Stock images are everywhere, and you probably rarely notice them: on billboards and websites, plastered across adverts, groceries and print media. Shooting original photography takes time and money. Stock-image banks – which contain existing images that can be licensed for use in a flash – make for a cheap, easy alternative. When stock-image libraries first opened in the 1930s, customers, often magazines, would have to wait 24 hours for a physical image to be found in an archive and delivered. The internet catapulted this demand sky‑ high. Websites need a constant stream of content. Memes are an unregulated stock-photo market of their own.

Now, stock-photo websites collate millions of images, with almost any picture you can imagine available instantly. Urgently need a lonely Santa, a flying baby or a man dressed in a suit sitting in a bath with a rubber duck on his head? A couple of clicks and it’s yours.

By design, the models who populate stock photos are anonymous; figures on to whom all manner of messages and meaning can be projected. Here, six people – from professional posers to those who were shocked to discover they had become stock-photo models – explain how their pictures ended up in the archives.

‘I studied the blurry picture: surely it couldn’t be me?’

Shubnum Khan

I was a fresh-faced 24-year-old master’s student at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa, when I heard about a photographer who was offering students free portraits. A friend heard it was for his art project. I thought he was expanding his portfolio. Either way, it meant free pictures. What was there to lose?

We went along, were welcomed and asked to sign a form. It felt pretty standard. I assumed I was giving him permission to use the pictures for his own purposes, so happily scrawled down my name. We’d been told to come in normal clothes; no makeup. One by one, attendees were called into the studio. When it was my turn, it was quick and straightforward: I was asked to do three simple expressions – happy, straight and “crazy” – then was on my way. A few weeks later I received my portraits via email. They weren’t exactly flattering. I closed my inbox and carried on with my day.

Two years later, in 2012, I was teaching at the same university when, out of the blue, a friend messaged telling me to check my Facebook. An acquaintance had posted a photo on my wall, asking: “Is this you?” Alongside it was a picture of a newspaper advert promoting immigration to Canada. I studied the blurry picture: surely it couldn’t be. When I looked closer, there was no doubt – it was me.

I panicked. How could this have happened? It was a well-respected publication. They wouldn’t have stolen my image. Then another friend commented: “Wait, doesn’t this look like the picture from that student photoshoot?” She tagged the photographer, who responded, in essence saying: “What’s the big deal? You signed a release form, I’ve been selling those pictures as stock photos.”

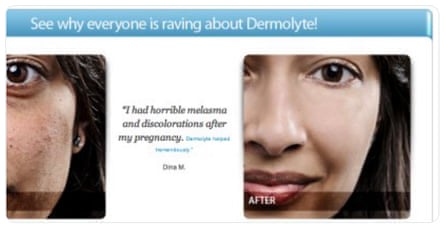

Shocked, I reverse-image searched the picture on Google, and was stunned. There I was, in all corners of the web and all around the world. I was the face of eye cream, skin-lightening, makeup, laser treatments, dentistry. I was in ads for banking, insurance, teaching and management. There were magazine covers; a textbook; a Moroccan dating website. I sold carpets in New York, travel packages in Cambodia and, yes, promoted immigration in Uruguay and Canada.

My name, nationality and race were altered at whim. I was Bonney Seng; Phoebe Lopez; Chandra; Kelsie from Florida. In an Instagram advert for skin-lightening pills, my skin has been Photoshopped from dark to fair. Until then, I had absolutely no idea any of this was happening.

I didn’t know how to feel. Should I be scared, alarmed, outraged, or find it funny? It made no sense. I contacted the photographer and asked him to remove my images. Initially he resisted, arguing that I’d signed away all the rights. I kept up the pressure and finally he agreed, adding, however, that rights already sold could not be rescinded. In short, my images could for ever be in use.

Over the following years, my face would be used occasionally. A few months ago, I was plastered across highways in India. When I looked online, I found other women of colour who had been treated the same. I decided to write about it in my last book – to encourage other people to be conscious of what their pictures might be used for and read the paperwork first. And to take control of my story.

I still don’t know how widely the images have been used – the photographer doesn’t keep a record of individual sales – but I know it’s extensive, and I’m not sure whether to laugh or cry. It’s still unbelievable to me, but because I’ve never seen a physical ad in person, I can almost pretend it’s not real.

Shubnum Khan’s novel The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years will be published by Oneworld in February 2024.

