In 90s Italy, the ultimate seal of approval on a tape wasn’t that of a cutting-edge record label or a stickered quote from a tastemaker publication: it was the varsity-style, hand-printed banner that read “Mixed by Erry”. It adorned everything from regional rap records to collections of Gregorian chants and birdsong, and the fact that it was far from legal was no deterrent – not for customers, nor even the musicians that the lord of Italy’s pirate cassette business was ripping off.

Enrico Frattasio created the pirate mixtape label in the early 1980s, selling his tapes to illegal stallholders in his working-class neighbourhood in Naples, which they flogged alongside bootlegged cigarettes. By the late 80s, Erry had spread throughout Italy and beyond, to Romania and Hong Kong. At its peak, the Mixed by Erry group employed 100 people – including Enrico’s brothers, Claudio, Peppe and Angelo – with an annual gross of around £4m in today’s money.

Marco Messina, a member of 99 Posse, a Neapolitan band who dominated Italy’s hip-hop scene in the 1990s and 2000s, acknowledges that they owe part of their success to Mixed by Erry: “If I think of it as an individual, it’s money that they made from me and I haven’t earned. But in social terms, they have spread my music, allowing it to be better metabolised.”

In Italy, the brand gained a cult status and Erry a divisive reputation. Some see him as a criminal who got rich off the backs of artists; others as someone who brought good music to a wide audience. Now there’s a biopic about him, co-produced by Netflix.

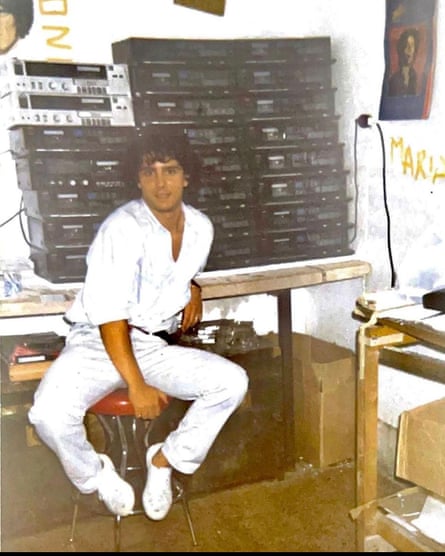

Born in Forcella, a working-class neighbourhood in Naples, Enrico was introduced to music as a byproduct of his father’s work in alcohol-smuggling: “I was 12 when my father sent me to be an apprentice in a record studio to keep me away from the wrong crowd” – the Camorra, drug dealers – he says today, speaking from Naples. “I came back passionate about music and started making mixtapes on demand.” He opened his first business at 17 after winning a small amount of money in a football bet: his first production was a remix of Ancora, a romantic hit by a Neapolitan singer Gennaro De Crescenzo with a French cover of the same song. Despite lacking the equipment to finesse the remix, it was so successful, Enrico recalls, that “people went to the Discoteca Meridionale, one of the largest record stores in Naples asking for the piece by De Crescenzo mixed by that guy from Forcella”.

Enrico started to professionalise his operation. When he issued a pirated copy of the compilation album Studio 54 – collecting tracks from the famous New York club, as mixed by Italian radio DJ Foxy John – Enrico adopted his business sobriquet and retitled the release Studio 54 Mixed by Erry. As it expanded, his brothers joined the business. The eldest, Peppe, became the manager, driven “by the need to put food on the table and by the birth of his daughter”, says Enrico. And it was Peppe who expanded the market beyond Naples, importing CDs and cassettes from Bulgaria and visiting expos in Asia to keep up to date with new technologies. “We were pushers of music,” says Peppe, speaking from Naples. “We used a quality product, we made a commitment, we listened to the tapes to see how the treble and bass were adjusted. We had an immense catalogue.”

“With the entrepreneurial experience of my brothers, we went from 50 copies to 300,000 of our great hits,” says Enrico.

More than just a copyist, Enrico was a tastemaker: at the end of one album, he might include two tracks by another artist that the listener might enjoy. “I was the YouTube or Spotify of the 1980s,” he said. “The money was not the point. I was building compilations. Each one took me a couple of days. I was doing a serious curator job.”

The Mixed by Erry brand became so famous that there were even imitations – pirated versions of pirated tapes. Erry was a kind of trademark, albeit an illegal one: the high quality of his productions was such that he branded his tapes as “false originals”, with a special stamp advising customers to buy only “original fakes”. “La cassette con fotocopie non sono Erry,” the covers read: “Cassettes with photocopied covers are not Erry”.

“Most of the other pirated tapes were of poor quality, including the ones pretending to be Mixed by Erry. Theirs used only good quality products,” says Neapolitan ethnomusicologist Simona Frasca, author of the book Mixed by Erry: La Storia dei Fratelli Frattasio. Frasca interviewed the Frattasios, beginning in 2019. She believes their story reflects the cultural and economic dynamics of southern Italy at the time: “Everything was completely illegal, but the law was tolerant because they solved the problem of unemployment.”

after newsletter promotion

Her theory reflects the brothers’ lived experience. “Where I lived, the whole neighbourhood lived on cigarette or whisky smuggling,” says Peppe. “It all seemed legal to us. If the police entered the shop and asked us what we were doing, we would answer: we’re making tapes.”

Messina of 99 Posse acknowledges, too, that “those who bought the cassette could hardly have afforded the original disc”.

Hence the Frattasios were able to carry on for years. “Occasionally authorities came and confiscated everything, but they had so many laboratories that the next day they started all over again,” says Frasca. Despite distributing their releases through the same network used by cigarette smugglers, Mixed by Erry became the third biggest record label in Italy, alongside the international giants RCA and Sony.

Eventually – inevitably – the climate shifted. With the advent of CDs, which cost more than tapes, the music industry pushed the Italian authorities to apply the law: in 1996, it proposed a bill introducing tougher punishments for piracy. (In the 90s, it also took a stricter approach to criminality in southern Italy.) In 1997 the Frattasio brothers were arrested after an investigation involving phone-tapping and undercover policemen. The Frattasio brothers and their father Pasquale were sentenced to four years, most of them served under house arrest.

It was the end of the Mixed by Erry era. But its legacy lives on. For many Italians, it was an opportunity to get to know international musicians for the first time: “I discovered Prince through Mixed by Erry,” says Frasca. For other artists, Mixed by Erry became a sort of a kingmaker. “Many singers, especially neomelodici – a quintessentially Neapolitan genre that happens to be popular with the mob – asked to be included in our compilations,” said Enrico.

The movie presents the Frattasio brothers neither as criminals nor heroes, but kids who loved music and ended up in over their heads. The real brothers seemed to like it: Enrico himself DJed at the movie’s premiere in Naples. “Erry, the legend is back to his passion,” wrote local newspaper Il Mattino.

Mixed by Erry still enjoys a fanbase. There is a Facebook group of enthusiasts; on eBay, an original Mixed by Erry compilation has been listed for €150. On Mixcloud, Italian DJ Renato de Vita runs a page where you can listen to old tapes, and another page with remixes by younger DJs who claim to have been inspired by him. “Erry wasn’t a DJ, he wasn’t a producer, he wasn’t a musician,” it says on the latter. “Erry was a superhero: like Zorro.”