Not to deny the appeal of books and podcasts in which successful people talk inspirationally about failure, but a new, quite different school of anecdotal evidence proposes an alternative approach. What if the most effective way to deal with failure is to deny it ever happened? Or – supposing something outwardly catastrophic is perceived definitely to have occurred – to explain how this narrative merely confirms the harsh challenges confronting the targeted idealist/saviour/innocent workhorse?

“When the herd moves, it moves.” (Boris Johnson)

“Last autumn I had a major setback.” (Liz Truss)

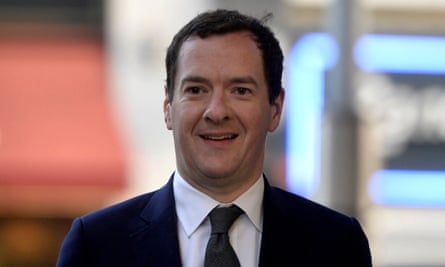

“I had a really golden time personally.” (George Osborne)

If spectacularly failed Conservative politicians can’t take all the credit for this self-soothing approach to recorded disaster – Jeremy Corbyn and others serve unapologetically elsewhere – they offer masterclasses in failure management unlikely to be surpassed until another party favourite challenges the convention that a legacy of national pain is incompatible with career advancement.

Truss being the Elizabeth Day of this revolution in failure management. Join us to not discuss what she didn’t learn from a failure that never happened. Her progress with self-vindication – as last week in Taiwan – might look paltry besides Osborne’s majestic exercise in renewal, or Johnson’s travelling circus, but the former has time on his side, the latter his fictions, showmanship and bewitched sponsors.

Considering how many households are likely to have suffered more financial pain from Truss than they would from a mobile phone robber – and how some may even recall the missing Chevening bathrobes of yestermonth – Truss’s return from the wilderness, before she’d even been reported missing, would seem insanely misjudged if it weren’t more reminiscent of a triumphant Richard III. That bit where he seduces the widow of a man he recently murdered. Over another body. “Was ever woman in this humour woo’d? Was ever woman in this humour won?” That’s how mad – or impressive – it is to see news organisations that lately charted the £30bn cost of Truss’s idiocy now recording her pronouncements with a polite interest almost indistinguishable from complicity.

Actually it’s madder: Shakespeare’s Richard III pretends to be penitent. Last week Truss simply stumbled through enough pronouncements on China to persuade the gullible to promulgate the selfies she has always considered, her biographers confirmed, critical to her interests.

“Truss urges Sunak to class China as a ‘threat’ to UK security”, was the BBC’s dutiful take, as if this was (a) news outside her head, and (b) really the point of the Taiwan-themed step in Truss’s rehabilitation. Since the report sought balance from her party critics, but not from civilian victims of the “moron risk premium”, a popular term she inspired as long ago as last October, this adventure could hardly have gone better for one of the most charmless vandals in recent political history. Though she is obviously fortunate in that respect to benefit from the pioneering example of Osborne.

It’s thanks to Osborne, past master of failure burial, that we know that public loathing and professional suspicion can dissipate to completely safe levels in as little as nine years. That was the gap between Osborne being booed at the London Paralympics when people still resented his assault on public services spending (including on museums), and his being made chairman of the British Museum.

His record as chancellor, condemned both before and after the career-change that followed his and David Cameron’s risk-taking on Brexit, had not, of course, come between him and a succession of other unlikely but fault-erasing jobs, including editing Evgeny Lebedev’s Evening Standard.

Today, burnished by his British Museum connection, fresh promotion for the creator of the bedroom tax will be reported (he’s to ornament the Lingotto investment company), without anyone asking why you’d hire someone who, as well as wanting Theresa May chopped up “in my freezer”, was for so long associated with being amazingly wrong. Not only on austerity, although that would be enough, but on HS2, on the garden bridge and most memorably, if remembering is your thing, on China. He led a fawning delegation there in 2015: “Let’s create a golden decade for the UK-China relationship”. If he’d got his way, the love affair would still have two years to run.

In return, China’s state press praised Osborne for setting aside human rights objections, which already included the persecution of the Uyghurs. “Keeping a modest manner is the correct attitude for a foreign minister visiting China to seek business opportunities.”

Last week Alastair Campbell, after inviting the modest statesman on to his podcast The Rest Is Politics, said Osborne had “some good advice for Labour”. Hopefully someone in Labour recalls that in 2019 Osborne, backing Johnson, told Standard readers his candidate could “put his party, and country back on track”.

With his recent Elginwashing helping complete the removal of what once appeared unshiftable reputational stains, Osborne’s reinvention, eased by only the mildest expressions of regret, is a reassuring template for any politician with zero deniability for their part in the UK’s post-2010 decline. What might not be forgiven by the public will be soon forgotten, or, with enough bravado and new job titles, overwritten.

Likewise, whatever becomes of Johnson, the rebukes that triggered his exit already read like historic documents, barely related to the prosperous figure who, having derailed both his party and country, has just acquired the ultimate stamp of Tory respectability, a moated manor. Perhaps Carrie has yet to read Alan Clark’s diaries.

Whether the Tory way with failure will benefit failures outside the party probably depends on the allegiances of the failed. A moron risk premium that the Mail or Telegraph forgave from Truss, they would not from Keir Starmer. But the willingness of more neutral news sources to quote the unrepentant Truss with little or no allusion to her dreadful previous, hints that where shame has already gone, failure could still follow.