‘I was shocked to discover I had become the face of generic white men’’

Reed Kavner

The comedy community in New York has been the centre of my social life since I moved here in 2015. Many of my friends are building careers for themselves as standups, writers, actors or producers. Nobody too famous, but I’ll occasionally see a buddy in a yoghurt commercial.

A few friends write for Reductress, the humour website that parodies the style of women’s magazines (“How to love your boyfriend even if he’s not Mark Ruffalo”). It pairs its articles with images, often pulled from its own collection. Over the years, more and more friends modelled for Reductress’s photos, and I found myself getting jealous. I wanted in on the fun.

Then, in 2018, I got a text from a friend who writes for the site, asking if I’d be in a photoshoot. I’ve never responded to a text so quickly. A week later, I was on my way to Reductress’s Manhattan office with a fresh haircut. It was an informal setup. One of the site’s founders wielded a cheap digital camera and led me and the dozen or so other volunteer models from location to location. I sat on the stoop of an apartment building; stared straight down the camera; poured coffee in the office kitchen.

I waited eagerly for my face to appear on an article. As a feminist satire site, it often writes about fictional men being awful, so I knew what to expect. Would I be a shitty boyfriend? A condescending colleague? Hopefully both. I couldn’t wait to find out.

Finally, a few months later, I saw my photo. I was the face of a man who had supposedly written a comment piece titled: “Most guys just want sex, but I would be OK with hand stuff.” Perfect. I was thrilled, and still have a screenshot of that article on my dating profile today. Every few months, I’d see another. It never got old. There was: “White guy excited to burn down the system and also control the rebuilding effort”; “Man stops touching women he doesn’t know because of coronavirus, yep, just coronavirus.” Soon, I started to see myself less often. Perhaps the website replenished its bank of pictures. Or perhaps a new editor thought I was too good-looking to portray gross creeps.

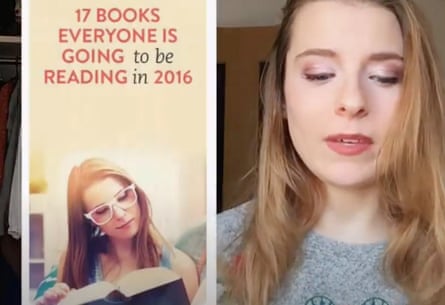

In the summer of 2021, more than a year since I had last seen my photo in Reductress, I received a notification from a follower on TikTok. They tagged me in the comments for a video, so I watched it.

In the clip, a young guy was acting out a story of a time he hit on a woman, only to be interrupted by her white boyfriend. The clip ends with a full-screen photo that is supposed to represent the boyfriend. It was a photo of me. I was perplexed. Of course, I knew these pictures were online, but there are endless photos available. How did he choose me?

When I asked that on Twitter, someone pointed out the obvious. He didn’t choose a picture of me specifically. He chose a picture of a generic white guy. On a hunch, I Google image-searched “white guy” and there I was, with deadpan face and striped blue T-shirt.

Once I figured out what was happening, I made my own TikTok video. I explained how I was shocked to discover I had become the face of generic white men, and how bizarre it was to have strangers on the internet commenting on my appearance. That video quickly gained millions of views, inspiring more people to find my photo by searching for “white guy”, driving my picture to the top of the results. I saw it being used as people’s profile photos on TikTok and LinkedIn. Someone said they’d seen my face on a dating app. Another person got in touch to say they’d used my picture in a school project. I hope they got a good grade.

For many people, Google image search is their stock-photo library. If it’s on Google, it’s ending up somewhere. There are so many contexts in which someone might search for and grab an image of a “white guy”. In some, I imagine I’d be fine with how they’re using my face. But I’m sure there are others where I’d be far less pleased.

If you’d asked me whether I wanted my face to appear whenever someone was looking for a “white guy”, I’d have politely declined. Still, it’s a good story to tell on stage – and provides more exposure than a yoghurt commercial.

‘A mate in Australia left me a voice note: I think I just saw you on the side of a bus’

Niccolò Massariello

In 2016, I had just been through a breakup and was feeling self-conscious. I had this friend, a photographer, who took pictures for a stock-images website. I asked: can you take some pictures that make me look good? I had no photos to use for online dating, and I needed a bit of an ego boost.

