“Mom, I want to go to Oregon.”

Jennifer Hesketh Aviles knew her daughter, Heather Thompson, wasn’t asking to finally visit Portland, or hike along the azure depths of Crater Lake. Heather wanted to go to Oregon for one reason: she wanted to die.

Oregon had legalized physician-assisted suicide for patients with a terminal illness (also known as medical aid in dying, or Maid) in 1997, and Heather, who had suffered with an intractable chronic illness for over 30 years, knew her illness was going to kill her.

“Death is coming for me,” Heather said. “It’s coming for me, Mom.”

Doctors had prophesied Heather’s potential mortality for years. “If you keep doing what you’re doing, you’ll end up in hospice,” said one. They meant it as a warning, but Heather remained impervious to the words. I’m fine, Mom, she reassured Jennifer.

Five years later, however, as her illness worsened, hospice sounded like a haven for her last days. But when the 48-year-old tried to find a hospice program in her native Tucson, she was rebuffed. Heather didn’t have a terminal illness, doctors said. Her condition was treatable. All she had to do was eat.

To her mom, this was laughable. Anorexia and bulimia had consumed Heather’s life since she was 15. She hadn’t been at a healthy weight for 33 years now, and still couldn’t bear the thought of eating normal meals and not vomiting them up. To quiet the illness’ perpetual hissing voice, Heather began abusing alcohol, opiates, and amphetamines just to get a few minutes of peace and quiet in her own head. Her temporary respite had become a crippling addiction. She spent years in institutions and group homes, bouncing from crisis to crisis. Nothing worked.

For years, all Jennifer wanted for her only daughter was recovery, or at least stabilization – anything better than the living hell in which Heather was trapped. Most of the doctors had long ago thrown up their hands at Heather’s case, claiming they couldn’t help her.

“If you can’t help her live, can you at least help her in death?” Jennifer begged them.

More than 18,400 scientific research articles on anorexia nervosa are listed in the National Library of Medicine, many of which begin with a similar sentence: anorexia nervosa is the deadliest psychiatric disorder. As many as one-fifth of people with chronic anorexia die as a result of their illness, a mortality ratio that only opioid use disorder competes with. It’s a statistic that hasn’t budged in half a century.

Yet despite this vast research literature, the doctors treating Heather had no guidance on when to allow a patient to stop treatment and if the disorder could, in fact, be considered terminal.

Jennifer Gaudiani, one of the country’s only physicians specializing in the treatment of medical complications of eating disorders, couldn’t find anything, either, when she cared for a series of three individuals who had decided – with Gaudiani’s and their family’s agreement – to allow their self-starvation to take its ultimate, fatal course.

She ended up co-authoring an article, published in February 2022 in the Journal of Eating Disorders, about what she dubbed “terminal anorexia nervosa”. It was intended as a guide for physicians like herself, to help them care for their desperately ill patients. One of those options included Maid, which is legal in 10 states and in Washington, DC.

The article sparked a firestorm in the medical community.

“It was both uncomfortable and painful to receive often pointed condemnation from colleagues that I respected and from some patients,” she says. “But my discomfort is far less than the actual discomfort of the people for whom this article was written.”

The issues Gaudiani raised have an obvious impact for the millions of Americans struggling with anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder. But it goes deeper than just eating disorders. To define terminal anorexia – to decide whether it should be defined at all – requires society to grapple with crucial questions about the nature of refusal of treatment, how an ostensibly treatable illness can be considered terminal, and, most fundamentally, the bodily autonomy of psychiatric patients and their capacity to decide when enough is enough.

Millions of years of evolution have given the human body the capacity to withstand prolonged starvation and dehydration. The body can cope, right up until the moment it can’t. As a result, many with eating disorders can be at high risk for sudden death even as their blood work appears normal.

The strain of starvation, binge eating, and purging can cause the heart to abruptly stop. Some, seeing no escape from a disorder that won’t give them a moment of nutrition, rest, or peace, take their own lives. These deaths are sudden and often unexpected. Other deaths are slower. As the body runs out of energy to perform even the most basic functions, organs simply shut down. It often takes years, even decades, to get to this point of no return.

