On 29 April 2003, 25-year-old Ammar al-Baluchi was snatched off the streets of Karachi by Pakistani authorities and handed over to the CIA.

While in CIA custody, he endured extreme forms of cruelty. He was denied sleep for days and became a human experiment for interrogators who practiced brutal methods on him to gain “official” certification in using “enhanced interrogation techniques”. Over the next three years, he was secretly shuttled between six different black sites around the world. Then, in September 2006, he was transferred to Guantánamo Bay, where he still sits in a cell. Though never convicted of a crime, he hasn’t seen a day of freedom since he was first disappeared.

According to the US government, Baluchi is one of five co-conspirators responsible for the 9/11 attacks, which killed close to 3,000 people, and he is facing charges that carry the death penalty.

Though his name and horrific experiences of torture provided the basis for a character in the 2012 film Zero Dark Thirty, no journalist has been able to talk directly to Baluchi for the last 20 years. The US government imposes strict rules on communications between him and the outside world. Journalists may not ask him questions via his lawyers, for example. But by talking to his defense team and legal experts, digging deep into the trial record, examining legions of declassified documents and partially redacted transcripts, and comparing his own written accounts of his ordeal with recently declassified CIA documents of his treatment, it is possible to assemble what might be the fullest picture yet of who Ammar al-Baluchi is, how his captors saw him, and what he has endured.

Understanding Baluchi and his torture is crucial beyond mere human interest or political curiosity. The torture he and his co-defendants endured and the long-term consequences of that abuse, including the possibility of post-torture therapy treatments, have all become part of plea negotiations, which began after the prosecution approached the defense teams in March 2022.

These talks could fail and, if they do, the 9/11 case will probably continue without any resolution for many years to come. But if the talks succeed and a plea agreement is reached, a judgment will finally be entered in one of the biggest legal cases in American history. And the United States will also be one step closer to closing the most infamous site of indefinite detention amid the “war on terror”.

But why has the prosecution even proposed a plea deal? And how likely is it to happen?

Twenty years of detention

Baluchi, who also goes by the name Ali Abdul Aziz Ali, is facing capital charges but, after 20 years of detention, the United States has yet to bring him to trial. Charges against him and his four co-defendants were filed for the second time in 2012, but since then the case has been stuck in endless pre-trial hearings.

Over a decade of hearings with no sign of a trial doesn’t seem like normal jurisprudence, but nothing is normal at Guantánamo. The case is being heard by military commission, a new and separate legal system established by the Military Commissions Act of 2006 and modified in 2009. It’s taking place in a courtroom far from the US mainland, behind soundproof glass, and on a 40-second audio delay for those – press, family and NGO observers – allowed to watch its “public” proceedings.

Most of the charges Baluchi faces in his military tribunal concern conspiracy, but conspiracy is generally not recognized by international law as a war crime and its status as such under US law remains unsettled.

The specter of torture, a crime under both international law and US statute, has haunted these proceedings from the beginning. That this torture was state policy is a dangerous fact for the US government, and from the beginning prosecutors have tried to suppress any mention of it (hence the 40-second delay) while seeking to admit statements made under torture into the record. It hasn’t been that simple.

“Administration after administration has assumed the 9/11 case is open and shut, that a jury will convict these guys, give them death sentences, and we’ll be good,” explained Lisa Hajjar, author of The War in Court: Inside the Long Fight Against Torture, a book about torture and the American judicial system in the “war on terror”. “But you cannot have anything that passes the sniff test for justice when people were tortured and disappeared for years.”

From the 2014 Senate select committee on intelligence’s “Torture Report” (which references Baluchi over 100 times) to years of litigation from lawyers, journalists, and activists, the gruesome details of torture have been emerging, sometimes in drips, other times in waves. Also emerging has been the degree of coordination between the CIA and FBI in holding and questioning men.

Prosecutors have long relied on the idea of separation between the CIA and FBI, arguing that statements made to the FBI were not coerced and are therefore admissible in court. Yet court transcripts in 2021 revealed that at least nine FBI agents were temporarily assigned as CIA agents at black sites, complicating the picture.

We can’t ask Baluchi what happened to him and, like the rest of his co-defendants, he hasn’t had the opportunity to testify about it in open court. Until December 2013, in Guantánamo’s military commissions, a defendant’s own memories of his torture were considered classified, and, to this day, any statement a defendant makes about the CIA still undergoes classification review.

