Live Aid, 1985. In front of 72,000 people and a global audience of more than a billion, George Michael is on the brink of superstardom. He is sharing a stage with Elton John, but really everyone’s eyes are on Michael. There is a lovely moment – one of many – in the great new Wham! documentary, when the camera is on Andrew Ridgeley, relegated to singing backing vocals and positioned somewhere behind Elton’s piano. Ridgeley’s expression is of pure pride and love. There doesn’t seem to be any hint of jealousy in his joyful, beaming face, or sadness that his childhood friend is moving away from him – Michael would become a solo artist the following year.

Nearly 40 years later, Ridgeley is sitting in a room at the Sony offices in London. The Netflix documentary has been a hit, and Ridgeley has been immersed in Wham!, the band he created with Michael as teenagers, for the last few years. There’s also a 40th anniversary rerelease of Wham! singles coming, and he would love to do something with the 51 wonderful, meticulous scrapbooks his mother kept, which feature heavily in the documentary. He is wiry and boyish, articulate but not particularly given to introspection. He will talk and talk about the process of putting together Wham!’s two albums, but on emotional matters – such as Michael’s death in 2016 – he becomes more detached. “Like all losses, one learns to manage them and one comes to terms … ” he says, trailing off.

He is pleased with the documentary, which is true to the spirit of Wham!, “essentially a manifestation of our friendship and our youthfulness”. They blazed brightly – a blur of neon and hairspray and energy – for four short years, during which they produced incredible songs, among them Club Tropicana, Careless Whisper, Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go and Last Christmas. “They each have character,” says Ridgeley. “We grew up listening to a really varied range of music. We never confined our listening to a particular genre. We were fans of everything.”

The boys bonded over music when a 12-year-old Ridgeley was the only child at their Hertfordshire comprehensive school who put his hand up when the teacher asked someone to look after the new boy, Georgios Panayiotou. “We got on right away,” says Ridgeley of the friend he calls Yog. Both had immigrant fathers who had come to the UK escaping conflict – Michael’s father was Greek Cypriot, Ridgeley’s father had been expelled from Egypt during the Suez crisis. Wanting to avoid discrimination, his father renamed himself Ridgeley after a street sign he saw. Later, Ridgeley says that some of Michael’s lack of self-confidence perhaps was “a consequence of being Georgios Panayiotou in 70s England. I was ‘Andrew Ridgeley’, I was as English as you could be, even though my father was Italian-Egyptian-Yemeni. I genuinely think that had some influence on his self-image.”

They shared a love of music, “and an extremely juvenile sense of humour, [which] was the central pillar of our relationship”. They would pretend to do radio shows, “where we’d take off DJs, and we’d recreate scenes from movies. We saw things very much the same way.” Michael was the shy, self-conscious boy – worried about his weight, and with frizzy hair and glasses. It was Ridgeley who was stylish, had a cast-iron self-assurance and felt desperate to be in a band. “I did have to sort of railroad him,” he says. Michael – when he talks about his friend, he often slips into the present tense – “says he always wanted to be a songwriter and an artist, but he didn’t seem to have that when we were growing up – that focus and drive to put aside everything else”.

Ridgeley wasn’t interested in school – “once I could read and write, there was nothing else that was any use to me” – but Michael felt academic pressure from his parents. Ridgeley steamed ahead. Their first band, formed with two other friends, was a ska-influenced group called the Executive, which had some short-lived record label interest before they split. As a duo, Ridgeley and Michael made a demo of three songs – Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do), Club Tropicana and Careless Whisper – at Ridgeley’s house and touted it round record companies. Most passed, until they managed to land a deal in March 1982 – a momentous occasion marked in one of Ridgeley’s mum’s first scrapbooks.

