It was the sense of order that first struck me arriving at Wimbledon last Monday. The queue is the most well run and efficient. The security office where I collected my pass was the most immaculate I’ve ever seen; the attendant’s uniforms were spotless, the clocks were by Rolex.

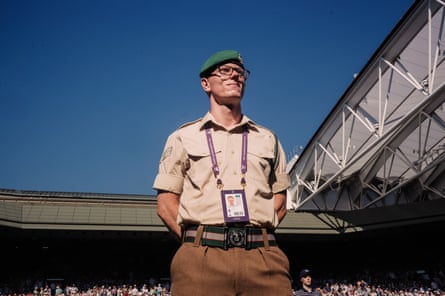

That order continues once you’re on site. There are smartly turned-out young members of all the armed services (including the “redcaps” of the military police) helping with both security and directions. There are perfect crocodiles of ballboys and girls marching at a regulated distance apart. With their socks all pulled up to an agreed length.

There are water refill stations wherever you might need them. The line judges, and greensmen and greenswomen (I had to look them up, but they’re the young people, older than ballboys and ballgirls, but uniformly at least two decades younger than me, who wear green and who hold the umbrellas above the players as they rest between games) are all head to toe in Ralph Lauren.

I’ve always liked the commitment Wimbledon and the All England Club has to its visual identity. The green and the white of the courts, the player’s whites stripped of all but the smallest emblems from their sponsors.

When Ralph Lauren first sponsored the uniforms some thought they aped a “Britishness” that seemed too self-conscious. An American’s idea of what British people are; a preppy version of Frasier’s Daphne. But they were wrong. That’s what is genius about the uniforms: the white collars and immaculate peaked caps of the line judges speak to a nostalgia for something that never was. The slight unreality seems to mitigate the possibility for jingoism. Wimbledon feels as British as The Wicker Man does, but not sinister, and not political. The flag is green purple and blue rather than red white and blue.

Everyone working at the tournament has a uniform of some sort even the photographers. All of us fortunate to secure a pass are issued the sleeveless, mesh pocketed jackets beloved of anglers and supporting artists dressing as press photographers in ITV crime dramas. I would usually have been embarrassed to wear that get up, but there’s no point being embarrassed when everyone else is also wearing them, and it turns out lots of big pockets are actually quite useful.

There are not a huge number of photography passes issued, and I was extremely grateful to have received mine. Obviously most photographers there are sports photographers, and they’re the best in the world at this. I am definitely not a sports photographer. I walked past the open laptops, with shots from the courts, in the photographer’s centre in awe, feeling like a fraud carrying just my small rangefinder with a prime 35mm lens and an old 1980’s flashgun.

I wanted to commit to one style and one technique. I like the way a fill flash, particularly when used on a bright sunny day, can give a slightly hyperreal effect.

-

Zachy, 6, is autistic. His mother felt this picture of him enjoying the event may encourage other parents of autistic children.

And I like the personal challenge of using just one specific lens for a series of images. I find it means you really have adjust the way you think and see through the lens rather than the other way round. Here, this way of working presented a challenge, in that you most definitely are NOT allowed to use a flash courtside for very obvious reasons.

Rather than filing a series of Wimbledon images with no actual shots from the tennis courts, I asked a photographer friend with years of experience of working there to tell me which side of the court to sit and at what time when the light would be low and directly behind me so that it would visually match with the images taken with a fill-flash. It’s a “cheat”, but I’m Ok with that in the circumstances.

The final shot of Andy Murray does slightly bend the rules I’d set myself with light, but it is shot on a 35mm. He’s my sporting idol, and sitting courtside and seeing him play on Centre Court, and hearing both his roars and the crowd was both a thrill and such a privilege.