One day in 1978, Janine Wiedel found hell a few streets south of Spaghetti Junction in Birmingham. “The noise was deafening. The heat was intense. I’d never seen anything like it,” she says. In her native US, she’d photographed Black Panthers and student protests at Berkeley in California, but neither prepared her for this industrial inferno, on which one-time West Midlands resident JRR Tolkien reputedly based Mordor.

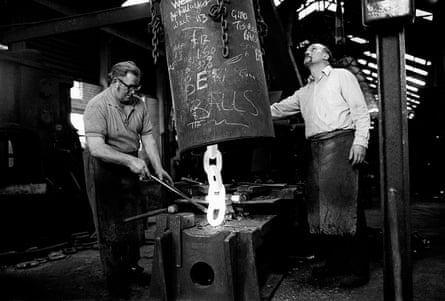

Inside Smiths’ Drop Forgings were nine 35-hundredweight hammers worked by some of the filthiest men she’d ever seen. The forge had been in operation since 1910 and was typical of the small Birmingham firms that made the city proudly define itself not just as the workshop of the world but as the city of a thousand trades.

This particular forge made couplings for British articulated lorries. A piece of metal was heated in a furnace, then placed beneath one of the hammers. One of Wiedel’s portraits depicts Alan, the stamper, releasing the rope that dropped the hammer about nine feet with an ear-splitting smack. No wonder heavy metal originated in the West Midlands: Ozzy Osbourne and Tony Iommi, who lived a few streets away, probably heard these hammers before they formed Black Sabbath.

Wiedel recalls that the hammers were referred to as Jim’s or Bob’s or Alan’s. “They belonged to the men, which showed how close they felt to their work. I remember they used to say, ‘Any child could work in the modern forges, but we are the real stampers.’ There was a pride and a camaraderie I suspect you don’t find much nowadays.”

That pride is evident in her photographs. “I don’t think there was one person who said they didn’t want to be photographed. They were just pleased, I think, by the fact that someone was taking an interest in their jobs.”

The New York-born photographer was in Birmingham thanks to a bursary from West Midlands Arts, which wanted her to document the local people. She was making a name for herself as a documentary photographer who spent time earning the trust of the close-knit, often threatened communities she photographed, such as the Inuit of Baffin Island in Canada and Travellers of western Ireland.

Her West Midlands project was trickier because she decided to document a diverse range of communities – the miners of North Staffordshire, the chainmakers of Cradley Heath, the metal stampers of Aston, the potters of Stoke, the blastfurnace workers of Bilston, the craftspeople of Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter. The results of the project are due to appear in a book called Vulcan’s Forge.

In it, she documents ways of living and working that had existed in the Midlands for centuries. Some details also date-stamp her work: one chap in a woolly hat has a safety pin attached to his earring – this was the era of punk rock.

What Wiedel didn’t realise was that she was documenting end times. Many of the industries she photographed no longer exist: the steelworks and blast furnaces of Bilston closed before the 1970s were out. The colliery in Sedgley has become a country park, as if Mordor had mutated into Hobbiton. Today, Cradley Heath still makes chains, and there are artisans in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, but many fewer are employed in these trades than when Wiedel first visited. “It was the late 1970s, a time of economic crisis and underinvestment,” she recalls.

The coup de grace for many firms came after the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979; her chancellor of the exchequer Geoffrey Howe’s deflationary budgets sped up the region’s deindustrialisation. The later defeat of the miners’ strike effectively closed collieries like the Staffordshire one Wiedel photographed.

The photographer would travel the region in a VW camper van, in which she also lived. Each night she would develop her film to see what she had captured, like a movie director studying the day’s rushes. At weekends she’d return home to London and print her favourite pictures. Though she strove to spend time with her subjects to get beneath the cliches, the task was made trickier when an ATV film crew, fascinated by this American’s interest in heavy industry, shadowed her for a documentary on the project.

