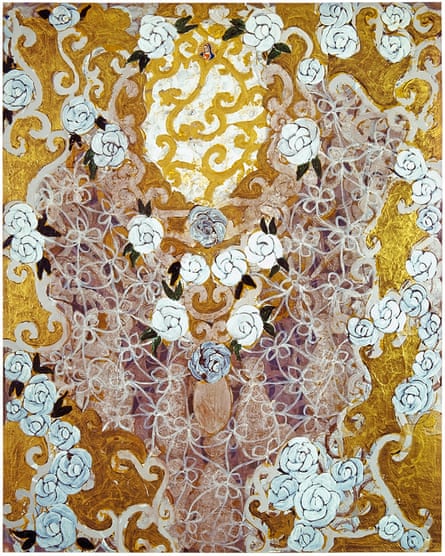

Douradinha em cinza e marrom, 2016 (main image)

This eye-popping recent work, whose geometric forms pulse outwards from its citrus centre, shows Milhazes’s pioneering use of figurative elements – here flowers and leaves – in abstract painting.

Maracorola, 2015

Milhazes sees this vast painting as combining key aspects of her development as an artist, including how she thinks of composition in terms of landscape’s possibilities. It explores the sea’s rhythms, seen clearly in the rippling waveforms.

Maresias, 2002

This work gives Milhazes’ exhibition its title, and means “sea air”. Like one of her forebears, the avant-garde French artist Sonia Delaunay, Milhazes has explored buzzing circular forms. This painting suggests multiple references, from mandalas to targets and floral decoration.

A Casa da Maria, 1992

In one of the earliest works in the show, Milhazes draws on the history of dressmaking and women’s domestic labour in Brazil, referencing “the kind of crochet my grandmother used to do”. Its gold palette recalls church ornamentation.