As a Māori and a documentary photographer, I often seek out images of our people from the past. I ask myself: what has been captured? When I read that the Dutch photographer, Ans Westra, had died on Sunday at 86 years old I remembered a book of Westra’s I had bought a few years back from a second hand shop. I couldn’t believe my luck when I found it.

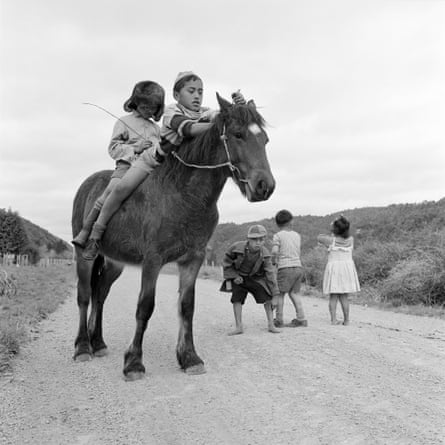

The book, Maori, was published in 1967, a decade after Westra immigrated to Aotearoa New Zealand, where she became one of this country’s best-known photographers. It’s an absolutely amazing collection of images of Māori people with chapters called Childhood, A New Family, Hui, Tangi and Te Atatu Hou (The New Dawn) among others.

It would have been published not long after her then – and still now – controversial work, Washday at the Pa, was printed by New Zealand’s Education Department in 1967 and distributed to schools. The book depicts a day in the life of a rural Māori family with eight children and remains Westra’s best-known work.

Critics, including the Māori Women’s Welfare League, were scathing of Westra’s images, feeling they reinforced stereotypes of Māori living rurally and primitively, happily poor. At the time, Māori widely faced racism and discrimination in employment and public life, and attempts to erase language and culture were starting to bite.

Westra was also a white foreigner looking into a culture that wasn’t hers. Objections to the book led the Education Ministry to recall every copy (it was republished for the first time in 2011).

Westra spent time and had access to her subjects. She lived for five months among rural Māori before publishing Washday at the Pa. She was able to capture images that not only told stories but had deep emotion and connection. Her depiction of an impoverished family also raised issues around the quality of housing for Māori. Washday at the Pa showed how some Māori were living rurally in the 1960s; while things were improving, there remained whānau (families) still living in substandard conditions.

-

Mongrel mob convention, 1982 (left). Coronation celebrations, Turangawaewae Marae, Ngaruawahia, 1963.

Some of the images from Maori, the book I found, let us see into a world that was in a state of flux for Māori. Many still lived on their traditional rural lands but at the time Westra’s book was published, they were moving into the cities, lured by work and the idea of a “better life”, like many of my tūpuna (ancestors). That movement would change everything: over time, some ties were severed to traditional lands and the knowledge of tikanga or sacred rites was lost.

It struck me that if Westra’s images were taken in the mid-1960s then some of the elders in them may have been born a mere few generations away from pre-contact Māori and kōrero tuku iho – handed-down stories. That is what makes Westra’s work intriguing to me. It depicts our old people in an era of change and the images enable me to see and feel those times.

-

Drying eels, Ringatu meeting, Ruatoki, 1963.

The chapter called Tangi has Westra’s camera trained on Māori funeral rituals of old: candid images of kuia (older women) chatting at a marae, kete or flax bag in hand, catching up, deep in conversation. Another shows a tūpāpaku or a deceased person’s body lying on the mahau (porch) of a marae, a sacred meeting place for Māori. The images transplant to a different time but also remind us Māori of the tikanga – correct way of doing things – is something that is constant, learned and held on to from those that have passed, through to now.

Where do the thousands of images that Westra took belong? The National Library of New Zealand has digitised over 150,000 of her negatives and by all accounts are still going. The task is huge and questions will no doubt surface. What say should the whānau of those photographed have in all of this? Do Westra’s images belong in their marae?

In present-day Aotearoa, questions of whose lens depicts Māori and how our stories are framed and told are widely discussed. It is difficult to imagine the publication of books like Westra’s now – especially by a government agency – and that has no doubt prompted the complicated feelings some have about her work.

What Westra did do is spend time, and she had access. That access translates to the thousands of photos of Māori, stories, moments captured by the click of her shutter. For me, they are images to treasure, images to pore over.

-

Cornell Tukiri (Ngaati Hikairo, Ngaati Whaawhaakia, Kāi Tahu) is a photojournalist and writer based in Tāmaki Makaurau