But in 2021, another man, Majid Khan, openly recounted for the first time the torture he endured at the hands of the United States. This statement was part of Khan’s plea deal from years earlier. Khan, who was a courier for al-Qaida, described to a military jury the harrowing treatment he received in CIA custody. In grisly detail, he explained how he was shackled, hooded, and kept naked for days on end. He talked about being force-fed with “a plunger to force the food quickly” into his stomach and how a puree of “hummus, pasta with sauce, nuts, and raisins” was shoved up his rectum.

His eyeglasses were broken early in his confinement, and he was not given a new pair for three years, he said. He was repeatedly beaten and waterboarded. He was sexually assaulted and forcibly submerged in ice water, and much more. All this happened before he arrived at Guantánamo Bay, a place he described as “death by a thousand cuts”. During his statement, he also spoke of his remorse for his actions with al-Qaida. “There is not a day that goes by that I am not sorry for what I have done,” Khan said.

Seven of eight senior officers on his military jury were moved enough by his words to recommend clemency for the 41-year-old. “The treatment of Mr Khan in the hands of US personnel should be a source of shame for the US government,” they wrote. Khan completed his 10-year sentence at Guantánamo, which started with his guilty plea in 2012, and he has since been resettled in Belize.

While observing developments in the Khan case, the 9/11 trial prosecutors began to see more details about questionable CIA and FBI activity emerge. According to Hajjar, who follows the military commissions closely, the prosecutors soon realized that “they [could not] achieve what they had sought to achieve”. Unanimous death sentences that would withstand appeal seemed ever more unlikely, so “plea bargaining, from the government’s point of view, became necessary”, she said.

In March 2022, the government approached defense teams in the 9/11 trial for plea negotiations. While details haven’t been made public, the broad outlines have been reported. The men would plead guilty and the government, in exchange, would no longer seek the death penalty. Since Congress passed a law forbidding the transfer of any Guantánamo detainee to the US mainland, sentences would probably be served at Guantánamo Bay. The length of sentence would be worked out individually for each of the five.

Parts of the deal proposed by the defense must be decided by policymakers, so they have been labeled “policy principles”, according to court filings. What’s known about these policy principles is that they concern conditions of confinement, rehabilitation from torture, and adequate medical care. The policy principles have been sent to Caroline Krass, general counsel of the Department of Defense, who, perhaps problematically, also served as general counsel for the CIA between 2014 and 2017. And since these plea negotiations began, the military commission on the 9/11 case has been sitting in limbo, waiting for over a year for a response.

‘Enhanced measures on Ammar’

Ammar al-Baluchi is the nephew of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the man often called the “mastermind of 9/11”. (Alongside Mohammed and Baluchi, the three other men facing charges for the 9/11 attacks are Mustafa al-Hawsawi, Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Walid bin Attash.) Baluchi was born in Kuwait, but his roots are from Baluchistan, an area that covers parts of Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan, and Baluchi spent most of his teenage years in Iran and Pakistan. He then moved to Dubai, where he worked in computers before relocating to Pakistan in September 2001, after his Dubai visa expired. He speaks Arabic, Farsi, Urdu, Baluchi, and English.

The government alleges that, at his uncle’s behest, Baluchi wired over $100,000 in several transactions to some of the 9/11 hijackers. It’s said he kept the money in a laundry bag. He’s also alleged to have helped some of the hijackers in the United Arab Emirates before they traveled to the US. According to trial transcripts of government witnesses, Baluchi says he didn’t know for certain what the men he had wired money to were planning.

In April 2003, he was arrested with Walid bin Attash in Pakistan because of an “unrelated criminal lead”, according to the CIA. Reports at the time of his arrest say the men were seized with 300lb of explosives with them. First questioned by the Pakistanis (with the CIA watching a live video feed), Baluchi was described as forthcoming, even “chatty”. But the CIA wanted him, and days after his arrest he entered their custody.

Before the Pakistanis turned Baluchi over to the US, the decision had “probably” been made to use “enhanced measures on Ammar”, according to CIA documents. The US was convinced he held “perishable information” on an imminent attack on the US consulate and a residential compound in Karachi. Taken to Black Site Cobalt in Afghanistan, Baluchi immediately had his beard and head shaved and a medical professional performed the intake. Deemed healthy, he had “no apparent medical contraindications for enhanced measures”. When the US took him in mid-2003, Baluchi weighed 141lb.

By late 2003, his weight had dropped to 119lb. Initially starved of food for four days, Baluchi was given two cans of Ensure. Meanwhile, CIA headquarters sent his interrogators a list of approved techniques to be used on him: “the facial slap, the abdominal slap, walling, the stress position of standing with his forehead against the wall, the stress position of kneeling with his back inclined toward his feet, water dousing, cramped confinement, and sleep deprivation in excess of 72 hours”.

