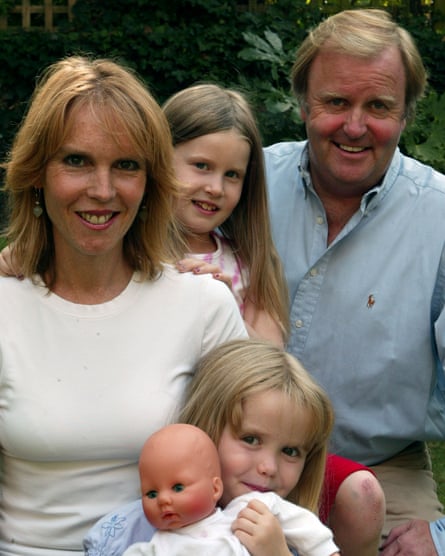

When my mother died in 2010 at the age of 52, she left behind two teenage daughters, a devoted husband, innumerable friends and an archive of beautifully written diaries chronicling nearly every year of her life from the age of 25 until her final days. My sister and I were aware of this growing collection throughout our childhood; her past selves were stacked neatly at the bottom of the living room bookcase, preserved in their various jackets of worn leather or patterned fabrics. “These diaries have been the only constant ritual of my life,” one entry reads. “After writing, I feel immediately better.” Convinced of the psychological benefits, she encouraged my sister and me to take up the habit. When I was seven, she bought me a miniature copy of the book she was filling at the time. It was a magnificent object composed of thick cream parchment, soft Italian suede and an impractically long tie that was always dangling out of my school bag, trailing in puddles or dripping in orange juice. We wrote in our matching books together in the evening, before bed. It was the only diary I ever managed to fill cover to cover.

Some writers are natural diarists. I am not one of them. As a child, I was far more interested in writing stories, disappearing into the lives and minds of others. I see now that this stems, in part, from an early distrust of my own voice, which struck me as so irregular, so various and so utterly contradictory that I believed it genuinely dangerous; the first person was a tool to be wielded only with the utmost caution. It is still only under the guise of fiction that I feel I can travel confidently towards any kind of authentic truth. But for my mother – a documentary maker for much of her life – it was effortless.

It didn’t take long after she died for me to start tentatively dipping into these texts. I was desperate to feel her near, to collapse time, to communicate in some way with the person I loved and needed most in the world, who had quite suddenly vanished. I worked my way back through her last months alive, the fragments of her final observations growing into longer, more coherent sentences as her body grew stronger. I followed her across hospital waiting rooms and parks and parties, relishing in intimate snapshots of our closeness, horrified by the monstrous portraits of my teenage petulance: “She [ie me] is so desperate for drama,” she writes, “she is incapable of seeing there is one happening right under her nose.” It was cathartic, revealing and, at times, deeply painful. She used to tell us that reading a loved one’s diary was one of the worst things you could do, to yourself and to its author. I wondered often what she would make of my invading her privacy like this.

And then, deep into the “splendid, balmy July” of 2002 (her time), December 2012 (mine), I found my answer. “I have never had to think about an audience for my writing,” the entry began. I felt a sudden chill spread through me. “Having said that, Maddie, if you’re reading this now, I do hope you’re enjoying it […]” For a moment, I could hardly breathe. It was as if she sensed me lurking there, and had turned and stared straight at me. “And stop biting your nails!” she added. I remember laughing hysterically with relief (she knew!), clutching the book to my chest (she knew). I was six at the time of this entry. Her cancer had just returned for the second time. My nails and the skin around them were, as she guessed, still bitten raw. But what this breaking of the fourth wall had done was give me the sense that she was not only permitting me to be there, or challenging me to follow her, but that she had, somehow, been writing these sacred texts for me, all along, and that it must be my responsibility, now, to become their sole scholar, audience and archivist.

And so this is what I did. I pored over each one, reliving my childhood from her perspective, finding my own memories hiding in the pockets of hers. I delighted in being able to chart the development of mine and my sister’s characters from birth (“Maddie always her best at a party”, “Bella always trying to get her toes crushed by moving vehicles”). I was not blind to the somewhat narcissistic nature of all this, and she was so excellent a mother I often had to stop to wonder if I was, indeed, some sort of child prodigy. But the older I got, the more interested I became in the earlier diaries, in getting to know the person before/around/within the mother. I studied her process as she wrote novels and columns, directed a feature film, worked as a researcher for London Weekend Television and lured an interview-shy Harrison Ford across the Atlantic with the promise of personally delivered bagels. (“He was charming, tired, kind.”) She was impressive in big and small ways. There was a surprisingly buoyant account of the week she was kidnapped in India, and a brilliantly observed few months spent in Bosnia during the war, where she was making a documentary for the BBC with the Red Cross. And yet for all this “plot” and drama, I still believe the best thing about them to be how unashamedly romantic they are.