It’s something Gaudiani knows all too well. The internist didn’t set out to care for those with eating disorders, but when she learned of an opportunity to head up a new, hospital-based unit in Colorado to treat the severe medical complications of these disorders, she signed up for the challenge. It became her calling.

As the medical director at the Acute Center in Denver, which specializes in the treatment of severe eating disorders, she watched as the tinctures of nutrition, medication, compassion and time, alongside her patients’ determination, worked to help bring them back from the brink of death. Fears of food and weight gain, however, were deeply ingrained, and many patients tried to bolt.

In some cases, Gaudiani knew her patients’ illness had taken over their decisions. They had blood sugar readings in the 20s (below 50 can be deadly), potassium levels that could stop their hearts at any second, and yet insisted they didn’t need to eat and would be fine. Because these patients were unable to grasp the consequences of their actions, Gaudiani felt they were not competent to make decisions about their own health.

Other times, however, patients knew exactly what the outcome of their actions would be. Not long after she began at Acute, Gaudiani began to treat a patient who said she was done with treatment and didn’t want to go back into the hospital. The patient knew if she allowed her malnutrition to continue, she would die. But she had tried a variety of programs at hospitals around the country, and nothing helped. Her primary care physician fired her, saying she was too high-risk, but hospice disagreed that her condition was terminal. After several long conversations with her patient, Gaudiani agreed that more of the same wouldn’t help.

“We cannot de facto say that because somebody with a starved brain and anorexia nervosa is making a choice that some clinicians disagree with that they lack capacity,” she says. “It disrespects the fundamental capacity of some individuals with severe mental illness to make decisions for their own bodies.”

Gaudiani searched for guidance from other eating disorder experts and bioethicists. She found nothing in the research literature, and no one would chime in. Gaudiani was on her own. The young patient wanted to go home and let her anorexia run its course. Gaudiani thought she had, at most, days to live. Which was why she was so shocked when her patient called several weeks later, still alive, despite having the weight of an average four-year-old. Her patient’s body hung on for another month before finally succumbing to malnutrition.

The experience haunted Gaudiani throughout her tenure at Acute, and when she transitioned to private practice in 2016.

“I still cannot speak of this story without tearing up. It was a terrible death for her and her parents,” Gaudiani says.

She vowed she would never let a patient die alone on their couch again. More than a decade later, in 2019, she faced a similar situation with a 34-year-old man who had battled anorexia for 18 years. The previous decade of medical literature hadn’t added any guidance for physicians. This time, however, Gaudiani found a kindred spirit in the New Mexico psychiatrist Joel Yager, who established the first dedicated eating disorders unit at the University of California, Los Angeles, and had spent 40 years treating adults whose eating disorders did not respond to current treatments. He believed that forcing a patient to keep enduring ineffective treatment was tantamount to torture. Yager’s presence was crucial in helping Gaudiani navigate these stormy waters.

Not long after the young man died, Gaudiani faced the problem again, this time with two patients at the same time. Both lived in states where Maid was legal, and Gaudiani said her professional ethics required her to give her patients this option. Both agreed, although one died of malnutrition before she took the prescribed medication to end her life. The other took the medication and died peacefully, surrounded by family.

While Gaudiani’s expertise on anorexia was second to none, she knew that most people with eating disorders were being treated by physicians who had only heard a single lecture on the subject in medical school, if at all. These patients needed help, too. So Gaudiani and Yager decided to write the paper, which would summarize what she had learned about terminal anorexia. One of Gaudiani’s patients, Alyssa, was so passionate about the subject that she asked to be a posthumous co-author.

In the paper, Gaudiani, Yager, and Alyssa proposed a set of criteria for terminal anorexia: being at least 30 years of age, having engaged in “high-quality, multidisciplinary eating disorder care”, and consistently and clearly expressing that they understand continued treatment is futile and that they will die from their disorder.

When the trio published the paper, Gaudiani braced herself for controversy, but nothing prepared her for the intensity of the blowback.

Just eat.

This simple commandment has been the cornerstone of anorexia treatment since the English physician Sir William Gull and the French doctor Charles Lasègue first defined anorexia nervosa in western medical literature in 1873. In a world burgeoning with multimillion-dollar gene therapies, the idea of serving up three square meals each day to cure a life-threatening disease seems too good to be true. And to some extent, it is.