Those were the “enhanced” techniques, but other techniques, considered “standard”, didn’t need headquarters’ approval. Among them were “isolation, sleep deprivation not to exceed 72 hours, reduced caloric intake (as long as the amount is calculated to maintain the general health of the detainee), deprivation of reading material, use of loud music or white noise (at a decibel level calculated to avoid damage to the detainee’s hearing), and the use of diapers for limited periods (generally not to exceed 72 hours or during transportation where appropriate)”.

Baluchi underwent all of it, often at the same time. The lead interrogator explained that his way of using sleep deprivation was to keep Baluchi naked and standing in total darkness while blasting music by Eminem “to humiliate the detainee and make him uncomfortable in the cold”. Baluchi also described the use of music as an instrument of his torture. “I [was] suspended from the ceiling, my hands above my head. I was completely naked. It was very cold. Even that was not enough for them,” he wrote. “So they added the element of blasting music 24/7, nonstop, for months and months.”

He identified one song in particular, My Plague, by the American heavy metal band Slipknot (“Kill you, fuck you, I will never be you” is one refrain). Going through his mind “was the conviction that I was about to be killed. It was just a matter of when. I was counting every second, every minute, and on many occasions I thought I was already dead”.

He was also repeatedly doused with cold water, a procedure separate from “waterboarding”, yet still “outside the bounds of what we were supposed to be doing”, as one interrogator notes. The “water the interrogators used was excessively cold and some of it had ice in it”, a CIA report states.

Baluchi described the procedure as being pushed down on a tarpaulin, after which “one man poured ice water on my face” and “four men at the corners of the sheet would raise and lower the corners to move the ice water to different parts of my body”, eventually forcing the water on his chest “so that I would try to suck in air but breathe in water instead”. The effect was traumatizing. “I was sure they were going to finally kill me and wrap me up in the sheet,” he wrote.

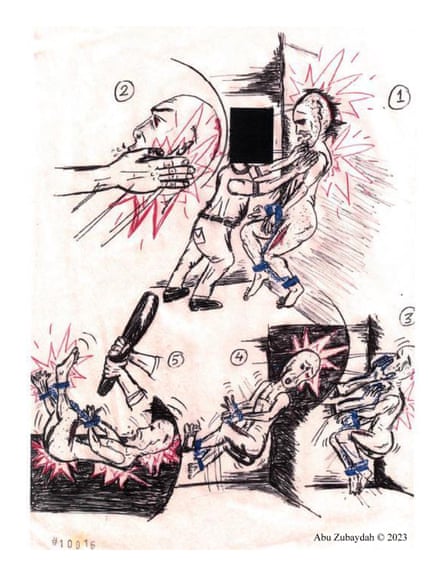

Perhaps the most shocking element of his treatment is how Baluchi became a training prop for interrogators for multiple techniques but especially for “walling”. This is when a detainee is placed in front of a wall designed to have some flexibility to it. A rolled-up towel is put around his neck, and the interrogator holds the towel and then shoves the detainee “backward into the wall, never letting go of the towel”. The technique is meant to produce a great “noise” and frighten the detainee. “The ‘goal’ was to bounce the detainee off the wall,” one interrogator notes.

To gain “certification” as interrogators, student interrogators “lined up” to “wall” Baluchi, who was kept naked during the process. The trainees would take turns “walling” Baluchi but sessions typically “did not last for more than two hours at a time”, because “fatigue would set in for the interrogator doing the walling”.

“They smashed my head against the wall repeatedly,” Baluchi wrote in court filings. “As my head was being hit each time, I would see sparks of lights in my eyes. As the intensity of these sparks were increasing as a result of repeated hitting, then all of [the] sudden I felt a strong jolt of electricity in my head. Then I couldn’t see anything. Everything went dark and I passed out.” He notes that “after this particular head injury I lost my ability to sleep ever since”.

‘He is a different person now’

The first 25 minutes of the 2012 film Zero Dark Thirty enacts a similarly gruesome interrogation of a suspect named “Ammar”, a character who shares the biographical details of Baluchi. The film-makers worked closely with the CIA on the film, and the character of Ammar “is modelled after Ammar Baluchi”, states a declassified CIA draft memorandum. In fact, the CIA provided the film-makers with the very details of Baluchi’s treatment that the government was withholding from his defense team at the time on the grounds that the details were classified.