She capturedwhat now seems like a health and safety nightmare. In nearly every photograph from Smiths’ Drop Forgings, cigarettes dangle from workers’ lips as they work surrounded by raging flames and molten metal. “There were lots of accidents,” recalls Wiedel. One group shot shows a man with a plaster across his nose next to another with a fresh cheek wound.

Several of her most charming images are of men from the forge quenching their thirsts at lunchtime with well-deserved pints. Were these men really going back to operate heavy machinery afterwards? They were. “Wouldn’t be allowed today, of course.”

In one shot, which she called Waiting for Dad, a little boy weighed down by his school bag stands outside the mighty forge. That boy grew up to become Andy Conway, the prolific novelist and screenwriter. One of his Touchstone sequence of novels, Fade to Grey, is set in the forge and includes a nod to Wiedel’s project, which he praises for documenting a fast-disappearing working-class world in all its toil, squalor and occasional majesty.

One of Wiedel’s heroes is Dorothea Lange, famous for her US Depression-era photographs. Vulcan Forge has Lange-like integrity and evident fondness for the people she depicts. But Wiedel’s West Midlands project reminds me most of the work of another American, Janet Mendelsohn. When she was a Birmingham University photography student in the 1960s, Mendelsohn made a celebrated study of Varna Road in Balsall Heath, then a red-light district described as ‘The wickedest road in Britain’.

Both Wiedel and Mendelsohn shot in black and white; both achieved a non-judgmental intimacy with their subjects. But Wiedel went where women rarely trod. At Littleton Colliery, north of Cannock, Wiedelthinks she was the first woman allowed to descend to the coal face. “The miners were reluctant to let me go down the pit. They said: ‘You haven’t got the right footwear,’ which was nonsense. There was a prevailing idea that it wasn’t good luck to take a woman down the pit shaft.

“In the end they gave me a helmet and said, ‘Follow us’. I trotted after them with my tripod, but it was a nightmare. It was absolutely black and I couldn’t use flash. I managed to use the helmet light and paint the light that way.”

Away from the pit, many women did of course work in the industries. Some of the most compelling pictures in Vulcan’s Forge are of women making chains in Cradley Heath and gilding medals in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter. “There was one woman, Florence Allen, who had the secret formula for gilding. Everybody was terrified that when she died she would take it with her.”

After her West Midlands project, Wiedel spent two years in the early 1980s with women anti-nuclear protesters at Greenham Common. She doubts my thought that she was going from a tough man’s world to a sympathetic women’s one. “For me, both communities were fighting for a certain lifestyle. When I look back on my work I think I’ve always been drawn to people who have the strength to survive despite the pressures of society. I often take pictures of people who protest and I’m interested in what it takes to get people out on the streets to stand up for things they really believe in.” That’s what impelled her to photograph the Black Panthers in the 1960s and what has inspired her most recent work, documenting Black Lives Matter protests and Iranian female demonstrators. “These people are fighting for their own identities. That never ceases to impress me.”

Last year, Wiedel went back to Birmingham for an exhibition of the pictures she’d taken 45 years earlier. “The best thing was that so many of the men I’d photographed back then showed up, older, greyer but still lovely.” During the intervening years, she has regularly been asked for photographs by family members. Only the other week, a family got in touch with her after their dad, whom she photographed, had died – they wanted one of her pictures of him at work for the funeral service booklet. “I was really pleased to be asked to do that because there is so little documentation of what it was like to work in these industries – so little for their kids and grandkids to see, to give them an insight into what their dad did.”

What she recorded is a time very different from our image-saturated 2023. “For many of these people this would have been the first time they had been photographed at work. There were no mobile phones, no selfies.”

Often the portraits she produced were a shock to the men’s families. “I remember one woman saying to me, ‘Couldn’t you have got him to wear a suit?’ In those days, you might be photographed at your wedding and that was about it. Women didn’t know what their men looked like at work because they’d never been inside the forge or down the pit.

“It was important to record these lives,” she concludes. “For me, it’s been great to give people back their history – that’s the best part of what I do.”