Beneath the glistening water surrounding Albert Dock in Liverpool, there lies a dark and tumultuous history. But today, beside this water, the sun cascades down on diners, seagulls and a carousel outside Tate Liverpool. Ugo Rondinone’s sculpture of rocks painted in rainbow colours stack up high in a celebratory fanfare. But on entering the first space dedicated to the Liverpool Biennial, darkness and silence descends. The contrast between the festivities outside and the reverence commanded by Torkwase Dyson’s three intimidating structures is breathtaking. Each weighing 750kg, the huge, curved sculptures appear as ships ready to make a voyage. The works stand close to what was Britain’s first commercial wet dock, constructed in 1715 to facilitate the transatlantic slave trade.

Slavery – or the impact of colonialism – is central to the work in this year’s Liverpool Biennial, which spans eight exhibition venues and five outdoor works. Entitled uMoya: The Sacred Return of Lost Things, it is as much about the horrors of the past as it is about the healing potential of the future. “uMoya” is an isiZulu word that means spirit, soul, breath, air, wind, temper and climate. For this biennial of 35 artists, it refers to the strong winds of Liverpool that made it central to the slave trade but could now be utilised to forge new, healing paths. Curator Khanyisile Mbongwa explains, in the biennial guide, that she is developing a space “to create openings that allow us to imagine our way through the wound, to clear pathways so that we can hold each other with something other than pain.”

That is not to say that pain is shirked. The full horror of enslaving and oppressing entire communities is meticulously detailed. In Tobacco Warehouse, Isa do Rosário paints tiny black figures on fabric to memorialise bodies lost to the sea, while Binta Diaw uses soil to recreate the plan of the Brooks slave ship almost to scale. The plan was used by abolitionists to depict the horrors of slavery, and when enlarged to this size it is devastating. The thin channels forged between each mound of soil capture how torturously uncomfortable the ship would have been, with no space at all to manoeuvre. Within the soil, Diaw has planted seeds and the small shoots now lean towards the light as a reminder of the humans trapped in its dark hull, desperate for freedom. A recording of M NourbeSe Philip’s poem Zong! repeats the line “the truth is”. The truth is people were tortured, murdered, and displaced. The smell of soil crawls up my nostrils, I can’t escape it.

Equally shocking is Albert Ibokwe Khoza’s The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu, which exposes the practice of ethnological expositions, such as human zoos and exhibitions. In Tobacco Warehouse are the remnants of a performance that took place the day before. It is deeply disquieting: there are hats with cable ties sticking out, a whip flung over a clothes rail, monkey masks with sharp teeth, a pot of salt and a pile of sand, rubbish and bones with footprints around the edge. Even the soft tutus with their gentle feathering become unsettling hung from the ceiling like dead bodies. Apparently, the performance involved Khoza picking people out of the audience at random to wear the masks and dance while the artist cracked a whip. The thought of the humiliation fills me with dread, but it’s nothing compared to what generations of Black people endured.

The unnerving sensation of being watched continues in Nicholas Galanin’s series of masks in St John’s Gardens. Seven upturned baskets with eyes and mouths stand on plinths echoing the monuments in the surrounding area, many of which honour those who made their wealth in the shipping trade. The eyes of Galanin’s faces find them and hold them to account. Upstairs at the Tate, meanwhile, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum casts the audience as watcher. The artist appears on a projection playing seven different female characters, opposite a painting of stern-looking, white Victorians and several church pews for us to sit on. I become enraptured by the characters’ clothing and the woman in the hat shuffling with something in the back corner. I am not stern, but my prying eyes still make a spectacle of the women.

At the Tate, the works of 11 artists focus on moving past catastrophes to search for new futures. A particular highlight is Guadalupe Maravilla’s Disease Thrower series – two towering sculptures that double as headdresses. They are made from steel, gong, wood, cotton, glue, plastic, loofah and found objects Maravilla collected when he retraced his migration route from El Salvador to the US, having originally arrived alone aged eight to escape civil war. In his mid-30s, Maravilla was diagnosed with colon cancer, so in among the natural hues of wood, feathers and cotton, are brightly coloured plastic anatomical replicas. The artworks are used in healing rituals centred on non-western, alternative medicines. In this way, the artist transforms his trauma into empowerment.

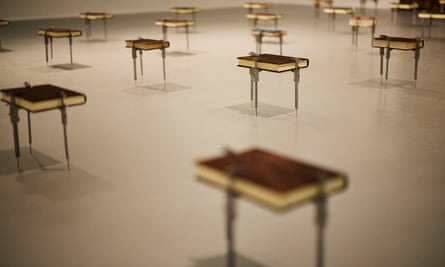

Francis Offman’s exquisite installation of books and callipers manages to balance the terror of the Rwandan genocide with the connection the artist still feels to his home country. As stands for the books, the callipers initially appear benign – but they were the instruments used by Belgian colonisers to measure facial features to segregate communities into racial groups. In contrast, each book is wrapped in repurposed coffee grounds, a major export of Rwanda and something generally regarded as pleasurable. The two contradictory ideas illustrate how, in acknowledging both light and dark, it is possible to move into a more honest and restorative position.

after newsletter promotion

Mbongwa’s curation excels in its ability to hold together a broad theme across the biennial while allowing each gallery to engage with a dialogue of its own. Bluecoat is the most joyous, opening with a video work by Galanin where the narrator tells a child “I love you” and “You’re doing such a good job”. Presented in the Lingít language, spoken by the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific north-west coast of North America, the heartwarming film shows the child glowing under the compliments and celebrates marginalised languages. Kent Chan’s film delves into the archives of the World Museum, imagining a dialogue between works of tropical provenance from the global cultures collection. The pieces bicker over the difference between being an artefact and artwork. A mask boasts: “I used to possess people.” It is amusing but also raises valid questions about the storage and ownership of works from other countries.

At FACT, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński’s Respire (Liverpool) comes up with a suggestion to deal with the burden of the past – and it is remarkably easy. It just involves breathing. In a dark room, large projections feature participants from Liverpool blowing up a bright red balloon. The sound of their breathing, a gentle choral hum, and the lines “Keep on keepin’ on” float through the space. In the centre is a cushioned bench with three seats, surrounding a vibrating pool of water. Sitting alongside strangers in this meditative space, Kazeem-Kamiński makes it clear that true progress requires breathing with others. Healing is a communal activity.