When the Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury in 1948, passengers disembarking included Trinidadian calypsonians Lord Beginner, Lord Woodbine, Monica Baptiste and Lord Kitchener, the latter serenading the Pathé News film crew with an a cappella version of his song London Is the Place For Me. Until the Commonwealth Immigrant Acts (1962, 1968, 1971) produced a hostile environment for Caribbean nationals wanting to emigrate, many West Indian musicians would follow them, introducing everything from ska to soca. A handful of them would achieve international success; others would be broken by their experiences. Most were overlooked and would endure many privations, but they all enriched British music in myriad ways.

“I suppose we made some kind of impact,” says the self-effacing Michael “Bami” Rose as he reflects on their legacy ahead of this week’s Windrush 75 commemorations. Bami is preparing for tonight’s residency at Brixton’s Effra Tavern with Jamaican Jazz, an ensemble formed in the early 1990s that paired veterans – Rose, the late trombonist Rico Rodriquez, percussionist Tony Uter, trumpeter Eddie “Tan-Tan” Thornton – with younger Black British players. Rodriquez died in 2015 and Thornton is ailing, but Rose and Uter, 80 and 94, respectively, continue to lead a dynamic outfit. “Musicians play until their teeth drop out!”, Rose says.

Having left Jamaica for Britain in 1962 and then co-founded pioneering Black British band Cymande, Rose has since played on countless recording sessions (including Aswad’s Warrior Charge), and is a longstanding member of Jools Holland’s Rhythm & Blues Orchestra. “Back then, we all listened to the West Indian jazz musicians who were playing here,” he says, including the aforementioned Rodriguez (who would later play the trombone riff on A Message to You, Rudy – both Dandy Livingstone’s original and the Specials’ hit cover). “He was a great help to me when I first got here, he introduced me to many people. He had that great sound: so full!”

Rodriguez is also acknowledged by Uter who learned to drum in Kingston’s Salvation Army band before playing with Rastafarian drummer Count Ossie, cutting cane in Florida (“brutal!”) and working his way to Britain playing congas in a ship’s calypso band in 1959. Since then he has played with many musical greats. “Ronnie Scott, Dizzy Gillespie, Keith Tippetts, Tubby Hayes – I play with all the jazz men,” says Uter, smiling at the memories, “and through Rico I play with Prince Buster and plenty other, including Bob Marley. We tour with Bob in 1977 and he a really down to earth man. We tight!” Uter has also worked closely with Linton Kwesi Johnson and today regularly plays alongside Errol Linton and Diz Watson. Is he, I ask, the oldest working musician in the UK? “Me not sure, but one thing for sure,” says Uter with another wide smile, “I love to make music. My son ask, ‘when you retire?’ and I reply ‘never’. Music’s been good to me and it good for me.”

The Windrush musicians forged contemporary jazz alongside their British and African contemporaries – 21-year-old Fela Kuti honed his chops playing trumpet in a multiracial north London jazz band – while working on calypso, ska, pop, rock and reggae sessions: the irrepressible Tan-Tan joined Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, played on the Beatles’ Got to Get You Into My Life and was adored by the Small Faces (who wrote Eddie’s Dreaming for him).

Initially, calypso sold strongly with Kitch, Beginner and Baptiste releasing remarkable records on London’s Melodisc Records. “Calypso was the popular sound in Jamaica in the 1950s,” recalls Uter. “We play it in hotels and on the street and this is how I begin to make a living making music. It get things started for many of us.” Melodisc’s Austrian founder Emile Shalit then launched Blue Beat Records in 1960, focusing on Jamaican music, and its success encouraged Ska Beat, Island, Pama and Trojan Records to follow suit, making London a hub for ska, rocksteady and reggae.

“I arrived in London from Jamaica aged 11 in 1960,” says Glenroy Oakley, vocalist for Greyhound, a British reggae band who scored three Top 20 hits in 1971-72. “It was a nice time – we played Mick Jagger’s wedding, toured with Bob and Marcia and Toots; Tony Blackburn made Black and White his record of the week. I don’t think we got the recognition we deserved – reggae wasn’t taken very seriously back then. We were on Trojan and while they were good to us that label was pretty wayward.” He chuckles and adds, “but I enjoyed myself and so much wonderful music was made”.

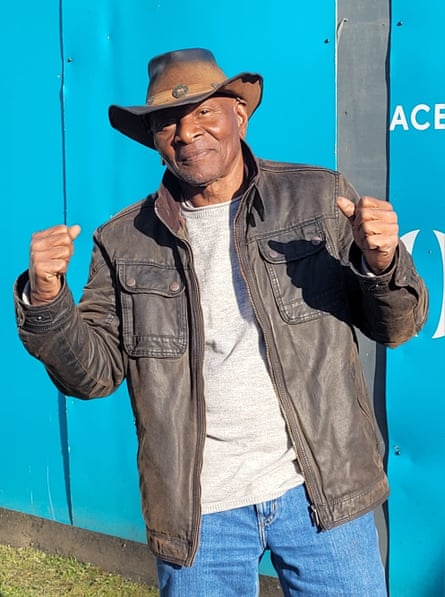

Windrush-era R&B was even more overlooked, but one who attempted it – along with Carl “Kung Fu Fighting” Douglas and Jackie “Keep On Running” Edwards – was Jimmy James, now 83, who arrived in London as vocalist with the Vagabonds in 1964. “We brought a hell of a lot: music, fashion, food,” he says. “Even now the kids try and speak like Jamaicans. At the same time, we had to put up with discrimination: ‘no Irish, no Blacks, no dogs’. How can people be so ignorant?”

