Every week we wrap up the must-reads from our coverage of the war in Ukraine, from news and features to analysis, visual guides and opinion.

Ukraine steps up counteroffensive

Ukrainian forces stepped up their counteroffensive after two months of gruelling, incremental gains, mounting a new push in the south of the country while edging closer to the fiercely contested eastern city of Bakhmut, Peter Beaumont reported.

The New York Times cited unnamed Pentagon officials as saying the “main thrust” of the counteroffensive had begun, with the Ukrainian army pouring thousands of western-trained and equipped reinforcements into a perceived weak spot in Russian defences in the Zaporizhzhia region. However, the Washington Post reported that a US official “expressed caution” in drawing conclusions that the main counteroffensive had begun: “We are seeing signs of preparatory moves for additional forces in the Zaporizhzhia area to come into the fight. But it’s not clear what the purpose of those moves may be.”

Earlier on Wednesday, Igor Konashenkov, the Russian defence ministry’s chief spokesperson, described a “massive” attack and fierce battles south of the settlement of Orikhiv, but said the attack had been repelled.

The US shared Russian war crimes evidence with The Hague

The Biden administration said it had begun sharing evidence with the international criminal court (ICC) in The Hague on war crimes committed in Ukraine, Julian Borger reported.

The announcement ended a months-long dispute in which the US national security council (NSC) and state department backed cooperation with the ICC, with the Pentagon resisting on the grounds it would imply endorsement of an international court that could one day seek to prosecute US soldiers.

The quiet decision to start sharing information about Russian war crimes with the ICC prosecutor, Karim Khan, suggests that Joe Biden has, after a delay of four months, taken a position in the debate.

Shock at Russian strike on Odesa cathedral

“Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy, Lord have mercy.” The priest dabbed tears from his eyes as his sonorous voice emerged from loudspeakers hastily assembled outside his devastated cathedral, the incantation competing with the crash of debris being loaded into trucks and the drilling of repair works on neighbouring buildings.

This was the second time that the vast, sand-yellow Transfiguration Cathedral, which sits in the heart of Odesa’s Unesco-listed historic centre, had been attacked, Shaun Walker wrote. In the 1930s, it was torn down during Joseph Stalin’s atheism drive. On Sunday morning, the rebuilt version was hit during a Russian airstrike. A missile blew a large hole in the roof, collapsed the altar and left several walls charred by fire.

It was one of several strikes on the southern port city in the early hours. Schools, residential buildings and a revered 19th-century mansion also suffered damage. One person was killed and 14 were hospitalised, the regional governor said.

Russian drones hit grain warehouses at Ukraine ports

Russian drones launched a four-hour attack on Ukraine’s Danube ports of Reni and Izmail, Peter Beaumont reported, destroying grain warehouses and other facilities, as Moscow appeared to escalate its attempts to strangle Kyiv’s globally important agricultural exports.

The attacks, using Iranian-supplied drones, followed Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea deal that allowed Ukraine to export its grain, and a threat by Moscow to target civilian carriers visiting Ukrainian ports – a threat that Ukraine later reciprocated.

Commenting on the attacks, the governor of Ukraine’s Odesa region, Oleh Kiper, told Ukrainian television: “Russia is trying to fully block the export of our grain and make the world starve.”

Inside Mykolaiv, where Russia destroyed the water supply

Ludmyla Osadchuk put her foot to the pedal and the rickety red-and-white tram edged forward, exiting the depot with a crunching of wheels and a rattle of the old, loosely fitting doors. On board were three blue canisters, each holding 1,000 litres of water.

With a “Special route” sign attached to the front window, the tram trundled to the first of four stops in different parts of Mykolaiv. The only passenger was former tram driver Serhiy Vytstyna, who hopped out at the stop and connected a set of pumps to the canisters.

The war has affected every city in Ukraine, but in each place the experience has been different. For Mykolaiv, a southern port city of nearly half a million inhabitants, which the Russians bombarded heavily at the start of the invasion but failed to occupy, a large part of the story has been about water. Shaun Walker had this story.

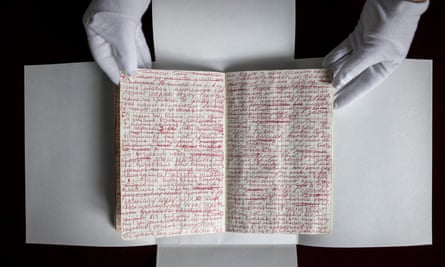

A murdered writer, his secret diary of the invasion of Ukraine – and the war crimes investigator determined to find it

When he realised the Russians were coming for him, Ukrainian writer Volodymyr Vakulenko buried his journal. Then he was taken away never to return.

Charlotte Higgins visited Vakulenko’s village and pieced together the story of the journal and the woman – Victoria Amelina – determined to find it.

Business brisk at Ukraine’s surrogacy clinics

In March last year, a few weeks after the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Remo and Amalia* received an unexpected phone call from Kyiv. One of the largest surrogacy clinics in Europe was responding to the Italian couple by inviting them to the war-ravaged country for medical checks to begin the procedure to have a baby.

At the time, Moscow’s troops were withdrawing from the territories north of the capital oblast that they had occupied for more than a month. A few days later, the mass graves of Bucha would reveal the true horror of the invasion as Russian missiles continued to fall by the dozens into Ukraine’s oblasts. Yet, the continuing conflict was not going to stop the couple.

Lorenzo Tondo and Artem Mazhulin reported that surrogacy clinics, which have thrived in Ukraine thanks to a liberal legal framework, are still doing brisk business, with hundreds of foreigners coming to Kyiv despite the war, mostly from Italy, Romania, Germany and Britain.

Couples who wish to have a child have to undergo a series of clinical examinations. Once these have been done, and if a doctor has diagnosed infertility, the couple starts the surrogacy process. After choosing a surrogate mother, appropriate agreements are reached between the parties.

How Ukraine’s pop and classical stars have taken up arms

Men arrive on crutches, two in wheelchairs, through a wintry dusk at the monumental neo-Renaissance opera house in Lviv, western Ukraine. About 100 seats tonight have been reserved for serving soldiers, who enter the lobby – a fin-de-siècle wonder – in military fatigues. They hand these in, so that the coat check looks like a barracks locker room. A contingent of 40 cadets from the city’s emergency firefighting department duly arrives, disarmingly young. For most, it’s a first night at the opera.

The occasion marks the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – a concert dedicated to the troops who have fallen during this first, monstrous year of war, and the innocent civilian lives lost. But also to The Invincible: a homage in music to Ukraine’s noble cause and just war. The programme is Bucha. Lacrimosa by Victoria Polevá, composed in commemoration of the victims of atrocities in that town during the early weeks of the war, followed by Giuseppe Verdi’s epic Messa da Requiem. The stage is blackened, and on each flank red roses are arranged so that petals fall towards the ground. Ed Vulliamy had this story.