The plane’s engine groans, and its small frame rises. Through a thin membrane of cloud, the spine of the southern alps rises like a dark sawblade.

“I’m wondering if my favourite glacier is going to be there,” says principal climate scientist Dr Andrew Lorrey. “We’ve had a really, really hot one this summer. It’s hard to say. We’ll just have to see how they’ve gone.”

In the pre-sunrise darkness of Sunday morning, the small group of six scientists had gathered on the asphalt of a small Queenstown airfield, packing cameras into backpacks as a wash of colour leaked over the mountains. For most of the next eight hours, they would sit twisted in their seats, spines cramping, lenses trained to the windows to capture the peaks of the southern alps as they emerged from thickets of cloud. This is New Zealand’s annual snowline survey, a single annual charter flight run by climate research institute Niwa that attempts to capture the state of the country’s glaciers before winter sets in. Today, on the back of two record-breakingly hot years, the scientists are bracing for the worst.

As the tiny plane curls around the peaks, the pilot flicks between different maps on a tablet, comparing notes with the science team through a headset to try to track the precise location of glaciers through the cloud cover.

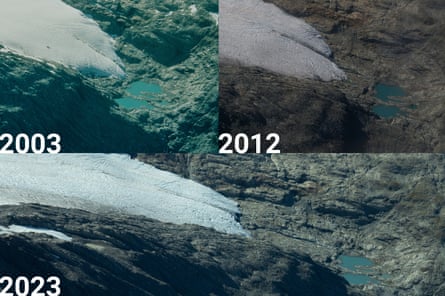

Out the far window, the blue-grey expanse of Brewster glacier looms to the right. The larger glaciers, like Fox and Franz Josef, are shrunken but still confront you as huge rivers of ice, wrinkled and cracked by the pressure of their downhill flow, a thick ribbon of crumpled pale blue crepe. Across others, however, veins of dark rock are emerging, eating deeper and deeper into the glaciers’ pale centres. Brewster’s layers of ice look like a slice of quartz, rippled with thin ribs of black scree and apricot sediment. The thick snow and ice that might once have covered it has retreated, replaced with the dark sheen of newly exposed rock.

“It’s really dramatic,” says prof Andrew Mackintosh, the lead scientist on the exhibition, turning back over his headrest to yell over the roar of the engine. “I wouldn’t have imagined to have seen changes like that in my lifetime – it’s quite profound.”

Mackintosh, a glaciologist now based at Monash University in Australia, helped launch the monitoring programme at Brewster glacier in New Zealand in 2004. At the time, it was thick and healthy. “It’s 20 years later, and I just wonder how … ” he trails off. “It will take a while to fully waste away, but it doesn’t have the characteristics of a happy, living glacier any more. It looks like something that is just decaying, and won’t be with us much longer.”

A confronting sight

There is a grief in watching the ice melt. Some of these scientists have been monitoring these glaciers for decades, returning every year to take their pictures. They know each by name, and have their personal favourites. Some of the glaciers they used to record have vanished over the last decade. Mackintosh and Lorrey occasionally lean over their grey vinyl seats to exchange observations, gazing out the shuddering windows. “She looks like shit,” one of them says.

“It’s interesting as a scientist, and a bit challenging as a human being to see that change,” Mackintosh says. “There’s a kind of conflict: of fascination in how the system can change so rapidly, combined with the emotional response of seeing the loss of ice that’s such an important part of the landscape, and so beautiful and so culturally important.”

“The scale of retreat is confronting, even to a glaciologist.”

Over winter, the snow should coat the glaciers and slopes with a thick, smooth slab of marzipan. That snow feeds and protects the glacier, adding to the ice’s volume before the warmer months can strip it away. Typically, a glacier will accumulate snow at its top and slowly melt from its lower reaches, forming alpine lakes and tarns, and feeding the braided rivers below. But the extent of warming temperatures are changing that dynamic even at high altitudes, sending the ice on glaciers like Brewster contracting even at the higher reaches. “This is a glacier that’s melting all over – at the top and the bottom and the sides, just bringing the whole thing in,” Mackintosh says.

As the seasonal climate has warmed through spring and through summer, that snowline peels up. As the plane circles the rear of Mount Bryant, Lorrey points to where the snow has pulled back from the ice. “You see that ice here? All the bluish ice is completely bare, it’s been stripped off. … So that whole glacier, pretty much 80%, 90% of it is melting. Anytime you see blue ice, it’s naked,” he says.

He shakes his head slightly. “That’s emaciated.”

As the plane comes in to land at Lake Tekapo’s airfield, Lorrey points out the folds and drainage channels in the plains. “18,000 years ago, this whole valley was filled with ice,” he says. But if the movement of ice was once measured across hundreds or thousands of years, it is now moving far faster, retreating from rising temperatures over the course of years or decades. 2022 was New Zealand’s hottest year on record – the second year in a row the record’s been broken.

The flight attempts to document the snowlines on more than 50 glaciers, some of which have been monitored like this for the last 46 years. But over time, some of the index glaciers have been substituted out as they disappeared, swapped for cousins in the higher reaches. Now, even some of those replacement options are looking thin, and Niwa predicts that many of New Zealand’s important glaciers will be gone within the decade.

There is still hope for the glaciers that remain, Lorrey says. A few fractions of degrees of warming are the difference between New Zealand’s glaciers clinging on, or disappearing completely.

“Rapid change is needed, rapid action is needed to change the pathway that we’re on,” Lorrey says. The damage can be done quickly, but the repair is much longer. “These abrupt and absolutely rapid [losses] can happen in a few shockingly warm years,” he says, “But it’s a glacially slow process to replenish that ice and rebuild it to its full glory.”

“We know what’s driving the loss of glaciers,” Lorrey says. “We know that there’s an intimate connection between temperature change, and the changes that we’re seeing in our glaciers. … We know that that pathway is very much dictated by CO2 emissions.”

“It is a bit emotional to see an amazing, pristine part of our natural environment, slipping through our fingers. I would like to share it with my family and my friends and especially my daughters, and I don’t know if I’m going to have that opportunity … It’s going so fast.

“We need to confront this in a much more direct way, in a faster way.”

In the end, Lorrey’s favourite, Llawrenny Peaks, was impossible to document this year – wrapped by thick cloud, impossible to see from the plane’s windows.

“In a way I’m kind of glad,” he says. “Because I suspect I might’ve cried if it was not there.