Ross Knight – bass player, singer and mainstay of Australian punk heroes the Cosmic Psychos – tells a good yarn that deftly illustrates his group’s public image.

The Psychos – who are celebrating 40 years since their humble beginnings in central Victoria, as a school band originally named Rancid Spam – were unlikely guests of honour at the Australian embassy in Berlin in 2013, commemorating 60 years of friendship between Australia and Germany. The band had driven all night from Utrecht in the Netherlands, arriving in Berlin about 3am. Of course they found a bar before rolling up to the embassy a few hours later, very much the worse for wear.

As they slid open their van’s side door, beer cans spilled out, rolling towards the assembled dignitaries like unexploded mortar shells. The band followed the cans into the light, blinking, Knight dressed in Blundstones, jeans and a Yakka shirt and their guitarist, John “Mad Macka” McKeering, in a tracksuit.

“We were standing next to generals and majors and ambassadors and goodness knows who else, going, ‘Bloody hell, how did this happen?’” Knight says, chuckling.

The Cosmic Psychos are an Australian institution. Sounding like the Ramones fronted by the Crocodile Hunter, they write songs in a distinctly Australian vernacular about drinking, fighting, roadkill and punching above your weight.

They’re the self-described Blokes You Can Trust – title of their third album and the band-sanctioned, fan-funded documentary from 2013.

Treading Spinal Tap’s famous fine line between stupid and clever better than anyone, the Psychos’ bludgeoning take on punk has proven durable, influencing everyone from L7 (who covered the band’s Lost Cause, rewritten as Fuel My Fire, later recorded by the Prodigy) to Amyl and the Sniffers.

Telling the cartoon version of their story is easy. The band’s humanity is deeper, more complicated and more intelligent.

Knight, now 62, is the constant. Dean Muller replaced the original drummer, Bill Walsh, in 2005 after a bitter falling-out with Knight. McKeering, who had cut his teeth in a like-minded Brisbane trio called the Onyas, came onboard a year later after the death of Robbie “Rocket” Watts. (Watts replaced the original guitarist, Peter “Dirty” Jones, in 1990.)

Eamon Sandwith, the singer and bass player of the Chats, is a fan; having supported the Psychos in their early days. And the Chats have just finished a tour headlining over their heroes in the US. “They’ve taught me a lot about not caring what people say about you, how to conduct myself in a somewhat professional setting, and plenty about dealing with hangovers,” Sandwith says.

One on one, though, the Cosmic Psychos give more fucks than they might let on. “Anyone who knows the Psychos personally will tell you that they are some of the funniest, kindest, most generous people in this industry,” Sandwith says. “No egos whatsoever. I feel honoured to call them my friends.”

The documentary about the band provided a glimpse into Knight’s life outside his hobby band. For our interview, he’s calling from the top of a hill on Spring Plains, the farm on which he grew up and still lives. “I can’t imagine being anywhere else,” he says. “I owe more money than the American government but I don’t really care.”

Knight is no ordinary rock star. He has weightlifting world championship belts in his age and weight division, and the body to show for it: “I’ve got two new hips – I’ve got to get another hip done again, it didn’t work too good,” he says. “And me back’s fucked. But apart from that I’m in reasonable nick.”

It hasn’t stopped him lifting. “I do it for the black dog, actually. If I don’t lift weights, I can just feel the world close in a bit.”

The documentary also touched on Knight’s relationship with his profoundly disabled son Jika, who died this year aged 26. As his carer, Knight spent a lot of time lifting Jika. His loss represents a different kind of weight. “Grief, you just carry it on your chest, and then you put it on your back, that’s what I’ve been told,” he says. “It’ll never leave.”

McKeering, who is based in Brisbane, says the band was united in grief. “We were all just fucken smashed when it happened, because we thought he was going to go on forever,” he says. “We knew about a week before it happened that it was a chance, and we thought, ‘Oh no, he’ll get over it, it’ll work out,’ and it didn’t.”

after newsletter promotion

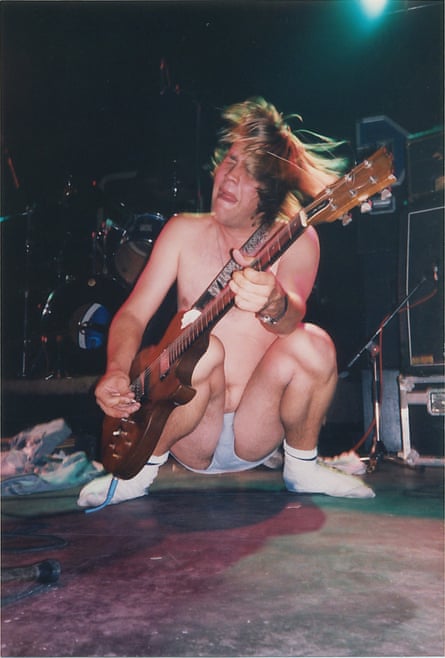

Like Knight, there is more to “Macka” than meets the eye. With the hangdog features of an oversized bloodhound and a mouth like your old uncle at a wedding, the author of the anthemic Fuckwit City usually takes the stage barefoot, in shorts and singlet. Later he’ll strip to his waist, rolling his substantial beer gut for the crowd.

McKeering is also a polymath: a lawyer with a degree in political science and a master of arts in musicology; and a former competitive swimming coach who, as a junior, raced (and beat) Kieren Perkins. “It was boring,” he says, grinning, when asked why he gave up swimming. “Playing guitar was more fun.”

In 1999 he was diagnosed with schizophrenia, a condition about which he is open. “I had it, but I beat it,” he says. How did he beat it? “Taking pills and getting my life organised.” What happens i he doesn’t take the medication? “I go into a mess again.”

The Psychos aren’t stopping anytime soon, though Knight says he’s just about done with overseas touring. “I’m quite happy just dagging about Australia and doing, I dunno, half-a-dozen to a dozen shows a year, if we feel like it,” he says.

“I still enjoy getting in me shed, having a few beers with the dog and playing bass. I can’t imagine ever not doing that. As long as I’m up there writing” – he corrects himself – “re-writing the same song for 40 years, with the same three chords, we might as well get out there and have free beer every now and again, and I can’t see why I’d not want to get free beer.”

I ask Knight his favourite drinking song by another artist. “Oh, I suppose Somebody Put Something in My Drink by the Ramones,” he says. “Hank Williams wrote some terribly sad drinking songs. I don’t want to glorify myself being a functioning alcoholic, but … ”

“Oh, come on Ross,” I interject. “Your last album was called Mountain of Piss!”

“Yes, I know, and that is a sad tale of people trying to climb that mountain of piss. It always gobbles them up in the end. But yes, put it this way: I think any drinking song is a good song.”

We’re back in cartoon territory. But real life is never far away. Knight is glad the Cosmic Psychos are not a full-time concern. “The band is a hobby band because I could not be inspired or think about writing about anything if I was a full-time muso, because that would be as boring as shit,” he says.

“You’ve got to stub your toe. You’ve got to worry about being broke. You’ve got to get hangovers. You’ve got to get separated from your partner. You’ve got to have kids to worry about and all that kind of stuff. If you’re just travelling around in a fancy bus and flying around the world, what the hell are you supposed to write about?”