“If you’re going to kill me, then kill me. But I’ll tell you up front: you won’t silence me.” In a 37-minute Facebook Live broadcast on 21 July 2022, the independent Colombian journalist Rafael Moreno defied his detractors – and predicted his own death.

In the recording, Moreno denounces alleged corruption in the surrounding region of Córdoba, one of the poorest and most violent parts of the country, and a strategic corridor for drug smuggling.

He recites a litany of accusations: inflated contracts, unfinished public works, embezzlement. “They’re stealing,” he claims. “Somebody has to point out the corruption in this region.”

In his reporting – which he published on two Facebook pages – Moreno spared no one, from powerful local politicians and mining companies to paramilitary groups and other journalists.

And his accusations seemingly did not go unnoticed.

In the video, Moreno reads out a note he had recently found on his motorbike – alongside a bullet. “We know all your movements: where you go, when you wake up, when you go to sleep … We know everything about you and we are not going to forgive you.”

Like many local reporters in Latin America, Moreno was unable to make a living from his journalism, and had recently opened a grill and car wash in the town of Montelíbano.

Three months after posting the video, on 16 October, he was closing the bar when a man wearing a baseball cap entered the restaurant, pulled out a revolver and shot him three times.

Moreno died immediately. But thanks to the documents he left behind, he was not silenced.

Days before his assassination, Moreno had contacted Forbidden Stories, the French nonprofit whose mission is to pursue the work of assassinated, threatened or jailed reporters. He joined the SafeBox Network, which allows threatened journalists to upload sensitive information for safekeeping, and he started sharing his findings.

After his death, a consortium of reporters from around the world came together to continue Moreno’s work. They analysed hundreds of documents, emails and public contracts obtained through freedom of information requests.

Together with on-the-ground reporting and interviews with dozens of sources, they explored his claims of a system of clientelism in the province of Córdoba in which several million dollars were allegedly embezzled.

Q&A

What is the Rafael Project?

Show

The Rafael Project was launched in October 2022, days after the murder of Rafael Moreno, an investigative journalist based in Montelíbano, Colombia.

A few days before he was killed, Rafael told Forbidden Stories that if anything were to happen to him, he wanted his investigations to be pursued and published worldwide.

For six months, 30 journalists coordinated by the French nonprofit Forbidden Stories have pursued Moreno’s leads to keep his investigations alive.

This project is being published by 32 media organizations and sends a clear message to the enemies of the free press, not only in Colombia but around the world: killing a journalist won’t kill the story.

The team also examined three mines in the region, confirming many of the allegations Moreno had made, including environmental damage, failures to consult with Indigenous communities and non-licensed operations.

Today the Guardian joins 31 media partners around the world to publish the consortium’s work – and highlight the investigations that may have cost Rafael Moreno his life.

‘Anybody could have killed him’

Between 1992 and 2022, 95 journalists have been killed in Colombia, many of them caught in the crossfire of a brutal civil conflict between leftwing guerrillas, rightwing paramilitaries and state forces.

A series of peace deals removed many of the conflict’s factions from the battlefield, but new criminal groups have sprung up, and the country’s reporters are often most at risk when investigating drug trafficking, local politics and corruption.

According to his friends and family, Moreno was relentless in his pursuit of alleged corruption. “He was constantly throwing banana skins,” said Rafael Martínez, cabinet secretary of the nearby town of Puerto Libertador, and a longtime friend. “Anybody could have killed him.”

His last investigation focused on accusations of environmental crimes in the basin of the Uré River. Moreno had discovered that someone was using a backhoe and heavy trucks to systematically strip sand from a river beach for use in public construction works.

The beach sits next to a national park and inside a protected area, and Moreno alleged that the project did not have an environmental licence. He also claimed the scheme was linked to one of the most powerful political dynasties in the region: the Calle family.

Gabriel Calle, the family patriarch, is a former regional deputy and mayor of Montelíbano currently under investigation for several offences, including irregularities in drawing up contracts and illicit enrichment. He denies the charges.

In the 10 days before his murder, Moreno had submitted four freedom of information requests, including one requesting documents about the Uré River. The response came two days after his death.

In an interview with the consortium, Calle denied all responsibility for the sand extraction, and said the trucks were on a public road, although the land registry does not mention any public road in this location.

He denied having any involvement in or knowledge of Moreno’s death. “I had a good friendship with Rafael – we never even had an argument. I wasn’t worried about what he said because it wasn’t true,” he told the consortium.

Moreno’s new career: investigative journalist

Moreno was born in the village of Puerto Libertador, and after leaving school at 15 worked in a gold mine, picked coca leaves and completed his military service.