From the start, Gull wrote at length about the “willful obstinacy” of the young women he treated. The only cure was food and rest, to be delivered by those with “moral authority” over the person. “The inclination of the patient must be in no way consulted,” Gull writes, since left to their own devices, those with anorexia could – and sometimes would – starve themselves to death.

Especially when the illness begins, those with anorexia feel that continuing weight loss is exactly what they sought. Far from being a problem, it’s a goal to achieve. Even as anorexia tightens its grip, many of those with the condition continue to assert that nothing is wrong. This, coupled with the deep-seated fear of eating and weight gain, means that many with anorexia don’t seek treatment. When they do, they are often ambivalent about recovery, and they can be hostile towards clinicians and the idea of weight gain.

For decades, doctors tried any range of tonics and tinctures to help, including hormone therapy and electroshock. Freud himself posited the disorder resulted from a fear that eating would result in pregnancy and recommended psychoanalysis. Nothing helped. With no effective therapies, blame for anorexia’s chronicity fell on the patients, who gained a reputation for being devious and manipulative.

Treatment has changed little in the past 150 years. Especially for the most severely malnourished, the focus remains on refeeding (which can have potentially deadly side effects if performed too quickly), and normalizing vital signs and blood chemistry. Other damage caused by the disorder is less obvious but no less concerning. Heart rate and blood pressure drop and digestion slows as the body literally eats itself alive for energy. MRI scans of people with anorexia reveal a brain that has shrunk dramatically, as a lack of nutrition harms neurons and the connections between them. Even relatively short periods of starvation destroy bone mass, leaving 20-year-olds with the brittle bones of an octogenarian.

With the exception of bone density loss, nearly all of these issues are reversible with time and renourishment, says Phil Mehler, co-founder and CEO of Acute.

“The body isn’t broken. The heart isn’t broken. They’re sick, but they’re not irreparably broken. There’s no body system that is,” he says. That’s why he remains staunchly opposed to the idea of terminal anorexia and the use of Maid.

Knowledge of the devastation that anorexia inflicts on the body and mind isn’t always enough to spur someone to abandon their disordered behaviors. Cushla McKinney says that, thanks to her PhD in biochemistry, she knew the effects of her disorder down to the molecular level. Yet she felt powerless against the demands of anorexia to exercise more and eat less. She was hospitalized numerous times in her native New Zealand, where even basic creature comforts, such as showers and visits with family, had to be “earned” by gaining weight. McKinney ate her way out of hospital, only to return to her anorexic ways upon release.

“I had given up on myself,” she says. “It’s incredibly painful to spend your entire life starving and exhausted and freezing and stuck in a pattern of compulsive behavior that you just can’t get out of. I just got to a point where I didn’t think I could do this any more, that it’s not going to get any better, and nothing will make a difference.”

Up to 70% of those hospitalized for anorexia will relapse after discharge, according to some studies. In another study, nearly four in 10 of patients needed at least one re-admission, just like Cushla did, although she eventually recovered in her 30s. Many will return, again and again.

It’s a hallmark of those with severe forms of the illness, says Angela Guarda, director of the eating disorders program at Johns Hopkins Medicine, who treated McKinney when she was hospitalized while a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland. Several studies have shown that the higher a care team can nudge a person’s weight during intensive treatment, the less likely they are to relapse.

Weight restoration, in and of itself, is only one part of anorexia recovery. What takes far longer, and is more challenging, is helping those with anorexia maintain their gains, and also address the anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, trauma, and crippling perfectionism that often accompany the disorder. “I’ve treated thousands of patients. Not everyone reaches target weight and suddenly has a lightbulb go off. It’s a more gradual process,” Guarda says.

Not surprisingly, the course of illness tends to be protracted. A 1997 study of teenagers hospitalized at UCLA showed it took, on average, seven years for weight, eating patterns, and body image to fully recover. Some people never make it to that point. An oft-cited 2002 article created what’s been nicknamed the rule of thirds: one-third of those with anorexia recover completely, one-third improve, and one-third remain chronically ill or die.

Just as importantly, studies have found that the likelihood of recovery hadn’t changed over the past 50 years. The mortality rate of chronic anorexia has been pegged as high as 20%. While many succumb to the physiological effects of starvation, a substantial proportion of people with anorexia take their own lives. Compared with similarly aged peers, women with anorexia were 56.9 times more likely to die by suicide, according to another study.