Originally intent on performing for West Indian audiences before returning to Jamaica, the Vagabonds were discovered by Pete Meaden, the Who’s mod mentor, who convinced them to stay and produced their 1966 album The New Religion. The Vagabonds became mod icons, entering the Top 40 in 1968 with Red, Red Wine – the first version to chart – while James later scored several disco hits.

“We didn’t understand rock music at the time,” says James, “so, when we started supporting the Who, we used to laugh and say ‘they must be on drugs!’ They had a lot of anger and that came out in their music. I’ll say this about the Who – they saved our lives. Our van with all our equipment in it got stolen and Roger and Pete and Keith went into all the music shops and got us new keyboards and guitars and drums. For that we are eternally grateful.”

The Who probably were on drugs – amphetamines – while West Indian musicians preferred marijuana. Uter mentions how he began smoking ganja aged 14 and, 80 years on, continues to puff, believing it helps him keep healthy. “Cocaine hurt musicians – look at Tubby Hayes! – but not ganja,” he says, adding “me smoke with everyone” as he lists musicians before detailing how Sammy Davis Jr would, when performing at London nightspot The Talk of the Town, rush up to Ronnie’s during his break, find Uter and the two musicians would go for a smoke up on the club’s roof. “Nice man, Sammy,” he says.

Using the Empire Windrush as a catch-all for the UK West Indian community’s history has rightly been criticised as reductive; noted Caribbean musicians were based here prior to the second world war, such as trumpeters Leslie Thompson and Jiver Hutchinson and bassist Coleridge Goode. Trinidadians Edmundo Ros and Winifred Atwell settled in London in 1937 and 1945 respectively, both achieving huge success: Ros’s Latin band – who Uter joined when he first arrived in London – had a fan in Princess Elizabeth while Atwell became the first Black woman to top the UK charts.

But it was the calypsonians who first forged a distinctly Caribbean musical identity in Britain, compounded by steel pan bands who began here in 1951 when Sterling Betancourt decamped from the Trinidad All-Steel Percussion Orchestra’s European tour to stay in Britain. Jamaica’s musical culture grew stronger still when Duke Vin and Count Suckle both set up sound systems at West Indian parties in the mid-1950s – they organised the UK’s first soundclash in 1958. Today, steel pan and sound systems are mainstays of Notting Hill carnival and part of popular music’s DNA.

“When we first here there not many clubs that welcome Black people,” says 81-year-old Wally Bryan, “so we take the sound system inside a house and make a party”. Bryan, who runs Supertone Records on Brixton’s Acre Lane and The Mighty Supertone sound system, arrived in 1964. He points across Acre Lane to a house and says, “I’d put my sound in a three-storey house like that and 500 people would come. We like it close!”

Both Bryan and James recall the shock of UK closing time. “The concierge told the band to stop playing at 11pm on our first concert,” says James, “and I asked, ‘what did we do wrong?’” He laughs. “In Jamaica we’d just be getting warmed up at 11pm.” “Sound system play music all night,” says Bryan. “Party finish 5am, maybe 9am.”

Bryan has run Supertone Records since 1983 and seen its clientele change from locals queueing for new tunes “from the yard” to online sales now surpassing those across the counter. “The record shop was important for Jamaicans,” he says, “it a place for us to gather and enjoy ourselves. Still is.”

The ranks of Windrush era musicians who reshaped British culture are thinning – Errol Dixon, the pianist-singer whose 1961 single Midnight Train helped establish the Blue Beat label, died suddenly last January having spent the past four decades based in Switzerland (where he still performed 150 nights a year), while sound system don Jah Shaka died in April. After 60-plus years of performing, Jimmy James retired last year due to mobility issues; Dizzy Reece and Ernest Ranglin, once transplants to the UK, remain semi-active nonagenarian musicians in New York and Jamaica respectively. The formidable Eddy Grant – who left British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1960 to join his parents in Kentish Town aged 12 – sued Donald Trump for using Electric Avenue on the campaign trail and pulled all his music from streaming services.

The music of these pioneers has gained wider recognition thanks to compilations and reissues in recent years by labels Honest Jon’s, Cherry Red, BGO and Cadillac Records, and was prominently featured in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe TV series, but the longstanding ignorance, neglect and even outright hostility still rankles. “We were fortunate to make a good living but have never really been acknowledged,” says James. “West Indians were asked to come here to help rebuild Britain. We did this – and much more. Some people acknowledge it, while others still mutter about us being here.” He says that the Mobo awards have never honoured his generation. But he takes solace in their legacy: “What we did, we did it well.”