The shoot itself was fun. We did all sorts: I wore a suit, played with his dog, got angry at an iPad. It turned out I’m fairly good at making weird faces on cue. I signed some paperwork to allow my friend to use the images. A few days later, he sent me a few straight ones to use on my CV. I hadn’t thought much about what might happen after. I had no reason to think anyone would be interested in pictures of my face.

Less than a week later, my friend told me that someone had already used the image. It was on a strange website about men being the superior sex. It was weird, but I assumed it was a one-off incident. And it was a pretty niche website: who would ever know?

However, over the following months my face kept appearing in more and more places. I hadn’t realised just how widely stock images are used. I was flogging gluten-free options for a horchata brand, and encouraging people to drink Colombian liquor. I was in Germany, Saudi Arabia and the Netherlands. I was the lead picture on all sorts of online articles: “How to mindfully deal with jerks” (I was the jerk); “The vindictive ex: when hate comes before children”; and one on catcallers.

Then a girl I knew in Colombia WhatsApped me a page from a national newspaper. It turns out I’d recently become the face of paraphimosis – a highly unpleasant and painful-sounding medical issue with the penis. For good measure, the newspaper tweeted it as well. Then a mate in Australia left me a voice note: “I think I just saw you on the side of a bus.”

Friends asked if I was worried or scared, but I wasn’t. The only thing I wondered was whether I could get paid. Turns out that wasn’t the case. If anything, I became addicted to people telling me they’d spotted me: on huge screens at conferences, plastered over metro stations, or on an in-flight brochure encouraging people not to get drunk. Two years later, when my image started to pop up less regularly, I even organised a fresh photoshoot with the same friend in the hope that my new pictures would take off in the same way. They were a total flop.

‘Over the years I’ve been Santa’s wife, a chef, a vet, a hotel maid, milkmaid, butcher, baker’

Adriana Rodriguez

I’m a stock-image model by profession. I’ve been doing it for the past 11 years. But starting was an accident. In 2005, my brother – a graphic designer – was designing websites in London. It was during the early years of stock images being used online. He realised there might be an untapped market and uploaded some images to a stock-photo platform. One time he was back home in Colombia for a few months and asked if some friends and I could model in his shoots.

The setup was fairly basic: a white sheet hanging from a curtain rail acted as a backdrop in our living-room studio. We made it up as we went along: random poses and strange scenarios. Over the years, I’ve been Santa’s wife, a chef, a vet, a hotel maid. I’ve milked cows, worked at a (bloody) butcher’s shop and been a baker.

The images did well. We decided to see how far it could go. He invested in lights and equipment; I learned how to do makeup properly. We focused on education, medical and business imagery at first: the stats suggested they would sell. I would sit behind a desk, dress as a doctor or stand by a whiteboard; we would re-enact everything and anything we imagined might happen in these worlds.

When we started, there wasn’t much diversity: most stock models were European and American, with lots of blond Caucasians. We were something fresh. Soon my face was everywhere: Australia, Israel, Jordan, on TV shows and on a fake advert in a Netflix drama. A picture of me dressed as a stewardess was used in a comedy segment on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah.

Measuring the scale is impossible. There must be at least 5,000 pictures of me in our database. We don’t get told who purchases our images, or how they’re used. But I get sent at least three messages a week from people flagging where they’ve seen me. I’ve started a “highlights” section on my Instagram to keep tabs on it: I’m in Miami shopping malls, on Spanish ATMs and on giant Portuguese roadside billboards. I sell credit cards in Mexico, air travel in Brazil and glasses in Greece.

Occasionally, the pictures have been used in a way I find uncomfortable – say, for diet pills. But there’s nothing I can do about it, and people who know me realise it’s not a reflection of who I am. I’m a professional model and have made a career from it. Actors don’t worry about playing different characters in movies.

One of the main stipulations is that my pictures can’t be used for political purposes or for anything related to pornography. Here in Colombia my face was used by a political party I don’t agree with and we made sure those images were taken down – we own them, so we can assert some control.

Today, my brother works from the UK and comes to Colombia for shoots when necessary. I model and handle the back-office work. I also keep an eye on trends and what’s happening in the news. When virtual reality started being talked about, we did a shoot with headsets; when ride-sharing apps became popular, we needed pictures of people ordering their cars. We respond to what’s needed and get the images online as quickly as we can.

‘My face became one of the most widely used memes in the world’

Kyle Craven

Through high school, I was always the class clown; a comedian. I took very little seriously and was far more interested in pranks and jokes. I went to a Catholic school – they were very strict about the clothes we wore. That’s why I always looked forward to yearbook photo day: it was a chance to see what trouble I could cause.