Despite the grim statistics, Mehler says he has seen “miracles” occur, even in the sickest of the sick who have been life-flighted to Denver with a BMI in the single digits and entering multi-organ failure.

“A woman will be airlifted to us tomorrow morning at 6am from the east coast. I’d say that she has a 98% chance of living,” Mehler says.

But these miracles require someone to consent to treatment, and not everyone does.

Many mothers weep when they see their daughters in their bridal gowns. Linda Mazur choked up at Emilee’s beauty, yes, but tears also sprang from her shock and horror at just how much weight her 25-year-old daughter had lost in recent months.

“We were aware that something was off, but she wouldn’t admit what it was,” Linda recalls.

Only months later would she learn that Emilee, then 25, was not only starving herself but also abusing laxatives. But she shrugged off her parents’ concerns, attributing the weight loss to the stress of the wedding and graduate school.

Linda held her breath and waited for her daughter to reverse the downward trend. If anything, it accelerated. Emilee reluctantly agreed to see a therapist for her anxiety and depression, but continued to insist her eating wasn’t a problem.

When she could no longer deny her ongoing weight loss, Emilee insisted she could handle the problem on her own. Powerless to do anything besides encourage their daughter to seek more help, Linda and her husband, Jack, watched as anorexia deepened its hold on Emilee.

After several years and the dissolution of her marriage, Emilee reluctantly agreed to seek specialized treatment. But when she gained two pounds in six days, her insurance kicked her out. Emilee now weighed more than 75% of her ideal body weight, which meant insurance deemed hospital-based care no longer medically necessary.

It confirmed what the eating disorder was whispering to Emilee: that she was too fat for treatment, and didn’t deserve help. She returned home to Rochester, New York, where she vowed never to be humiliated in such a way again. It didn’t take long for her to return to laxative abuse. Not long after, she began drinking heavily and lost her job as a pharmacist.

Even if Emilee had agreed to return to treatment, Linda says she didn’t know if any treatment centers would take her. Eating disorder facilities told Linda they couldn’t treat her because of her severe alcohol abuse. Drug rehabs refused her due to her eating disorder. She was too medically compromised for a psychiatric unit, but her anorexia symptoms were too challenging for a general medical ward. And while Rochester had hospital-based eating disorder programs for teens, they didn’t treat adults like Emilee.

Battered by starvation and booze, Emilee became a frequent flyer at the local emergency department. She would stay long enough to receive IV fluids and other treatments to keep her from dying immediately, just to return home and begin the cycle anew.

Terrified of Emilee’s downward trajectory, Linda and Jack asked whether their daughter might be treated involuntarily. This would require a psychiatrist and judge to declare that she lacked the mental capacity to refuse care. Since Emilee appeared outwardly rational and seemed to comprehend the consequences of her decision, however, psychiatrists repeatedly ruled her competent to refuse treatment, despite her life-threateningly low body weight and alcoholism. So Emilee discharged herself and the cycle continued.

“It should have never got to that point, because she wasn’t competent to make all those decisions,” Linda says.

Stephen Touyz, a psychiatrist at the University of Sydney who has treated anorexia patients for 30 years, had seen plenty of patients like Emilee. Available treatments fell short, and all Touyz could offer was more of the same.

“We have nothing else to give but the same treatment that’s failed. That’s unacceptable to me,” Touyz said.

He believed that Emilee and people like her – with what he called severe and enduring anorexia nervosa – needed and deserved something better. But how do you test the efficacy of a treatment for those who are disillusioned with medicine and drop out of trials at alarmingly high rates?

Touyz did it by not requiring any weight gain. The goal of his therapy was to improve quality of life. Patients had to commit to not losing more weight, and though he said he would move heaven and earth to help them gain it if they wished, that was not the goal. He took out full-page advertisements in local newspapers in Sydney and London, and waited.

Almost immediately, the phone began to ring. It didn’t take Touyz long to recruit 63 people for his trial, in Sydney, Melbourne, and London. His study, published in 2013, compared cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; often used to treat anorexia, but Touyz removed the parts of the treatment that pushed weight gain) with general supportive care.