The diaries from her late 20s and early 30s, in particular, are fizzing with a very pure sort of passion. Pure, in the most literal sense, in that they are full of deeply romantic interactions that are left unconsummated: a brief conversation over a joint with a sculptor at a friend’s wedding contains all the repressed longing of the scene in which Wentworth helps Anne into the carriage in Persuasion (her favourite Austen novel). A meal in Chinatown followed by a walk around Green Park with a cameraman has the giddy innocence of Paul Newman and Katharine Ross’s bicycle scene in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (one of the first films we watched together). It was impossible for me, as both reader and daughter, not to be enraptured; impossible not to fall in love with the romantic heroes and antiheroes peppered across these texts; impossible not to have favourite recurring characters I rooted for and missed madly when they vanished from the pages. Her life story unfolded before me like the greatest work of extended fiction, only one I had a vested interest in because it was my creation story. The diaries were becoming more than places I could retreat into in order to feel her near; they were my scriptures, and I was convinced they contained the secrets – the instructions – to a full and good and interesting life.

after newsletter promotion

But the problems I started to run into were those faced by anyone looking to extract truth and meaning from text. My mother was no longer around to explain herself, yet she had obtained godlike status; her word was gospel. As a student, after being sick from too much drinking the night before, I would scour the diaries desperately in hope of absolution. Once, I found the words “I ache from excess” and felt immediately placated. She did this too, I would tell myself, sliding on my coat and making my weary way back out to the pub; it’s fine. She did this too. There were people in my life I ended up falling out with, provoked by observations she had made about them. A few years later, I found myself in a consuming relationship of uncanny similarity to one she had been in at the same age; both men had night terrors that played out almost identically, and I would lie there in the dark, repeating the same soothing phrases that she once had, wondering if these parallels were mere coincidences or my design. I could see, suddenly, how easy it was for “believers” to relinquish responsibility, to let their holy books carry the burden, to read selectively and lazily. Fundamentalism, of any kind, is a dangerous thing.

It soon became clear that my obsession with these diaries was as much about my need for control, for answers and meaning, as it was about remembering her as a mother, or getting to know her as a woman. Slowly but surely, I had to wean myself off them, or change the way I used them, at least. I had to allow myself to be disappointed and disgusted by her the same way I could be with myself, to humanise the woman who had become my moral compass. I was surprised to find that by recognising her flaws – her competitiveness, her occasional vanity, her hopeless romanticism – I started to forgive these qualities in myself and love her all the more.

I like to think I have a much healthier relationship with these diaries now. Though I do not return to them nearly as often as I used to, they still feel like her way of mothering me from beyond the grave. I have never felt this more than I did a few weeks ago, when moving out of the flat I had lived in for three years. I had just left a loving and healthy six-year relationship for reasons I am still not entirely sure of. Half of my life lay around me in boxes. I felt remarkably lost and alone and had the sudden urge to find that first (and last) diary I ever wrote, at seven years old – the magnificent suede cover, the crusty juice-soaked tie. I searched desperately through the boxes and bags, ripping them apart, with no luck. I could not remember the last time I had seen it, and I knew it was gone, in that intuitive way one does with certain missing things, when their lack feels palpable and the space around you seems to open its palms, as if to say: it isn’t here. I curled up on the floor of this new, empty, unfamiliar flat, and cried. I cried for my own carelessness, the exact carelessness that means I lose at least one very valuable possession a month and don’t pay my taxes on time. I cried for the crushing realisation that sometimes humans break things just to see if they can. And then I saw the box of her diaries – the only possessions I have ever managed to keep safe and organised. I pulled one out at random.It was battered, with a green marbled cover, the spine falling apart. It opened in the middle of 1981, and I began to read an entry that bore a striking resemblance to my current situation.

My mum had just broken up with one of the great loves of her life, and had found herself alone for the first time in six years (six!) in a new flat, unable to sleep due to “scratching sounds coming from the kitchen”. What followed was a scene that involved her constructing a mouse trap out of loo rolls and ginger nut biscuits, screaming at the mouse, gently trying to reason with the mouse, desperately attempting to sheepdog the mouse out of the flat – all, of course, to no avail. She gave up eventually, and went to sit on the floor by her dishwasher, where the mouse had made its home. They shared the last of the ginger nuts. “I have never felt so grateful to anything,” she writes, “for refusing to leave me alone.” The whole thing was sweet and symbolic enough to make a good little short film, and I laughed as I read it; I laughed through streaming tears, and felt the kind of exhausted but glorious relief that comes with the acknowledgment of true despair, for it was both more and less than a remembering. It was the privilege of getting to witness her as a young woman – this funny, flawed, familiar voice – reaching out, across time, and being there for me the only way she could. On our first nights alone in our new homes, 40 years and five miles apart, she had the stubborn mouse for company, and I had her. I pressed my hands on the pages where hers had been. I felt I would never know true loneliness, for her absence in my life had rendered her eternally present. I turned the page, and there, filling up the whole sheet with black marker pen, were the words: “be brave, be brave, be brave”.

One of the great tragedies of losing a parent as a child is the knowledge that you will, inevitably, begin to forget them. For many years after my mother died, I remember desperately trying to conjure the sound of my name in her voice as much as I could – her smell, the feeling of her hands on my face. Her breath on the top of my head. I feared the time would come when the “idea” of her, like the ship of Theseus, was a reconstructed fiction. The existence of her diaries and the “story” of her life has done something to prevent this, I think. Of course, it is not the same – it is never enough. There is no amount of reading or writing that can bring her back. But literature reminds us that, even alive, we exist only in the imagination of others. We can never really know another person, let alone our many selves. And though the diaries fail to represent exactly who she was, to me, through them, she lives anew; suspended in time and yet evolving, constantly, in the space between where a life stops and a text begins. So that when I fear I have forgotten her almost entirely, I know I need only pluck out a dairy, turn the page, and there she is: this miraculous collusion of myth and mother, near and far, absence and presence. For a second, I feel her everywhere. The moment passes. She slips away. And I go on, as we must, changed.