Ten years before he was killed on the New York subway, Jordan Neely had a stable routine.

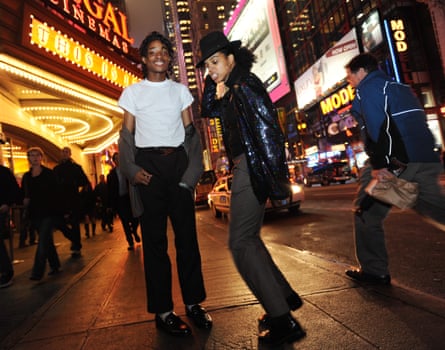

Every morning, he would walk across the Washington Bridge connecting the Bronx to Upper Manhattan. In his red Michael Jackson jacket, he was easy to see coming. When he got to the corner store near 181st Street, he’d meet Jony Espinal, a local resident who befriended Neely after recognizing him from online videos.

“He’d hang out and do a little bit of pre-dancing, to get the money to go downtown,” Espinal recalls. The two would then take the train together: Espinal to his job in lower Manhattan, and Neely to dance for subway passengers. “Everyone loved him,” Espinal says.

The young dancer would sometimes look “very downtrodden, very sweaty, and real dejected, like he’d had a rough night before”, Espinal says. But Neely “acted like everything was normal”. Espinal didn’t want to pry – Neely was “very shy” – so the two would chat about their shared love of video games and anime.

In reality, Neely was struggling to stay afloat. After his mother was murdered by his stepfather in 2007, when Neely was 14, he developed severe depression and PTSD, and also had autism and schizophrenia, according to relatives. He bounced between homes before ending up in the foster care system. In 2013, the year he started riding the train with Espinal, he also began crossing paths with police – telling them he was hearing voices.

Shortly afterwards, he became homeless, slipping into a cycle of mental health crises, arrests, and hospitalization that would continue until his death.

Neely was killed on 1 May 2023, by a subway passenger, Daniel Penny, who put him in a chokehold. According to eyewitnesses, Neely had been yelling that he was hungry and thirsty, and that he didn’t care if he went to jail. Penny will be charged with second-degree manslaughter. Jordan Neely was 30 years old.

While the manner of Neely’s killing has sparked a national controversy, less attention has been paid to how Neely slipped through the cracks of New York City’s social safety net. Jordan was reportedly on the “top 50” list, a city roster of homeless people considered to be most urgently in need of help. In a city filled with social services, how could this happen? What were the institutions that were supposed to help him – and how did his journey through the safety net end on the floor of the F train?

Many questions about Neely’s life remain unanswered, and we may never know every detail. But people who know the social services Neely encountered say they’re familiar with stories like Neely’s, and the stacked odds he would have faced in trying to find care.

As a severely mentally ill person with an arrest record, Neely would have been tossed around in a tangled web of institutions, each with limited power to change his course. Without stable housing, he would have found it nearly impossible to get the kind of consistent, holistic assistance he needed.

“Jordan Neely could have been one of a hundred other young people that I’ve worked with,” says Kerry Moles, a social worker who leads the Court Appointed Special Advocates of New York City, a non-profit that represents youth in foster care. “So it feels like a failure of the system that so many of us work so hard to improve.”

‘Just a MetroCard to survive’

One constant in Jordan Neely’s life was dancing: he began imitating Michael Jackson’s moves as early as age four. As a 20-year-old, Neely had hoped to land a job in the nightlife circuit, his friend Espinal recalls.

Neely had little stability in the rest of his life. After his mother was murdered, he moved in with his grandparents but acted out and cut school. “He will not listen to me or his grandfather,” his grandmother told authorities in 2009. In 2010, Neely threatened to kill his grandfather, and ended up sleeping in the building’s hallway, neighbors said.

In the following years, Neely became one of roughly 11,000 other children, more than half of them Black or Latino, in New York City’s foster care system. Many of the children come in with significant trauma, only to encounter further abuse or unsafe conditions in foster homes. A significant number of children in foster care end up dropping out of school, as Neely reportedly did.

“If you look at PTSD symptoms and diagnoses, you’ll see a rate in children in foster care that’s similar to combat veterans,” says Erika Palmer, a staff attorney at Advocates for Children, a New York City non-profit that helps students in foster care. “It impacts them internally. You might see a child with their head down on their desk, or with their hoodie tied up over their face. They’re physically present, but they’re not learning. And they’re left to fall through the cracks.”

People in the system are in dire need of mental health care. “If we could provide really meaningful, long term, support, supportive, non-judgmental, culturally relevant and appropriate mental health services to every child, youth and family member involved in the child welfare system, it would be totally game changing,” says Moles, of Casa-NYC. But that can be nearly impossible to get: “Any time we’re trying to refer people for mental health treatment, they’re often waitlisted, and it takes months and months.”