In both treatment arms, Touyz found, his patients’ quality of life improved significantly, even in the absence of weight gain. Two patients improved to the point where they were able to become pregnant and start families. To eating disorder professionals, who had long since thrown up their hands in despair, Touyz proved that it was possible to treat those with long-term anorexia. A 2017 study that followed people diagnosed with anorexia and bulimia for an average of 22 years supports Touyz’s approach. The work there found that only one-third of those with anorexia recovered after 10 years, but that rate doubled after another decade.

“Never lose hope,” he says. “Some patients are ill for 10, 15, 20 years and they still recover.”

But even Touyz himself admits that, for his approach to work, patients need to find some sort of balance between a weight that is at least minimally tolerable and the life they want to live.

Not everyone, however, can find this kind of balance. Their illness is just too severe, too relentless to carve out even a fragile detente. For them, Touyz says, hospice care may be the only option that can alleviate their suffering.

When Heather first got sick at 15, Jennifer believed her daughter’s stubbornness would eventually evict anorexia and bulimia from her life. Instead, it was Heather’s stubbornness – reflected in her fiery green eyes and jaw-length hair dyed raven black – that kept her disorders fully entrenched.

As the decades passed and her daughter’s illness intensified, Jennifer began to shift her hopes away from full recovery to just keeping her daughter alive. The years of profound malnutrition coupled with addiction, however, soon made staying alive all but impossible. The irony, Jennifer says, is that for all the times Heather was threatened with hospice, she couldn’t actually find a hospice team when death began to seem almost inevitable in 2019. Doctors only offered more of the same treatments that had failed before.

Instead, the emergency room became Heather’s second home. The doctors and nurses knew Heather by sight and had little compassion for her. “They figured, why are we wasting resources on this woman when there are other people who are willing to fight?” Jennifer said.

As the Delta variant of Covid-19 began its global surge, Heather began to develop bedsores. To Heather, these provided a pathway to death for her weakened, wasted body that continued to survive a ruthless eating disorder and addiction. She hid them from nurses and refused antibiotics when they invariably became infected. Finally, weakened and septic, Heather relented and called 911, and she was rushed to the hospital. Physicians cut away the dead, infected tissue to allow the wounds to heal, which only worsened Heather’s pain.

“Morphine! Give me morphine!” Her shrieks of agony echoed through the hospital’s sterile halls. They were some of the last words Jennifer heard her daughter speak.

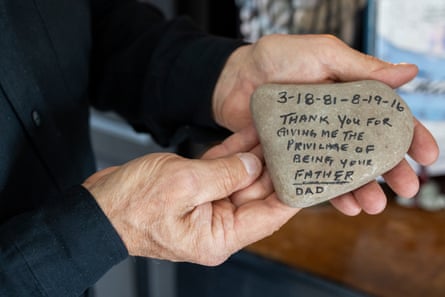

Less than 24 hours later, Heather developed pneumonia and was admitted to the ICU for a ventilator. The ICU team gathered Jennifer, Heather’s stepfather, and her father for a conference. If Heather’s heart stopped, CPR would cause catastrophic damage to her ribcage. Her prognosis was grim, and her doctor recommended comfort care. Everyone agreed to remove life support, and on 2 October 2021, Heather took her last breath.

The next day, Jennifer posted the following message on Facebook: “So, yes, do say her name. Heather Thompson. Our beloved daughter passed away peacefully early yesterday evening after an unbelievably difficult two weeks during which she fought a serious infection and pneumonia and more than 30 years an entrenched eating disorder and co-occurring illnesses. She is in such a better place now with God and among the Angels.”

When Gaudiani and Yager’s paper on terminal anorexia was published in February 2022, Jennifer’s grief remained fresh and raw. Reading the article, however, provided a balm. Maybe if more doctors understood the grim reality of what it meant to die from anorexia, fewer mothers would have to watch their daughter’s agonizing death throes, Jennifer says.

But the quiet support of Jennifer and other parents who had lost their children to anorexia and bulimia was drowned out by more vocal objections. Within days of the paper publishing, the conservative columnist Wesley Smith wrote in the National Review that “allowing assisted suicide for psychiatric illnesses would open the door wide for medicalized killing”.