In the film, Ammar is shown as either a brooding monster or a pathetic bag of pain. Then, after 96 hours of sleep deprivation and a clever little CIA bluff (along with a meal of “hummus, tabouli, and I don’t know what that is”, to quote his interrogator), Ammar begins talking and reliable information floods out of mouth. A CIA report, on the other hand, tells us something else about how things really happened. While he was labeled as “hard corps” [sic] and “defiant” by some interrogators, it was clear to many others that Baluchi simply told his handlers what they wanted to hear.

Interrogators expressed concern that Baluchi was “blurting out information and making it up because he wanted Agency officers to stop” water dousing him. Baluchi “was afraid to tell a lie and was afraid to tell the truth because he did not know how either would be received”, according to the CIA. He was also petrified that he would be killed once he stopped providing information. “Agency officers,” a CIA report notes, “focused more on whether Ammar was ‘compliant’ than on the quality of information he was providing.”

Baluchi’s real-life interrogators also held many opinions about his character. What emerges is a picture of a sensitive, animated, and intelligent young man. While he is twice called a hypochondriac and once histrionic, he is also labeled as “bookish”, “a philosopher, thoughtful, rational, and logical”, and “one of the more cooperative, likable, and even gentle detainees”. One interrogator who “describes her circumstances as very ‘odd’” says she found herself “sitting across from a terrorist who was responding to her as though he could be a graduate school student in the United States”.

In mid-2004 and at a different black site, Baluchi fainted in his cell. At one point, he told his captors of his difficulties reading texts. At another, he described how, after being “walled” by interrogators, “he could not recall complete memories because he tended to daydream”. By early 2006, a medical assessment noted his “attention difficulties” while concluding that “there is no evidence of any significant or prolonged mental harm”.

But later assessments tell a different story. Between 2015 and 2020, four different medical professionals, sent by his defense team, determined that Baluchi’s torture has had long-term consequences, including brain damage from the “walling”. The damage inflicted by torture has “seriously diminished” Baluchi’s “psychological functioning and has left him with mild to moderate Traumatic Brain Injury and moderate to severe anxiety, depression, and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder”, notes one neuropsychologist.

“I feel like my body and mind are deteriorating,” Baluchi wrote in 2014. “I am well educated and speak several different languages, but I can no longer read or concentrate. It is difficult for me to write letters, and at times I can’t even track a conversation. I am always exhausted, yet I can’t sleep.”

“When you sit with him and talk to him, you can see there was a person who existed before he was tortured,” Alka Pradhan, one of the lawyers on Baluchi’s defense team, told me. “He can sort of access that person. He knows that person. He has memories of that life as that person. But he is a different person now, and this is very difficult to explain to people who have not sat in a room with a torture victim.”

Calls for ‘a rapid conclusion’

In December 2021, Brig Gen John Baker, who headed the Military Commission Defense Organization for more than five years, testified before the Senate judiciary committee. “The only path to ending injustice in the military commissions – for the accused detainees, for the country, and above all for the victims of 9/11 and the other crimes currently on trial at Guantánamo – is to bring these military commissions to as rapid a conclusion as possible,” which for Baker means “a negotiated resolution of the cases”, he said.

James Connell III, the lead defense counsel for Baluchi, agrees. “Right now, the only option on the table that will bring judicial finality is some kind of negotiated resolution,” he told me, stating that the defendants in the 9/11 trial “are so damaged that they can barely participate in their court”.

Ted Olson was the solicitor general of the United States in 2001. His wife Barbara was killed on 9/11 when her plane was hijacked and flown into the Pentagon. Olson, too, believes a negotiated settlement is the best path forward. “The US must bring these legal proceedings to as rapid and just a conclusion as possible,” he wrote in the Wall Street Journal in February 2023. “True justice seems unattainable. The best the US government can do at this point is negotiate resolutions of the remaining Guantánamo cases.”

Yet, Guantánamo has remained open through four presidencies, and during that time, prisoners who have been convicted of no crimes have continued to age, their bodies and minds spiraling downward in post-torture deterioration. If opening Guantánamo was a politically brazen act in the months following 9/11, bringing the military commissions to an end would be the politically courageous one. Stakeholders from all sides of the case appear united in the view that the military commission has failed and that plea agreements must follow. All that’s needed is the political will.

But does the will exist? That’s the question looming, for more than a year, over this quiet courtroom on a remote corner of a far-away island. Meanwhile, the Biden administration continues to offer only silence on what ultimately is its decision as a presidential election approaches. This lack of political resolve means defense attorneys, prosecutors, judges, and legal advocates are all learning the very skill that the defendants and the victims’ families have honed over the last 20 years. They’re all waiting.