It is 7.57am on a Monday morning. I see Christian Cooper sitting with perfect posture on a bench right at the entrance of Central Park at West 103rd street. His first question for me is: have I brought any binoculars? I don’t own a pair, I admit. No worries, he says. If we spot anything, he’ll lend me his. That’s the most important birding tip I learned from his new book: you spot movement in the sky, with your naked eye first, then you raise your binoculars, not the other way around. Cooper is joyous when he tells me this. “If the book does nothing else but teach people how to use binoculars so they can actually see the birds, mission accomplished,” he says.

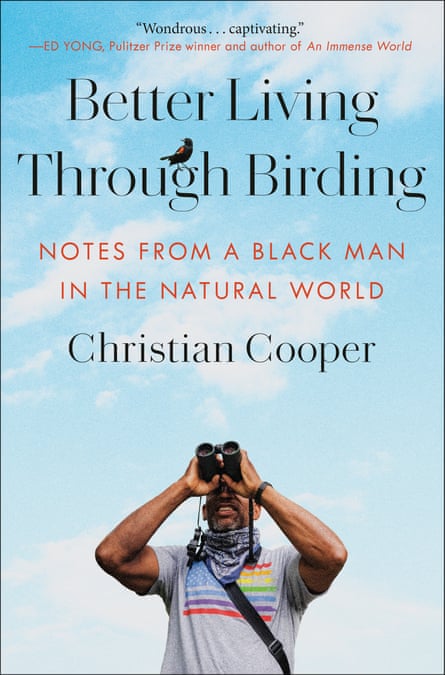

The book, Better Living Through Birding, is Cooper’s first memoir. It traces his journey from his childhood as a nerdy kid from Long Island, to his time as a comic book editor, to his birding days in Central Park. While doing so it weaves the history of Black people in America – from slavery and lynchings to segregation and economic disparity – into the unfolding of his life.

It also covers the moment, three years ago, when Cooper received international attention when, while birdwatching in Central Park, he asked a woman to leash her dog, in compliance with park rules, because he didn’t want it to disturb or maim any nearby birds. The woman, Amy Cooper (a stranger to Christian, their shared surname a coincidence), who is white, became irate and said that she would call the cops and tell them that an African American man was threatening her life. Christian Cooper was doing no such thing, but he did film the entire exchange.

He posted the video to his Facebook friends with the context of what happened. His sister Melody asked if she could share it on Twitter. Cooper hesitated but ultimately obliged. Kathy Griffin retweeted him and the rest, as they say, is history. The 69-second video got more than 45m views. Cooper now references this whole ordeal as “the incident”.

In that instant, a white woman made a false accusation that could have led to his death. She knew the stakes, which is why she feigned hysteria on the phone with the cops. Christian Cooper knew the stakes, too. But though Amy Cooper swiftly lost her job after the video went viral, Christian Cooper did not want any part of the prosecutorial process, a decision that put him at odds with some Black people, including his relatives. He tells me: “There were a lot of factors involved. It was potentially very important to set a precedent where someone was held accountable, legally, for making a false accusation against a Black person.” He stresses that it was a tough call not to get involved, but unless the district attorney were to subpoena him, he was going to choose mercy.

Not everyone was a fan of his choice. One of his relatives revealed the reason for their ire: “They had a brother who was in an affair with a white woman and when she got found out, she said it was rape. That person spent years in a jail in the south for that reason. So false accusations have haunted us for a long time,” Cooper says.

I admit to him that, at the time, I was one of those people who was shocked that he didn’t want to be contribute more to her downfall. Punishment along with further punishment is part of what structures – and upholds – our society; we live in a punitive culture and the US has the highest incarceration rate in the world. It would be normal for Cooper to want retribution, but he doesn’t see it that way.

“We [African-Americans] are fighting to have some sense of proportionality in how we are treated in the criminal justice system. So how can I turn that around and not consider the same thing?” he says. Cooper thought that the woman had already received enough punishment without further piling on necessary. “Her life had imploded. It’s not like I had been handcuffed or thrown to the ground or God forbid anything more deadly or serious,” he says. “If you could look at what happened to her and not conclude that you shouldn’t make false accusations, then how is any legal proceeding going to change your mind?”

Furthermore, he says, he is not traumatized. People will approach him and say how sorry they are about his trauma. “What trauma?” Cooper says. “She just does not have that much power. Maybe it’s a consequence of being Black our whole lives.” In this country, Blackness is inextricably linked to suffering. A racist incident can often be the summary, rather than a chapter, of how our entire lives are esteemed, and this is what Cooper resists.

We approach a spot where, about five or six years ago, Cooper spotted a Lincoln’s sparrow; he calls these “the fine wines of birding” because they are so hard to find. “It’s like someone took pen and watercolor and drew a sparrow because it’s so finely marked,” he says. This is what Cooper thinks about when he enters the park. He was neither traumatized nor shellshocked after “the incident”. He tells me: “When I go back to the park and I am at that spot where that mess happened, I’m not thinking about that. I’m remembering that time when there was a mourning warbler on that chip path 15 years ago and I remember the scarlet tanagers last week. That’s what I think about when I’m in the park.”