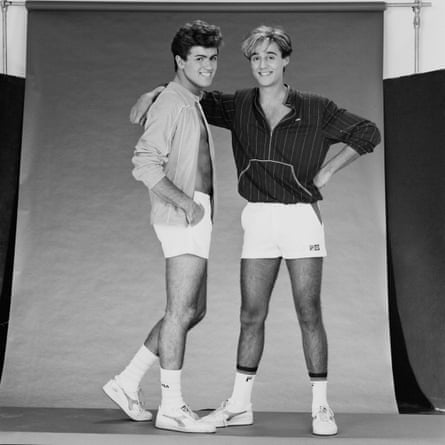

One of the most charming things about them was how amateurish it all was. Shirlie Holliman, a local friend, joined Wham! as a dancer and backing singer. Her friend Dee C Lee came too, and they made up dance routines at home or at clubs. “We wore each other’s clothes because we only had about three outfits between us,” says Ridgeley. “You can see it in the press photos – Yog’s wearing my shirt in one shot, I’m wearing his string vest in another.” He laughs. “But it was authentic.”

The one thing they did take seriously was the music. Later, when Michael recorded Careless Whisper for their second album at the Muscle Shoals studio in Alabama, he didn’t like it, and rerecorded it in London. “So we knew what we were doing [in terms of] writing and making records.”

It was getting on Top of the Pops in late 1982 – a huge deal back then – that saved Wham! from being dropped by their label after their first two singles initially failed to take off. Suddenly, they were huge. What was that like? “Well, life didn’t change for us very much,” says Ridgeley. “Materially, it didn’t change because we didn’t have any money.” Their record contract, signed by two teenagers in a cafe, was not exactly generous; for the second album, their new label got them out of it. “So we weren’t buying big houses and fast cars and living the high life, because we didn’t have any swag.” But the attention, he says, “took us both aback”. He remembers performing a live show in early 1983, where “the atmosphere was really quite visceral. It was at that point I thought, this has another dimension.”

Their early releases had been considered social commentary – Wham Rap! has lyrics about youth unemployment – but they weren’t exactly working-class heroes, as Michael put it in one interview. When Club Tropicana was released, with its video shot in Ibiza, it was far closer to what Ridgeley and Michael wanted to be: sexy, glam, fun. The music press criticised them, but Ridgeley says he didn’t care. “The only people that mattered were the people who were buying records. It was a source of bemusement that the music press had turned on us, but we also understood that the music press took itself very seriously.” They didn’t, he says, “make records for critical acclaim. Recognition is a different kettle of fish, and that did get under George’s skin, far more than it got under mine, because by then he was shouldering the songwriting duties alone. It wasn’t just the songwriting – his ability as a singer was overlooked, and that recognition came a bit late in the day.”

The decision that Michael would take over songwriting while they recorded their first album was, admits Ridgeley, “a little difficult … even though I knew exactly why we were making it and I didn’t try to assert … assert?” He pauses. “Impose a desire to demand to share even part of the songwriting duties, largely because he was so much better at it. It was important for us to make Wham! the biggest pop act of its kind, and that could only be served by Yog assuming the songwriting duties.”

His ego must have been bruised, at least? “I like to think I have a minimal ego. But it was difficult. It did feel uncomfortable to put aside that aspect of my creativity, but I understood the context in which it was being done.” He sounds so rational. No existential angst? “I don’t do existential angst,” he says with a laugh. “My feelings weren’t hurt, but it was difficult, it was uncomfortable, because it reduced my input into Wham!. We started off writing songs together – that had always underpinned music-making.”

He could have carried on writing (he co-wrote some of the best pop songs ever written, after all). Why didn’t he? “Because I’m lazy,” he says, with a laugh. “I think if I’d been advising the 23-year-old Andrew Ridgeley, I would have probably said, you should concentrate on songwriting and develop that, and work a darn sight harder. I was indolent and feckless.”

Ridgeley was mocked in the press for being little more than Michael’s hanger-on, but it didn’t bother him, he says. “It had been present and intimated for so long that it was neither here nor there. Initially, did it rankle? Yeah, I suppose it did. But my position in our relationship, and in Wham!, was incontrovertible as we saw it, so it wasn’t something that affected our relationship.” The Spitting Image puppet of Ridgeley as a pair of dancing buttocks, he says with a laugh, “was quite funny”. With more time, and freed from the pressures of songwriting, as Ridgeley writes in his 2019 memoir, “with no reason not to, I went out more and more and my reputation as a party animal and hell-raiser gathered momentum”.