When that day came round in my junior [third] year in 2007, I’d purchased a tartan sweater vest. I asked for a purple background; everyone else chose simple blacks and greys. I rubbed my eyes to make them all puffy, and when my photograph was taken I did this gawky grin. I thought the result was a masterpiece. It got a big laugh when the picture was handed out in class. The school principal, however, was less impressed. They insisted I retake my picture. With the original destined to never be published, I uploaded it to Facebook.

Fast forward to 2012 and I was in my final year of college at Kent State University, Ohio. Ian Davies, my best friend from high school, was living in LA. We were both really into Reddit and one morning I woke up to a voicemail from Ian: “No big deal, have made you internet famous, check the link.” The night before he’d been messing around on the Advice Animals Reddit page – one of the earliest spaces on the internet for viral memes. Posters would upload a simple image of a person or animal in the hope of turning them into a meme. It’s how some of the biggest memes in internet history were created.

Ian wanted a piece of the action, too. He had pulled my dumb picture from Facebook and posted it to Reddit. He needed to name it, but Bad Luck Kyle didn’t quite have a ring to it. He thought some alliteration might be more catchy. And, with that, Bad Luck Brian was born.

It took a couple of months for the momentum to pick up, but then it was all over Reddit. It happened organically, I’m still not totally sure how. Meme culture was in its infancy. I found it very funny, but assumed it would last a week or two, then die off. Instead, it got bigger and bigger. My face became one of the most widely used memes around the world.

When brands asked to license the image, I spotted an opportunity. I had no issue with people using my picture for their own purposes for free, but if companies wanted to profit from it, why not make some cash? I did a McDonald’s campaign to promote a new competition they were running (with 1-4 odds of winning, even Bad Luck Brian can win).

We licensed the original image for T-shirts in Walmart and to be used in Volkswagen’s 2014 Super Bowl advert. My image has been used in more than 35 board and card games. I’ve been invited to make appearances all over the world; my face is in a museum in Berne, Switzerland. It’s a stock image, really. The photo is free to internet users, and to corporations at cost. Now it’s a side project that gives me all sorts of opportunities – something different from my nine to five in our family construction business.

People get in touch to say something similar has happened to them. I always give the same advice: you just have to embrace it. There’s nothing else you can do. Publicly resist and the trolls will find a way to keep on pushing it. Once you’re going viral, you’ve been placed in the passenger seat. And the internet is going to take you on a ride.

‘My face is a blank canvas. People do with it whatever they please’

Andi Dean

When I was an 18-year-old student in North Carolina, I did a few shoots for free with photographers hoping to build their portfolios. I wanted to see if modelling could be a hobby, or even a side hustle to help me pay my way through college. Then a woman messaged me to ask if I’d be interested in a paid stock-photography gig.

She lived about 45 minutes away, in the middle of the forest. I packed various outfits and drove out to meet her, slightly nervous about heading alone to a stranger’s house. Thankfully it was all legit – she took me into her garage studio and we got to it. I spent a lot of that day jumping in the air while wearing long dresses. We did holiday-themed shoots. I put on Christmas jumpers and unwrapped presents, then quickly switched to Valentine’s Day, with red clothes and boxes of chocolate. For a few hours’ work, I earned a couple of hundred bucks. That felt like a lot to my student self.

I can’t quite remember when I first heard my picture was being used. Slowly but surely, people would get in touch out of the blue and tell me where they’d seen it. I started a list of all the locations: a Mexican-English language school running a campaign for online classes. A billboard in Liechtenstein. China Airlines. Facial hair removal in Tokyo. An endless stream of social media ads.

For the next five years, I did a shoot with the same woman annually. I stopped only because I relocated to Japan. Now I work in marketing, I understand the value of stock photos. I like that I’m helping others to make that conversion or sale. Stock images are integral to so many industries, mine included. You probably don’t even know how many you’re exposed to: on Reddit, social media, YouTube, apps, in newspapers. You name it.

Yes, my face is almost famous – it has been seen by millions. Yet I’m also entirely anonymous: nearly everyone who uses or consumes my image projects whatever they wish on to it. My face is a blank canvas. People do with it whatever they please. But, for me, every shoot has a special spot in my mind – each captured a moment in my early adulthood. Living so far away from North Carolina now, I enjoy seeing those photos and being reminded of my life back home.