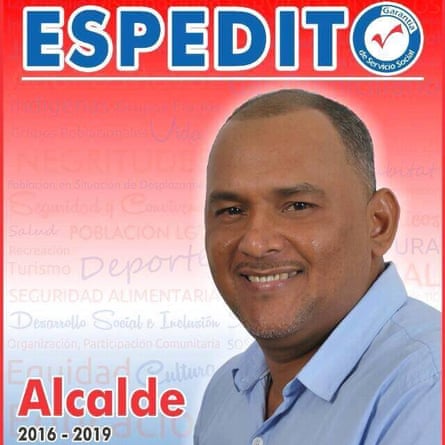

When he returned to the region aged 20, he met Espedito Duque, a charismatic upcoming politician, and went to work for his mayoral election campaign in Puerto Libertador.

“Rafael was his right-hand man, he was practically his head of communications,” said Moreno’s sister, Maira.

After two failed attempts, Duque was elected in 2015, and Moreno went to work for the new mayor. But people close to Moreno say that he was becoming disillusioned with his political mentor.

Moreno felt that the changes Duque had promised were slow to arrive, and he believed the mayor relied on the same allegedly corrupt functionaries who had served past administrations.

After the peace deal between the Colombian government and leftwing Farc rebels, public money had become more easily accessible in areas like Puerto Libertador which had been were particularly hard hit by the decades-long conflict.

Since 2016, more than $100m has been invested in the five municipalities that make up the region. The resources were earmarked for more than 130 public works projects, including road repairs, education and healthcare, as well as housing and energy infrastructure.

But activists say many projects were never completed. “Many of these works were unfinished or not even started,” said Enyer Nieves Pinto, president of a civil oversight group in the region.

So in December 2018, Moreno launched a new career as an investigative journalist.

His method was simple: he would log on to a government website listing public contracts, download the documents, pore over the budgets and proposals, and then visit the location to see if the work had been carried out. He published the results on his two Facebook pages: “Rafael Moreno Investigator” and “Voices of Córdoba”.

One case involved the renovation of the municipal stadium in Puerto Libertador, which – despite a budget of more than $1m – was abandoned unfinished.

In a poor region still haunted by decades of violence, many locals were revolted by allegations that money had gone astray.

But Moreno’s reporting also led to threats from local crime factions which routinely take a cut from public budgets. In 2019, he was named as a “military target” by one gang; in 2021, he was briefly kidnapped by the country’s most powerful crime group, the Gulf Clan.

Moreno regularly shared these threats with the National Protection Unit, which provides countermeasures including panic buttons, armoured vehicles and bodyguards to threatened activists and reporters. But the protection he received was irregular, and he had none on the day of his murder.

Still, Moreno continued to publish articles and submit legal complaints and freedom of information requests.

The consortium partners were able to consult Moreno’s email, where among the thousands of emails and attachments, they discovered a formal complaint Moreno filed on 5 January 2021 against Duque and his associates, alleging “acts of corruption, embezzlement of public funds, influence trafficking and clientelism”.

The 21-page document alleges that Duque’s close friends and family set up dozens of NGOs which then won contracts to “facilitate the appropriation of public resources”.

The document never received an official response. But an analysis by the Colombian investigative outlet Cuestión Pública and the Latin American Investigative Journalism Centre (Clip) shows that between 2016 and 2022, the Duque administration and its successor appear to have signed 99 contracts with 13 people close to the mayor’s family – contracts worth a combined $3m.

Many of the contracts were awarded by mutual agreement, meaning they were never offered for public tender.

In a statement to the consortium, Duque denied all accusations of wrongdoing, saying that the allegations of corruption were “absolutely false” and adding: “It is untrue that I supported the creation of entities to benefit from contracts with the municipality.”

Duque said: “[Moreno’s] accusations were due to resentment, but all my actions [in office] took place in public, and any complaints were examined by control bodies.”

He strongly denied any involvement in or knowledge of Moreno’s death, saying: “I swear by God and my family that I had nothing to do with the assassination of Rafael Moreno, and I need you to keep investigating that cruel murder until you get to the truth. Because on the day of his murder the politicians who were supposedly his friends didn’t cry, they celebrated and toasted in the street, and put the blame on me and my family.”

He added: “May he rest in peace. His passing caused me great pain.”

Threats, murder and journalists going quiet

Up until his death, Moreno kept posting updates on his Facebook pages, building up his allegations of corruption and clientelism. He was also investigating an alleged rape case implicating the son of a powerful local figure.

But the threats were also gathering pace, and on the night of 16 October 2022, he was shot dead.

Since then, other reporters in the region have stepped back from investigations. Yamir Pico, Moreno’s cousin and fellow journalist, temporarily closed down his media outlet in November after receiving threats. He later restarted it but said he would not pursue any more investigations. Another local journalist has decided to focus on sports and cultural coverage. A third has left the region and is currently in hiding.

More than six months after Moreno’s death, nobody has been arrested in the murder case. Duque is planning to run for mayor again this October.

Reporting by Paloma Dupont de Dinechin (Forbidden Stories), Andrea Rincón (Cuestión Pública), Edier Buitrago (Cuestión Pública), Claudia Duque (freelance), Juan Diego Quesada (El País), Felipe Morales (El Espectador) and Ivonne Rodríguez (Clip)