How did he feel when Michael became a global superstar? “Extremely proud,” says Ridgeley. Standing on that stage at Live Aid, didn’t he wish he was up there with Elton John? “Oh God, I envied his voice and his songwriting talent, but it was an affectionate envy, very different from being jealous or covetous. I respected his talent immensely, but it was also a sense of great pride. He was my best friend and I knew his potential, and it was marvellous to see that become realised.”

Michael came out to Ridgeley during the filming of the Club Tropicana video. He wanted to keep it secret – mainly, he says, because at 19, Michael was “very conscious of what his dad’s reaction might be”. There was also some concern about their career. Ridgeley thought “he had nothing to lose by making it public should he so wish, but he didn’t. You look at Freddie [Mercury] – it didn’t make any difference to Queen’s success, it didn’t make any difference to Culture Club’s success. It’s arguable – would America have taken to George Michael in the way it did had he been out? I think it was perhaps rather more a fraught matter in the US than it would have been here, certainly at that time, and may still be the case today, and would probably have been a factor in his decision not to.”

Would being free to come out have made Michael happier? “I think he feels he would. He could have taken that decision to reveal his sexuality at any point, and he chose not to until it was thrust upon him, I think largely because he felt it was no one’s business but his own. He was intensely private, and I understand that fully, because I felt the same way, perhaps not quite as deeply as he did. He felt it compromised his ability to relax and be comfortable and content in his own life.”

Did Ridgeley have any sense of Michael’s later problems, especially with drugs? It’s a sensitive subject, he says, “with the George Michael estate”, so it’s not something he feels comfortable talking about. But did he worry about him? Michael was arrested in Los Angeles in 1998 for a lewd act in a public lavatory – a very public outing – then several times subsequently for possession of drugs; in 2010, he spent eight weeks in prison for driving under the influence of cannabis. “Some of the things he did were of concern, yes,” he says wryly. “They couldn’t not be, could they? His latter years were not his best, but his best were incredible.”

Their lives diverged after Wham!, but they still saw each other fairly regularly, the last time a few months before Michael died. He had gone to Michael’s Highgate home. “I think I was cooking for him. He had a few friends round.” They played Scrabble, and Ridgeley won. To lose a childhood friend, someone who had shared such a formative experience, “the like of which you don’t make again, was devastating”, says Ridgeley. “But I look back on his life, not his death, and there’s so much to enjoy about his life and our life together.” His memoir, plus the documentary and the 40th anniversary rereleases, “bring back those very intimate personal moments that you share. I think for everyone who has had a best friend, when you look back, there’s an intimacy and a bond that you just don’t get in relationships you make later in life, apart from one’s partner, perhaps. So yes, it’s a great loss.”

In 1990, Ridgeley released a solo album, but hadn’t really wanted to – he wanted to do a single first to see how it landed – and it was disappointing. “It was misjudged,” he says. Ridgeley left the spotlight, having achieved his life’s ambitions in his early 20s, living off Wham! royalties. There is something winningly youthful about him and the way he has spent his life – cycling, surfing, walking, a brief stint as a racing-car driver. He didn’t have children, although he helped to raise his stepson, during a long relationship with fellow 80s popstar Keren Woodward, of Bananarama.

“I’ve been very privileged to do exactly as I pleased,” he acknowledges. “My father probably said to me, you can’t be doing exactly as you please all the time, you have to have goals and ambitions, otherwise you can just be wandering. I think I may have achieved other things had I chosen to stick at it, but I didn’t have to, and so I didn’t.” There is something refreshing, or contrarian, in a culture that values relentless productivity, goals and achievement, to meet someone – admittedly financially able – who has spent his life doing exactly what he wants. He laughs. “Well, that’s certainly true.”