Guarda, of Johns Hopkins, and Mehler, of the Acute Center, had more specific concerns, arguing that terminal anorexia was a “dangerous term that cannot, and should not, be defined”. Both had seen patients return from the brink of death and build meaningful, happy lives. Guarda also says that she is unable to predict exactly which patients will do well, and who will remain severely ill. Her fear is a patient with the potential for recovery getting labeled as terminal.

More than that, she worries that patients will label themselves as terminal and give up all hope – something she witnessed not long after Gaudiani’s paper was published.

“When they’re in the depths of the illness, often patients cannot imagine that they can live without their anorexia,” Guarda says. “In most cases, I just assume people have the capacity to get better because I’ve been proved wrong too many times.”

McKinney echoes that fear. After months of treatment at Johns Hopkins, she has returned to New Zealand, where she works as a PhD scientist and lives with her husband and children – things she never felt were possible when in the throes of anorexia. “By that stage, I was so tired and so hopeless, that I think I would have chosen [hospice],” she says. When asked if she was glad that hospice hadn’t been an option, she doesn’t hesitate to answer yes.

To Mehler and his colleague Patricia Westmoreland, a forensic psychiatrist who works with Mehler to assess anorexia patients for capacity to refuse treatment, a major issue is how starvation impacts the brain. He cites the brain shrinkage studies and points out how resistance to treatment and weight gain are defining characteristics of anorexia. Calling the illness “terminal”, even in just a few patients, risks colluding with their eating disorder. “It’s going to have a contagion effect. Everybody’s going to give up and say ‘I have terminal anorexia, just put me in hospice,’” Mehler says.

Gaudiani disagrees entirely.

“Anybody with an eating disorder remembers the hopelessness, the many days where they thought they just don’t want to be alive,” Gaudiani says. “There is a difference between hopelessness, wishing that you didn’t have to deal with life any more, wishing you were dead, and making the choice, ‘I’m entering hospice. I am progressing towards my death without anything interfering.’ There is a major difference between those.”

Still, the differences between how Guarda, Mehler, and Gaudiani would treat someone with a severe, decades-long eating disorder who has been consistently failed by existing treatments aren’t as different as their positions would suggest. All three have, on occasion, referred patients to hospice and have begun turning to so-called harm reduction approaches, which focus on reducing behaviors rather than eliminating them entirely, especially for those who cannot recover fully, even after trying for decades.

The difference between them is Gaudiani’s creation and use of a category called terminal anorexia, and her openness to Maid. However, she remains steadfast that she wants to help her patients. “This is not giving up on patients. This is not giving up on patients who suffer for a long time. This is not thinking that recovery isn’t potentially possible. It’s none of those things,” Gaudiani says. Acknowledging that some patients don’t survive their illness and might need the support of Maid or hospice doesn’t detract from someone’s capacity to fully recover from their disorder, she argues.

Despite Guarda’s and Mehler’s arguments to the contrary, Jennifer and the Mazurs say that a definition of terminal anorexia is exactly what the field needs. After witnessing Emilee’s steady, inexorable deterioration even after her treatment at Acute, her parents, too, tried to help Emilee find hospice care. Like Heather, they were rebuffed.

But after another admission at a different hospital, they found a palliative care physician who diagnosed Emilee with “terminal recalcitrant anorexia nervosa”, and agreed to treat her in hospice. Jack Mazur wept at the diagnosis – not just out of grief, but out of relief that someone was taking his daughter’s anorexia seriously.

“Nobody wanted to deal with it,” he says.

Emilee’s last days were spent peacefully in a dedicated hospice home, where she breathed her last with her loving parents looking on.

When asked about the physicians who said terminal anorexia wasn’t a real diagnosis, Jack’s voice shook with uncharacteristic rage. “For people to read that article by Dr Gaudiani and call her Dr Death is just … I was so angry when I saw that,” Jack says.

Gaudiani isn’t surprised that families who have experienced the agony of watching their child die support the idea of terminal anorexia. These cases, she says, are thankfully rare, but these individuals are no less deserving of the compassion and care given to those on the path to recovery.

“Even as I respect people’s rights to dissent, I’m also not going to back down,” she says. “I know for a fact that this advocacy is correct and that these individuals deserve to be cared for compassionately at the end of their lives.”