In his first weeks in Australia on a student visa, Om Dhungel wanted to get a job to send money to his family in Nepal, all refugees driven out of Bhutan. But people here struggled to understand his accent. Sometimes, they would mistakenly call him Tom.

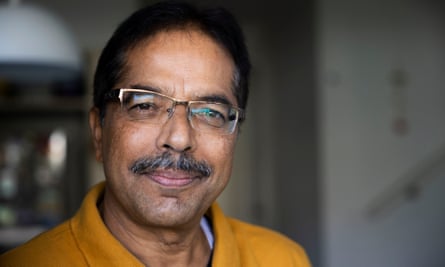

Soon after arriving in Sydney, he spotted a vacancy sign on the street, and excitedly pulled his borrowed car in to apply for a position – but it was a motel sign, not a workplace. “I laugh at it now, but I actually cried after that,” chuckles the slim, moustachioed and bespectacled 61-year-old, almost 25 years later.

The former senior telecommunications engineer is seated in the front room of his home in Blacktown, 34km west of Sydney. His arrival in Sydney came via escape from persecution in Bhutan and years living in poverty as a refugee in Nepal, experiences he writes about in Bhutan to Blacktown: Losing Everything and Finding Australia. The book is a memoir and provocation about rethinking how we deal with refugees, co-authored by journalist James Button.

But, he says, he realised early in his Australian life that recounting his own traumatic stories was “nurturing my wound, my victimhood”.

Dhungel has become a cultural leader to many who have followed his path to this area, one of Australia’s most deeply multicultural communities, where residents are drawn from 188 countries. Walking with Guardian Australia through the neighbourhood where he lives with his wife, Saroja, a microbiologist at a nearby hospital, he argues it is misguided to see refugees as “vulnerable” and “victims”, ideas that he says have shaped Australian refugee settlement policy – to its detriment.

He encourages new arrivals to volunteer in community activities to get experience that will help them find work, and when seeking local qualifications to “study something that they love but that is in demand”. Volunteering could teach people local norms, guard against loneliness and help refugees and migrants “not just settle, but become part of Australia”.

His is a view which sees new arrivals as people with something to contribute. “No one wants to paint refugees as passive recipients of services, as victims,” he writes. “But such attitudes have become baked into the funding model.”

A narrow focus on widespread vulnerability underestimates refugee strength and potential, says Dhungel. Yet refugees, especially the women in his life, have been fierce and strong.

A year and a half ago, his father, Durga, a farmer and shopkeeper from the tiny southern Bhutanese village of Lamidara, died aged 94 among his wider family here in western Sydney. It was a “good life and a good death”, says his son, even though some 30 years earlier soldiers had three times arrested Durga at the family home he and his wife, Damanta, built. The soldiers beat the father of 14 until he collapsed, the torture leaving Durga with scars and a rigid back for life.

The family were among 100,000 targeted by the Bhutanese king and his ministers because of their Nepali ancestry. Their property and home – “they had carried the stones, planted the orchard” – was given away to others.

His mother Damanta was a fierce force for the family. “When my dad was going through the pain and mental suffering, the loss of the dream he had back home, my mum was pulling us all together with her mental strength,” he says. “The day-to-day living happened because of Mum.”

Dhungel chats with local mothers and babies at a cafe here in their idyllic residential lakeside development known as Fairwater. His daughter, Smriti, has a house a couple of blocks back from here with her husband.

Damanta lives five minutes away; the spritely 93-year-old embarks on daily walksand yoga. While Damanta’s children today are scattered across the United States, Nepal and Bhutan, some of the family has resettled near her. With its uniform lines of trees on nature strips, ducks upon the water and its own underground renewable geothermal energy supply, the western Sydney suburb is vastly different from their Bhutanese village that lacked phones, electricity and even a road.

By staying close, generations of former refugees bolster one another.

Today, Dhungel values above all else community, family, and human connection. These values were forged witnessing the struggle of life in refugee camps, where informal schools under trees promoted a “culture of learning” that drove change in “fixed ideas” such as the role of women. Living in Nepal, he advocated for the world to take notice.

“We all are vulnerable, but at the same time once you go through that [refugee] experience, to categorise you as ‘weak’ and ‘vulnerable’, I don’t think is a fair way to move forward,” he says.

Australia, he argues, must recognise refugees as resourceful and strong – because they are. “How do you tap into the strength of these people?

after newsletter promotion

“If [for instance] a single mother comes to a settlement country, I love to hear about, ‘hey, how did you manage that?’, and learn from that, and then use that experience to lift her to where she can then become an inspiration, rather than saying ‘you are a victim’ or ‘poor you, you’ve gone through this’, which is done with the best of intentions, but will make her weaker.”

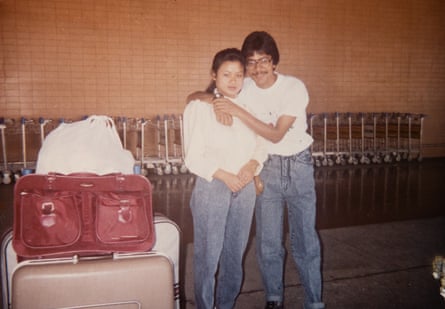

Dhungel himself became such a source of inspiration, first setting up a local Amnesty chapter to draw attention to the Bhutanese government’s violence. In 2007, he and Saroja were among four couples who formed the Association of Bhutanese in Australia which began helping to settle Bhutanese migrants in Australia and has since been referred to as one of the most successful refugee settlement projects in Australia.

The ethos imparted was that these immigrants would not become dependent on the formal service sector but stand on their own, with grassroots community support. Australia is “fortunate” to have a “good, strong service sector”, Dhungel argues, but service providers need to better include communities in the settlement process, with many spending too much money on some tasks communities could do themselves.

While most refugees have trauma that needs addressing, their needs are wider. Dhungel speaks of how beneficial it has been to all generations to have grandparents beyond working age settle with their families.

Does that mean Australia should have a greater emphasis on keeping refugee families together for the sake of communal culture? “That’s where we need to rethink, have a good debate,” he says.

The balance is fraught: community is central to people settling in Australia, but the “paradox” of human interdependence is “we must solve our own problems, set our own course, yet we are nothing without other people”.

Dhungel writes he has “learned that we must resist the powerful forces in contemporary society that seek to define us on the basis of our ethnic or cultural identities rather than as Australians, as human beings, as the residents of a suburb or a street”.

He says: “If we empower communities or individuals with a narrow identity, when crisis time comes then it can easily be destructive to the other communities.”

Dhungel long ago felt the hard blow of such division in a country that sought to divide according to genealogy. But isn’t there the risk of homogenising the wonderful diversity of Australia when religious and cultural identities become secondary?

“That’s so true, and it’s an evolving thing,” he says. We drive past Fairwater’s houses built around a lake and a park with its ornamental pear trees as he drops me back at Blacktown railway station a few minutes away.

Dhungel points out the Fairwater residents’ committee’s “community model”, initially established by the suburb’s developer, which states that “we are Fairwater residents first”. On the committee are people who happen to live side by side, be they Hindu, Muslim, Christian or Buddhist.

“We need to have that commonality,” he says, “and then the other ingredients, diversity, should come on top of it and add to the richness – not the other way around”.

-

Bhutan to Blacktown: Losing Everything and Finding Australia is published by NewSouth.