Larry Smith, a homeless 24-year-old who says he was close to Neely while in foster care, remembers Neely taking care of the children around him, even buying them food with his subway earnings. But Neely’s foster parents and foster care agencies ignored his mental health needs. “He was never able to get the care he needed at all,” Smith says. “He was never taken serious by anybody; nobody really cared. They felt like he had a big mouth.”

Moles says children in foster care can still thrive if they have a champion, like Casa-NYC’s court-appointed advocates. “All it really takes is one person who is in their corner and can be a cheerleader and a continuous support system for them,” she says.

Neely had no such advocate, Smith says. Neely struggled with his mental health until he was automatically discharged from foster care at 21 years old, “with just a MetroCard to survive”.

Prison-like shelters

After ageing out of foster care, Neely became homeless and began spending nights on the streets, in the subway system and New York City’s shelters.

New York City is one of the only places in the United States with a “right to shelter”: by law, authorities must provide a clean bed for the city’s homeless people – more than 70,000 by last count. But many of these facilities are notorious for crowded and unsanitary conditions where theft and assault is common.

Krys Cerisier, a homelessness organizer at Vocal-NY, a grassroots community group, compares New York City’s shelters to prisons: “A lot of folks who are released from prisons and jails often head to shelters first. And they’ll tell you, it’s the same thing,” she says. “It’s 10, 20 beds in one room, and everyone’s sort of on edge, nervous, and scared.”

In many New York City shelters, residents aren’t allowed to stay past mornings, but must return before a strict nighttime curfew or lose their bed. They can’t cook or even bring their food inside. “You don’t have autonomy over your own diet. There’s a lot of power that you lose when you are in these spaces,” Cerisier says. Often, the food that shelters offer is spoiled, unhealthy, or inedible. “These are adults eating Frosted Flakes and a loaf of bread as a daily meal,” she says.

Getting mental health care while homeless is a nightmare. While there are some shelters set aside for people with serious mental health needs, 26% of homeless shelter clients with serious mental illness were not placed there, a city comptroller’s report found in 2022. Mental health shelters “aren’t actually equipped to deal with extreme levels of mental illness”, says Cerisier, “So it’s often easier for them to take people who don’t really need it, because they just need less resources.” And when people do end up having serious mental health crises inside shelters, staff often call the police – “so folks get arrested and dragged out”.

Advocates say a preferable alternative is “safe haven” shelters, with low entry barriers, no curfew and some on-site psychiatric resources. But the city’s roughly 1,400 safe haven beds aren’t nearly enough. (The mayor’s office says it’s planning to add a few hundred more by the end of the year).

An even better option is supportive housing: a more permanent kind of group living, with private rooms, shared bathrooms and kitchens, and social services on premises – a setup that can help halt someone’s downward spiral, says Matt Kudish, the head of the National Alliance on Mental Illness of New York City (Nami-NYC).

“If there is a mental illness highway, and at the end of that highway is jail or prison, we need as many off-ramps from that highway as possible, so that people who are living with mental illness have opportunities to get help instead of handcuffs,” he says.

But New York City law requires people to stay in a shelter for 90 days before they can apply for supportive housing, and even then, vacancies for units are scant. Recent data shows just 16% of New Yorkers who are approved for supportive housing actually get placed in a unit.

There are a few units set aside for young people exiting the foster care system, but demand far outstrips supply. Cerisier says even supportive housing landlords often avoid leasing to people with extreme mental health needs.

The more common result, she says, is that “the people who actually need help end up on the train or on the streets”.

A patchwork of care

As Jordan Neely rode the trains around New York City, he crossed paths with another layer of the city’s social safety net: homeless mobile teams.

There are the city’s mobile crisis teams (MCT), run by hospitals or non-profits, which are designed to rapidly respond to someone having a mental health crisis, and hospitalize them if necessary.

Separately, there are mobile treatment teams, which provide continuous care to assigned homeless people with mental illness. In agency lingo, they’re called assertive community treatment (ACT) teams, or intensive mobile treatment (IMT) teams for particularly tough cases. These consist of social workers, psychiatrists, and peer specialists – referring to trained advocates who have experienced similar hardships as their clients. The waitlists to get treatment from these teams are hundreds of people long.

Beth Diesch, the director of homeless mobile teams for Community Access, a New York City non-profit, runs six of these teams: one ACT team and five IMT teams. Diesch says success requires building trust with clients, and that starts with respecting their autonomy: “If somebody is not in agreement with what a third-party says their mental health treatment is going to be, they’re very unlikely to continue following it independently. If a doctor says ‘take this pill’ and you don’t think you need it, you’re not going to do it.”

