In the late 1970s, Bo Goldman was researching a script about Melvin Dummar, the unassuming Utah factory worker, gas station owner and former “Milkman of the Month” who was named as a $156m beneficiary in a will supposedly written by Howard Hughes but later successfully contested in court. Slowly, a realisation dawned on the screenwriter: “This man is a failure just like I am.”

It seemed an unusual conclusion to reach. After all, Goldman had written the book and lyrics for a Broadway musical, First Impressions, based on Pride and Prejudice, before he was 30, and won his first best screenplay Oscar (shared with Lawrence Hauben) for adapting One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Ken Kesey’s novel set in a psychiatric institution, by the time he was 45.

A second Oscar later came his way for Melvin and Howard (1980), his humane and warmly funny script about Dummar, lovingly directed by Jonathan Demme.

But Goldman, who has died aged 90, was haunted at the time by his inability to sell one of his earliest scripts, Shoot the Moon, or to follow up that 1959 Broadway debut, and by the years he spent in poverty and debt, struggling to provide for his wife and their six children. “I can’t tell you what it does to a man,” he said in 1982. “You feel awful. I respected my wife so much, but felt lousy about myself.”

Hollywood was impressed by Shoot the Moon, the story of a brutal marital break-up that he wrote in the early 1970s, but no one wanted to make it. The writing was strong enough to earn him an $8,000 commission from the director Miloš Forman to re-write Hauben’s script for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. One of Goldman’s first suggestions – that the iconoclastic patient McMurphy, played by Jack Nicholson, should kiss his admitting officers at the hospital – helped win him the job.

He also scripted the Bette Midler vehicle The Rose (1979), inspired by the life of Janis Joplin, but turned down offers to write Kramer vs Kramer and Ordinary People, both future best picture Oscar winners, because the terrain felt too similar to his unproduced script, which he still hoped would be filmed eventually.

It finally was. The British filmmaker Alan Parker directed Shoot the Moon in 1982, coaxing powerful work from Albert Finney and Diane Keaton as the warring couple, and touchingly natural performances from the four children cast as their daughters.

The critical response was positive. Even Pauline Kael, no fan of Parker’s, said she was “a little afraid to say how good I think [the film] is” and praised the script’s “theatrical richness.” Goldman was disappointed nevertheless by its box-office failure.

After his third Oscar nomination, for Scent of a Woman (1992), he said: “I’m always surprised when anything good happens to me.” That film starred Al Pacino as a blind, cantankerous ex-army officer who cuts loose when he is assigned a prep-school student (Chris O’Donnell) as his companion for Thanksgiving weekend.

Goldman based Pacino’s character on a combination of his father, one of his brothers and a sergeant under whom he had served. Pacino won an Oscar; on that occasion, the writer did not.

He was born Robert Spencer Goldman in New York City. It was at Princeton that he changed his name to “Bo”; the college newspaper, The Daily Princetonian, misprinted his byline, and it stuck.

His mother was Lillian Levy, a millinery model, his father, Julian Goodman, a sometime Broadway producer and the owner of a chain of more than 70 department stores, which went into receivership during the Depression shortly before Bo was born. That dramatic fall informed and even overshadowed the rest of Bo’s life, with its occasionally incongruous juxtapositions. He grew up, for instance, in a spacious, rent-controlled Park Avenue apartment yet the family was usually penniless. His father would leaf through scrapbooks from his glory days, even making annual visits to the stables in Chantilly where he kept his prize-winning race-horses.

Though this precarious economic situation was known to Bo throughout his youth, it was not until much later that he discovered his father had another estranged family, and that his parents had never married.

He was educated at the Dalton school and Phillips Exeter academy prior to Princeton. There he wrote lyrics for the college’s Triangle Show and developed an enthusiasm for writing for the stage. He was in the US army for several years, then made inroads into the television industry, starting in the CBS postroom before progressing to script editing and producing on shows such as Playhouse 90.

Though First Impressions, which starred Farley Granger, was poorly received, he devoted most of the 1960s to writing a civil war musical, Hurrah Boys, Hurrah, which was never staged. He took odds and ends of TV work, but was plagued by thoughts of his father’s ignominies, and bruised by his own. “The only thing which kept me going was my wife and the kids who never cared about my success or lack of it,” he said. “They only cared because it was causing me pain.”

Around the time Shoot the Moon was released, his wife, Mab (nee Ashforth), whom he had met at Princeton and married in 1954, and who supported the family financially through endeavours such as her fish and bread shop, Loaves and Fishes, reflected on the disparity between the bad times and the good: “People were so contemptuous of us … it’s remarkable how success has transformed us into acceptable people.”

Goldman became a sought-after script doctor, working uncredited on Forman’s Ragtime (1981), Demme’s Swing Shift, the coming-of-age comedy The Flamingo Kid (both 1984), Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy (1990) and the Arthurian adventure First Knight (1995).

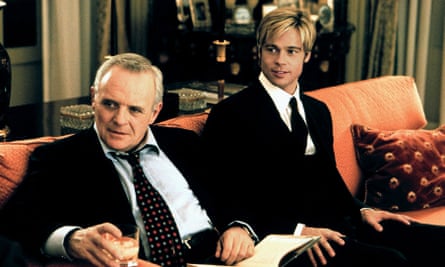

Credited screenplays include Little Nikita (1988), an espionage thriller with River Phoenix and Sidney Poitier, and Meet Joe Black (1998), starring Brad Pitt as the pretty personification of death. Goldman also shared a story credit with Beatty on the period comedy-drama Rules Don’t Apply (2016). This was another Howard Hughes-related project, with Beatty playing the reclusive billionaire.

Though Goldman came close several times, his enduring dream of directing was never realised. “I think of myself as a filmmaker,” he said. “I’m a writer only because that is what they pay me to do.”

Mab died in 2017. He is survived by five of his children, Mia, Amy, Diana, Serena and Justin. A sixth child, Jesse, died in 1981.