At the National Herbarium of New South Wales, specimens of plant species are treated with reverence. They are kept in temperature-controlled sealed vaults, in immaculate condition, behind thick walls of rammed earth that are fire- and waterproof. These plants, after all, are precious: the information that holds the past and the future. As collections manager Hannah McPherson puts it: “They are here for all time.”

When author and academic Prudence Gibson first came to the herbarium, at its old site in the Royal Botanic Garden, she was “changed”. Established in 1853, with 1.4m specimens and 8,000 more coming in each year, the collection is currently worth $280m. The sight of so many plant specimens, Gibson says, was “dizzying”. Last September, the entire collection moved to the Australian Botanic Garden in Mount Annan, where it now resides in a state-of-the-art building.

It was a botanic Nirvana, and Gibson – who studies plants and art at the University of NSW – immediately fell in love. In her new book, The Plant Thieves: Secrets of the Herbarium, she writes: “It is a place of exquisite beauty and holds the seeds and secrets of future life. But it also records the violence and damage done to the earth, the trees, the plants and to the very future it promises to secure.”

Displayed with each specimen at the herbarium is its Latin name, the date of collection and the collector’s name, with field notes about its location. Often handwritten, some can run to the poetic: “windswept cliffs” and “gently undulating red sands”. It’s a sterile, air-locked room designed to banish insects and mould, but it is also redolent with the smell of the Australian bush, and the stories of those collectors – explorers in harsh, inhospitable places, botanists in their boots searching for something special.

“Each specimen represents a point in space and time,” McPherson explains. “For example, collections from the turn of last century from areas which are now built on. That tells us about the history of plants that we can’t see any more.” In fact, the herbarium holds 15 of the 37 species that are listed as extinct in NSW. “We interrogate the collection through time to investigate climate change impacts and what it is doing to the flora – for example, changes to flowering time.”

Gibson’s book, part of a collaboration with the herbarium which received a grant from the Australian Research Council, took her on a three-year odyssey. But the genesis came from an unlikely place: a cacao ceremony and group meditation hosted by a shaman friend. “I was conscious and present but also somewhere else,” she writes; “you could say that cacao led me here, to this project with the herbarium.” It also led her into the underground world of those who cultivate and use psychoactive plants – “a group of people I didn’t expect to meet” who “opened up a whole world of mind-expanding information”. (She has tried psilocybin, but “just really small micro doses because I’m chicken shit”.)

In the herbarium’s spirit collection, preserved specimens are stored in bottles “like alien creatures of horrifying nature gone wrong”, she writes. “No wonder the ghoulish among us love the herbarium so much.” It was here that she met an ophio-cordycep, also known as a zombie fungus, which – like something out of the Last of Us – attaches itself to insects and “eventually takes control of its nervous system”. The infected insect falls to the floor of the forest and burrows down; then, when the fungus is ready to reproduce, it sends the insect back up through the earth, and releases its spores as soon as it hits the air. “So it has used that bug to reproduce!” Gibson explains with relish.

“Have we colonised plants, cutting down forests, containing and constraining them?” she wonders. “Can we be so sure that the vegetable world is not more powerful? What if plants have colonised us from the start, from the beginning of time – at least western time?”

The secrets of the herbarium would also take her into the “dusty stories” of early collectors, like the intrepid German Amalie Dietrich, who travelled through remote Queensland in the 1860s collecting fauna specimens – but also collected skeletons of First Nations people, which were shipped back to Germany. The story left Gibson with “a lingering horror”.

Gibson has visited the secure freezer room where the earliest specimens reside, collected by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander in New Zealand in 1769. There are 800 specimens in the herbarium from Cook’s voyage in 1770. “They represent the landscape before we modified it,” says McPherson, somewhat diplomatically. Among them are all the Australian icons: bottlebrush, banksia, wattle, tea tree.

“There’s a lot of complexity around that the naming of plants and the associated cultural knowledge,” she explains, a discovery that led her to “face the truth about colonial erasure of Indigenous knowledge about plants. We need to tell the true story as part of decolonising ourselves and our institutions. To be honest about the past.”

For her research, Gibson talked to dozens of disparate plant people with “enormous depth and breadth of knowledge”. Botanists, horticulturalists, genetic researchers, conservators, traditional owners, historians, artists, poets. “I’m really interested in this concept called the aesthetics of care,” she says. “Living your life in a modality of caring for our environment means that you wake up with a different attitude to the world.”

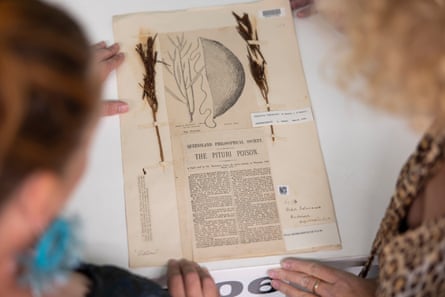

At the herbarium, McPherson opens a drawer that reveals a specimen of Pituri Deboisia Hopwoodii. She asks the Guardian not to identify where it was found. It contains nicotine alkaline, and was chewed by Indigenous Australians for its narcotic effects. “We mask the location if they contain drugs, poison or mind-altering substances because of poaching,” she says. “Their location remains secret even from most staff.” With its spiky leaves it looks a bit forlorn, like a guest who has been asked to leave a party.

Not all plants are benign, Gibson writes – “they are capable of violence too, even cruelty”. She writes about the tropical Dieffenbachia, with its toxic leaves that cause muteness, pain and difficulty breathing and were used by slave owners in the West Indies to silence slaves, and by Tucana Indians in the Amazon for poison arrows. “There’s poisonous plants everywhere,” she says.

At the herbarium we meet information botanist Peter Jobson, who investigates around 1,000 cases a year when “plants are causing problems”. Some have poisoned animals or people, for instance, or development applications that threaten rare species. He also identifies cannabis and poppies for the police. “You have got to be careful,” he says, “there is a whole bundle of things that look like cannabis but aren’t.”

Before she started work on the book, Gibson met Gordon Guymer, director of the Queensland Herbarium – a man who, like Jobson, is often asked to give evidence in court proceedings. When Alison Baden-Clay’s body was dumped under the Colo bridge, Guymer was able to identify seven types of myrtle leaf that were in her hair, and were also found in her back garden – “so she was clearly dragged through before her death”. This became crucial evidence on which her husband was convicted of her 2012 murder.

“Plants are not just an inert background to human action. They have this liveliness about them, they have this agency, this power,” Gibson says. “Everyone thinks of plants as inert and stuck in one place – until you meet the root systems and the mycelium, and you can see how plants and seeds are moved in the wind.”

Delving into the secrets at the herbarium, she discovered the capacity of plants to not just move but communicate with each other; it’s information that “you can’t unknow”, she says. If more people understood plants “as if they were kin”, she believes, conservation would be easier.

“Plants do relationships better than humans,” Gibson writes. “We could learn a lot from them … there’s so much more to them than we think.”