If clients refuse treatment, Diesch tries to avoid calling the police. “If it falls on NYPD, it’s going to involve handcuffs, and people are often forcibly handcuffed to a bed in the ER setting. And there’s often a cocktail of Haldol and Ativan that can be forcibly administered to sedate somebody. It’s going to be traumatic, and at the end of the day, it’s largely ineffectual,” she says.

If clients are threatening themselves or others, she offers to accompany them to the hospital: “We never want to just sic the dogs on anybody and bump them off somewhere with no support.”

But the teams can struggle to keep track of their clients. “There’s so many different programs and so many different teams in the city that have access to pieces of the information” about a homeless person, says Diesch. “Often there’s duplication of outreach happening.” If a client ends up arrested or hospitalized, often the team won’t learn of it until days afterward.

Another issue is a lack of resources. The city sets the pay rates for IMT teams, and workers are underpaid, causing high turnover and burnout, says Cal Hedigan, Community Access’s CEO.

And ACT teams are funded by insurance reimbursements, which means the teams don’t get paid when treating homeless clients without coverage.

The final layer

Without stable housing or consistent mental health care, Jordan Neely quickly hit the system’s bottom layer.

Under longstanding New York City laws, police may forcibly hospitalize someone displaying threatening behavior, but last November Mayor Eric Adams issued a controversial directive empowering city workers to involuntarily hospitalize people with mental illness even if they pose no harm.

Over the last decade, police reportedly arrested Neely 42 times for infractions such as drug use and fare beating, and responded to another 43 calls for an “aided case”, meaning someone reported that Neely was sick, injured, or mentally ill.

Notes from police and mobile crisis teams show his condition deteriorating over that span: In 2016, officers brought him to a hospital when he said he was suicidal, then again when he was threatening others on the street. By 2018, police were dragging him to the hospital every few weeks, even when he refused to go. By 2020, he had lost weight, was disheveled and said he’d been off his medication.

In 2021, Neely was arrested after punching a 67-year-old woman in the head, severely injuring her and landing him in Rikers Island, New York City’s notorious jail, on charges of second-degree assault. A judge released him in February, as part of a plea deal requiring him to stay at an intensive inpatient treatment center for 15 months.

But he walked out after 13 days and disappeared. Less than three months later, Jordan Neely was dead.

‘Jordan needed someone on Jordan’s side’

Could things have turned out differently? After Neely’s death, Adams initially appeared to side with the killer: “I was a former transit police officer and I responded to many jobs where you had a passenger assist someone,” he said last week. He changed his tone in a speech on Wednesday, calling the dancer’s death a “tragedy that never should have happened”.

“There were many people who did care about a man named Jordan, but it wasn’t enough this time, and we must keep trying before we lose another Jordan,” Adams said.

Adams also used the moment to reaffirm his involuntary hospitalization directive, something that he called to be passed as a state law. “People in crisis often need extended hospital care to fully recover.”

That’s a mistake, says Charles Sanky, a New York City emergency physician, who says the city often treats the emergency department as a “stop gap, end-all-be-all, where if we have nowhere else, that’s where people go”. In reality, the ER tends to be overcrowded and under-resourced, without the “space or all the tools to actually intervene in a meaningful way”, he says. “And what ends up happening is that people get sent back out and they slip through the cracks.”

Kudish, the Nami-NYC head, believes what Neely really needed was someone consistently in his corner: “One person who’s following Jordan. Not Jordan in the context of this hospital, then Jordan in the context of jail, Jordan in the context of mobile crisis treatment on the street, or Jordan in the context of a shelter … It’s not to say that the people who were working in these different siloed systems didn’t care about him, but at some point, their role ends,” he says. “Jordan needed someone on Jordan’s side.”

The best way to achieve that? Housing. “Give people a safe place to lay their head, and supportive housing with wraparound services,” Kudish says. “If you start to meet those basic needs, then maybe – and there’s no one easy answer to this stuff – but maybe all the rest would have started to fall in place over time.”

Near the end of Jordan Neely’s life, there was one last layer of New Yorkers who were trying to catch him: his fans.

Nine months before Neely died, one concerned fan started a Facebook group to look for him: “We want to support and help him, where ever he might be,” wrote the admin. “Fans are worried he could be homeless somewhere in NYC … let’s try to find Mr Neely.”

Last week, after Neely’s death, the group turned into a memorial. “You saw a lot of trauma in your life. You tried your best to use your talents to make others happy … when you were in crisis you deserved compassion,” one user wrote. “Instead others decided that you were a threat and silenced you forever. We will remember your name.”