Today, for example, he’s more excited about whether or not we’ll get to see an Acadian or great crested flycatcher. He’s concerned we might not get lucky because spring migration has already passed and fall migration is still months away. This is a man who routinely wakes up at 4am and ventures into Central Park at 5.30. He lets me know early on that his life and passions are more than “the incident”.

As we start walking we spot a red-winged blackbird. It’s a very significant bird in Cooper’s life, he calls it his “spark bird”, a term used to describe the type of bird that first converts a person to birdwatching. Cooper references the bird at the beginning of the book and it sets the tone for a multilayered and intricate exploration of his own identity.

after newsletter promotion

In his book, Cooper describes the red-winged blackbird as a trickster of sorts. In the Americas, it’s part of a family of birds called icterids. When English settlers came to the western hemisphere, they thought it to be the same as the birds they saw in the UK, thus giving it the same name. But the joke was on them because the Eurasian blackbird is not an icterid, it’s part of the genus thrush. To add even more complexity, the UK already has a bird called the redwing, which belongs to the thrush family as well. Are you confused yet?

Cooper writes in his book that these complicated taxonomies, through which humans label birds, first resonated with him when he was young, as a Black, queer, closeted kid growing up in a conservative Long Island community in the 60s and 70s. Though Cooper knew he was queer from the moment that his five-year-old self saw a male superhero in a comic book, he wasn’t open about his sexuality until he began studying at Harvard, where he took part in the ornithological club and the gay students association.

His love of comics landed him a job as an assistant editor at Marvel in the early 90s. When he talks about this period of his life, I’m astonished by how certain he was in his identity at that time. He tells me that one day Paul Becton, a Black colorist for Marvel, walked into his office and saw a picture of the former Yankees player Steve Sax on the wall. “He was like, ‘Yes! Are you a Yankees fan?’ I’m like, ‘No.’ He’s like, ‘Are you just some homosexual with a thing for Steve Sax?’ ‘Yes,’” Cooper says.

Cooper was only in his late 20s then, at a time when the world of comic book publishing was even more blindingly white than it is today. But he never tried to hide who he was: “I didn’t give them a choice. I’m queer. I’m OK with it. You can either be OK with it or not. That’s on you.”

Cooper’s love of nature initially came from his father, Francis, a Korean war veteran, science teacher and civil rights activist. Francis took Cooper on trips to Yellowstone, Maine, the prairie provinces of Canada and the Olympic peninsula, trips that Cooper found it hard to return to in his writing. “At one point, my editors had to wait a whole month before they got any more pages out of me because I came to the part in telling the story of my family where everybody starts to die. I was like, ‘I cannot write this.’ I didn’t know how to deal with this. I’m not a very confessional person. And I’m not a very emotional person.” In his memoir, he writes that his father was a man who often projected his anger and frustrations on to his family, which made Cooper, his mother and his sister feel as though they were walking on eggshells around him for many years.

The binoculars that hang around Cooper’s neck are the pair his father gifted to him on his 50th birthday. Even if it might have been hard for Cooper to write about and memorialize his father, his father was with us on our walk.

Activism is also in Cooper’s blood. There is a photo of him as an infant in a stroller during a protest. Whether it was fighting school segregation or spearheading a Long Island chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, Cooper’s parents phoned, marched, organized and did whatever else they could to get into “good trouble”, a phrase most popularly attributed to John Lewis and his activism efforts.

Cooper was arrested twice in 1999 within a matter of weeks while he was protesting for justice over the murder of Amadou Diallo. After a gay couple was bashed in upper Manhattan, he along with his allies at Glaad, the LGBTQ advocacy organization, organized an anti-violence rally.

Black people and birds are connected particularly because of their shared history with migration, Cooper says: “Birds and African American history – they weave together in surprising ways. My family left Alabama because there was all this opportunity – the great migration. That’s exactly why birds migrate. Birds leave the south to come to the north because of opportunities seasonally.” He gets enthusiastic when I mention that even prior to this turning point in US history, Harriet Tubman learned bird calls in order to signal to other freedom seekers when it was safe or unsafe to proceed. He loves this part of her story.

The silver lining of “the incident” is that Cooper has met many other Black people who’ve gotten interested in birding, which delights him to no end. Months after the incident happened, he did a PBS special in which he talked about the “joys and challenges of birding while Black” and was featured in the Washington Post about his desire to diversify the activity.

Birds have always meant liberation to Cooper. Alongside his memoir, he has a forthcoming National Geographic wildlife show in which he will examine birds across the US, including in his family’s ancestral land of Alabama. He hopes that readers and viewers alike can understand this symbolism. In his own words, as the birds sing above us, “Every place has atmosphere, every place has sky, and they just spread their wings and they can go anywhere. You know, the whole time we’ve been walking and talking, we can walk forward, we can walk back. We can walk left, we can walk right, but we can’t really go up or down very much unless, you know, we’re walking up a hill or down a hill. They just think it and they can go up or down under their own power. That freedom, that ability to think in three dimensions. All of that just makes birds incredibly inspiring.”