We have everything we need: gags, rubber masks, leather, various whippy, stingy, thwacky things, hoists, chains and 100ft of rope. Also: one razor blade, three axes, a rack of gold-plated wire bikinis (fashioned from safety pins), several buttocks, plenty of dicks, a bucket of blood and a load of offal.

There’s Saint Sebastian, pierced by arrows and a paintbrush, and here’s Bob Flanagan, photographed with his balls dragged low by a weight on a chain, with various bits of metalwork piercing his penis, scrotum and nipples. Presenting himself as a BDSM superhero in a cape made from a hospital gown, Flanagan was a sado-masochist performance artist. Working with his dominatrix accomplice and lover Sheree Rose, he turned his cystic fibrosis, constant pain and fortitude into art, transforming suffering into a kind of celebration.

Hardcore has got something for everyone, but the only players having any fun here are painted, sculpted, photographed or drawn. We can look, but we mustn’t touch. A mechanised witches’ broom of leather belts sweeps the concrete floor in Monica Bonvicini’s sculpture. Rather sweep the floor than flail me? A bare foot grinds into a male groin in a painting by Joan Semmel that foot fetishists and aficionados of observational figurative paintings might enjoy. Two muscular beings do something to a third, swaddled figure in a bleak, smudgy grey void in one of Miriam Cahn’s drawings.

Whether we are watching torture or pleasure, the viewer can’t tell. In another of the Swiss artist’s, a woman masturbates and gives us a cartoonish, knowing smile. Stanislava Kovalcikova’s Sebastian, and some of her other forest-dwelling denizens, also acknowledge us while going about their inscrutable and violent business. These looks drag us into a kind of complicity. The more you look, the more Kovalcikova’s enjoyably disturbing paintings reveal, with their mix of the folkloric, religious and mythological.

Doreen Lynette Garner, who also goes by the name King Cobra, presents a tasty meal in a bamboo casket on a mirrored plinth. White Bread is all gristle and guts, with an indigestible intestinal tube running through its cut slices, like the hard-boiled egg in a veal-and-ham pie. I’d have a slice (I’m all for nose-to-tail eating) except the ingredients include resin clay, hair weave, acrylic, silicone and tattoo ink.

Nearby, the artist’s abattoir-fresh butchered animal carcass, suspended like Rembrandt’s ox, glistens with pearls and glass beads among the artificial innards. Silicon-slimy guts pile up on a wood plinth below the carcass, and a hand pokes out from below, clutching a knife. Get down on all fours and you can see the hand is attached to a severed forearm. Maybe there just wasn’t room for a whole body. Unless somebody ate it.

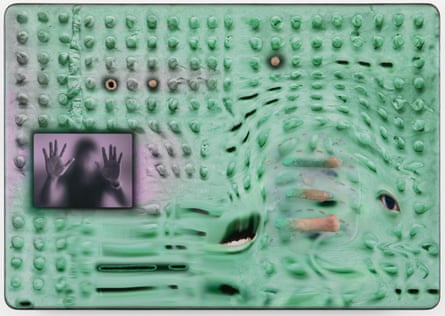

Shaped like a desktop screen, Tishan Hsu’s Double Interface- Green turns the body into a ghost trapped in the machine. Eyes and orifices loom, blur and distort across the nacreous green surface, drowning in the virtual. Pink nipples pucker into 3D relief and raw, bony handles erupt from the painting’s skin, with its scum of pores and little wiry hairs. You could use Hsu’s paintings to warn children about the dangers of spending too much time online, but they’d think you were telling them a hokey old fairytale.

The quietest, most modest work here is a small watercolour depicting a man in a rubber mask with a breathing tube attached. Monica Majoli’s Rubberman is one of many she has made of gay rubber fetishists at play. The thin layers of pooling and bleeding pigment capture a sense of the psychology of enclosure and the anonymity of the figure sweating within their second skin.

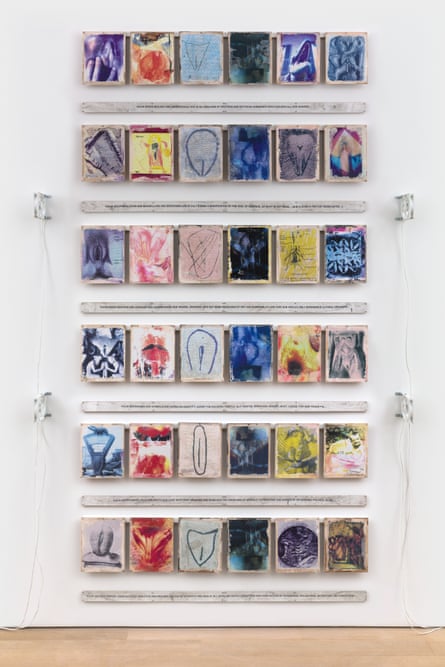

Carolee Schneemann’s 1995 Vulva’s Morphia has lines of text detailing the education of an innocent abroad, Vulva, alongside vulgar sketches of the female sex organs, medical illustrations, fragments of porn and photos of fertility gods and ancient sculptures. Beset by patriarchy, Vulva reads biology and deciphers European intellectuals Lacan and Baudrillard, as well as US sexologists Masters and Johnson.

Furious and funny, Vulva’s Morphia is very much a work of its time. Vulva eventually “runs into the Cedar bar at midnight to frighten the ghosts of De Kooning, Pollock and Kline”. New York’s Cedar Tavern was, in the 1950s, the home from home of hard-drinking macho abstract expressionists, who could have done with some hardcore Schneemann to set them right. Little whirring electric fans mounted on the sides of her work stop this big arrangement of text and images from overheating. Phew.

Meanwhile, the scenes played out with dummies and prosthetics in Cindy Sherman’s untitled sex pictures from 1992 are desperate and theatrical, enlivened by little drools of viscous liquid. With their closeups and cropping, their lighting and odd angles, Sherman orchestrates her photographs like a porn director, staging the extreme. The whole business looks grim and abject, as Sherman intended. But I think she wanted to be funny rather than having any moral purpose.

What once might have been provocative, dangerous or taboo can now appear quaint, cliched, a bit too desperate to be fun. Subcultures are killed by the mainstream and, in any case, we’ve seen too much. From hardcore to no-core, the frisson, you might say, has gone.