Aras Amiri has kept a low profile since she was released from Iranian detention two years ago, avoiding interview requests after returning to the UK. But now, the British Council employee, who spent three years in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison, wants to speak. An injustice has compelled her: the detention of seven friends and environmentalists she left behind.

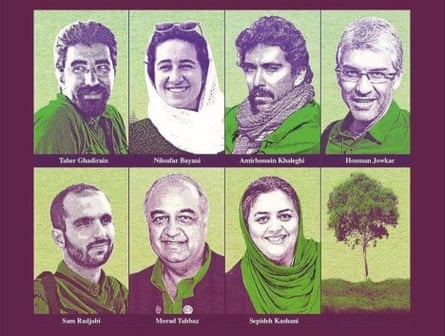

Kept in solitary confinement for 69 days, Amiri was allowed to return to Britain after serving just under a third of a 10-year prison sentence. In the women’s ward, she not only met fellow British-Iranian Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, but Niloufar Bayani and Sepideh Kashani, two of the seven members of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation in jail since 2018. Of the nine originally jailed, one has been released after serving his two-year sentence and another, the founder of the group, Kavous Seyed Emami, died in his prison cell only two weeks after his arrest. The authorities called it suicide, but produced no autopsy.

Amiri said she had previously turned down interview requests because she finds newspaper framing of Iranian prisoners reductionist and populist. But the only crime of her environmentalist friends, she said, had been to try to save nature from extinction.

“They are so close to my heart,” she said. “Can you imagine these people were always under the sky and now, for such a long time, being in a confined space? Lack of freedom is very difficult for anyone, but maybe for those that are used to living in nature, it is made harder.”

Amiri said she learned about Iran’s environment and wildlife through conversations with them in prison, where they held informal workshops for the detainees. “They made prison a better place just by their presence,” she said.

“They always taught if you want to do conservation in a sustainable way, you need local people to trust you so that they continue to support the work, and that applies to conserving the Asiatic cheetah, or dolphins in Qeshm Island, or wild sheep in Larestan, or the Iranian leopard in Golestan national park,” said Amiri. “What makes it more appalling is that the more their imprisonment is prolonged, the greater there is an irreversible loss for Iran’s wildlife, and Iran’s wildlife is also the world’s wildlife.”

For World Environment Day on 5 June, Amiri has helped organise an event at which leading environmentalists will pay tribute to the importance of the group’s work, and again call for their release.

Dr Christian Walzer, now director of health at the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York, who has worked with members of the Iranian group since 2007, said they were “really instrumental” in work to get the near-extinct Asiatic cheetahs defined as a distinct subspecies and to get collars on the animals to track their movement across huge areas.

Unfenced roads, drought, the decreasing population of the prey species, and habitat loss have all led to the decline to as few as 12 Asiatic cheetahs, although Walzer said the precise data was unclear. In March, a female cheetah pregnant with three cubs was killed by a car. Walzer said since the group’s arrest, international cooperation with Iran had withered.

Asked why this group was targeted, he said: “It is incomprehensible. … Putting up camera traps [treated as espionage by their accusers] is standard practice all over the world. We might talk about politics, but just as normal chit-chat. They would talk about rock climbing or fixing Land Cruisers so we could chase animals.”

If there was anything distinctive about the group, it was that some members, such as Morad Tahbaz, a British-Iranian-American trinational, had international connections.

Asked why they were arrested, Amiri said: “Everyone has their own reading. Often stopping the exploitation of nature conflicts with those in power, including governments and big corporations. This is true in Iran and elsewhere … It is hard to find a direct logic. Sometimes it can be random: perhaps it is to create fear.”

But Amiri cannot understand why the group has been treated so harshly, even by the standards of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Two weeks of solitary confinement is difficult, she knows from her own experience, so two years is unimaginable. One of the prisoners, Bayani, sent a letter detailing the interrogation techniques used against her, including sexual threats and warnings that she would end up dead.

Amiri was arrested after she had flown to see her grandmother, who was in a coma in Tehran. She was charged with forming a group to subvert the regime. She said all her work at the British Council had focused on fostering knowledge of Iranian art and artists in the UK. “It was transparent, and agreed with the foreign ministry.” Despite living in the UK since the late 80s, she had an Iranian passport, and chose not to campaign for her release in the UK, hoping discreet lobbying by her family would make the judiciary grant her appeal.

“The principle for me was not to collaborate if I could tolerate the pressure. It is hard if the threats are to your life and people that you know and love,” she said. “The interrogators know their job very well.”